Cubitt’s Brick & Cement Company

Cubitt’s Brick & Cement Company

This page is an early draft and is in the process of being updated. There is substantial new material to add.

Whilst this page started out as the story of Thomas Cubitt and his Burham Works it progressively became clearer, as further materials were located, that it was also a story that we well covered from the Cubitt & Co wet letter books. So it was decided to fully utilise the surviving materials until the end of Cubitts [the company’s] involvement in the Burham Works.

This page is also highly illustrative of the extent of the efforts that have been made to gather highly scattered and fragmentary materials from London Archives, Kent Archive, Medway Archives, Church of England Archives, Diocese of Rochester and a good few other archives together in order to produce a coherent account of the development of the works.

This page has benefited from contributions from and discussion with; Stephen Weeks; Dylan Moore; members of The Industrial Locomotive Society; members of the Industrial Railway Society both of whose members had previously studied the development of the rail layouts of the works who kindly provided reprints and many others.

In trying to better understand Cubitt, the man, it seemed essential to try and retrieve as much data on one of the final main parts of Thomas Cubitt’s working life. It turned out that a lot of other researchers had looked at the Burham Works but had been defeated by the dearth of a single archival source or much in any archive anywhere for that matter and the sheer complexity and contradictory nature of some of the surviving records. It then became a painful process of peacing together small scraps of information from multitudinous sources; placing them in date order by theme and then trying to extract information from them.

Without the help, in tracking down missing archival materials, from people within the industry this page would not have been possible. Hopefully it will prove possible to place the materials recovered in a properly accessible archival setting for future researchers.

This page would have been simply impossible without the kind assistant of Tim Warrender of London Archives conservation team who patiently enabled access to Thomas Cubitt’s surviving letter books.

Introduction

It was quite normal for major contractors to lease or own their own brickworks. Indeed anything heavy tended to be made quite locally as the difficulties of transporting heavy goods via horse and cart are quite clear.

This started to change in the canal and even more so in the early railway eras, when private sidings for yards and even for large projects were not uncommon.

Cement works were a novelty in the 1850’s as cement only became common in the 1840s amid much, often justified, suspicion as to manufacturing quality.

This page is split into the following sections

- General Background

- Brick making in the 1850s and prior

- Why Burham

- Acquisition of the various parcels of land and existing works

- Earl of Aylesford

- Church Commissioners

- The Sir Edmund Gregory Charity

- The elusive Mrs Smith – who owned the lands of the chalk pits

- Cubitt’s Setting up of the Burham Works

- Brick making

- Cement making

- Tile making

- Lime Burning

- The Post Thomas Cubitt History of the Works

- 1859 – Abortive sale to The Burham Brick, Pottery & Cement Company

- 1860 – The transfer of the Brickworks to Smeed and Prall

- 1860 – possible leased/operated by Webster & Co

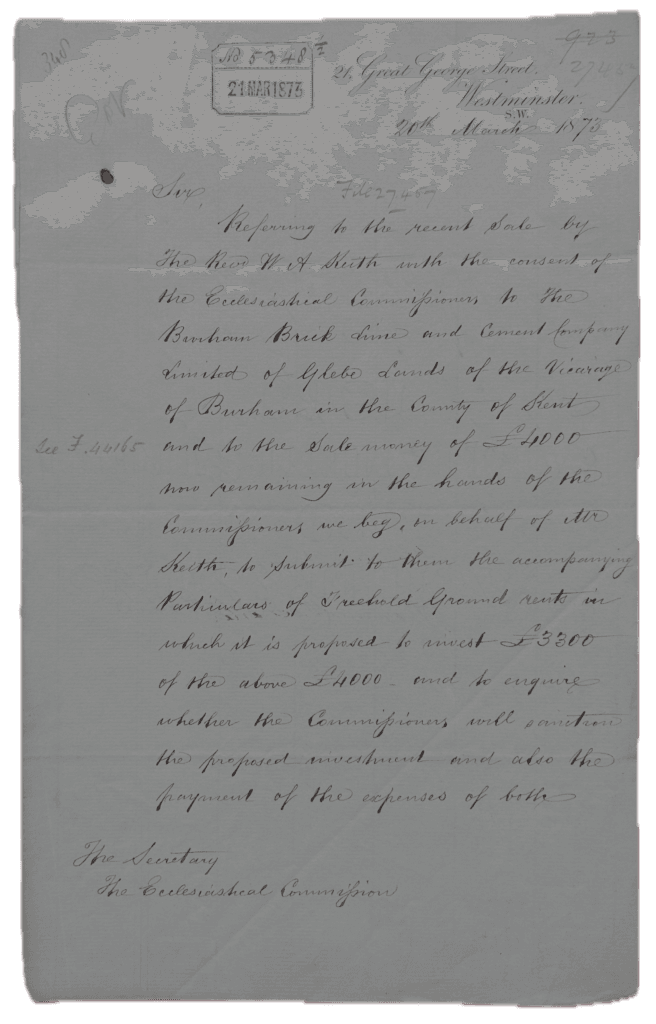

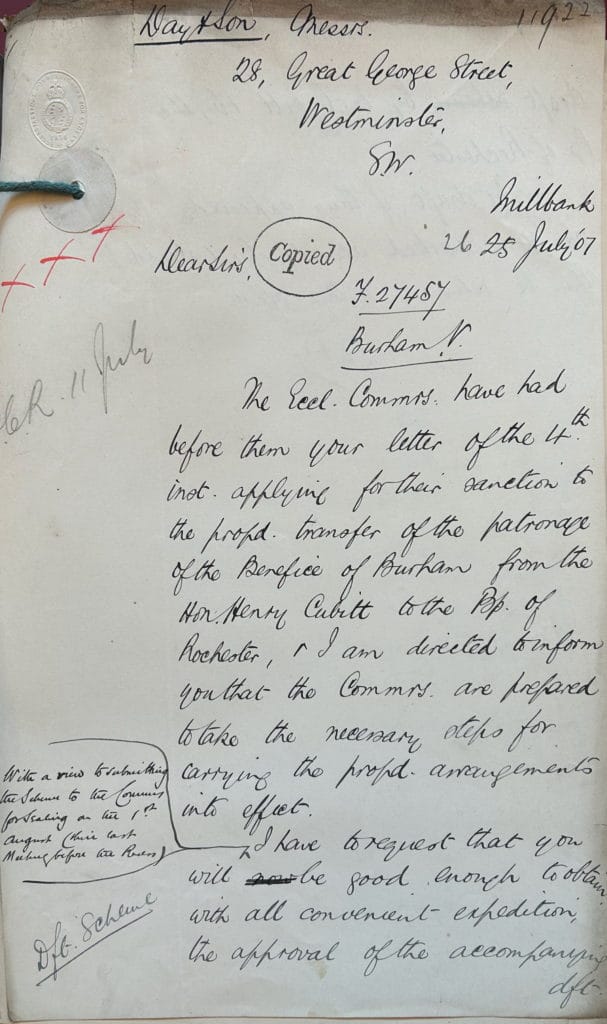

- 1871 – The Burham Brick, Lime and Cement Company Ltd

- 1940’s – The site in the before it was cleared

- After the works closed

The periods of Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers and Blue Circle ownership have, quite deliberately, not been examined. Partially, as there are almost no extant accessible records due to the disappearance from view of the Blue Circle archives.

General background

Cubitt owned, in the final years of his life, a substantial brickworks at Burham which then increasingly became a cement works and after Cubitt’s lifetime a substantial lime works. It was not unusual for large scale builders and contractors of the era to either have brick and/or lime works and later cement works.

In fact, it was only an operational brickworks under the Cubitt banner from 1851/2 to 1859 and a cement works from ~1853 – such a short period of time that it was almost certainly not worth the management time or massive investment.

Cubitt commented in a letter of 1853 [Cubitt -> C. Manby Bk III pg. 335] that the site was not ready for visitors and so we can assume it was still being constructed and expanded.

Sir Stephen Tallents, in his autobiographical work [Man and Boy, Faber & Faber, London, 1943 pg. 35], asserts that Cubit spent £80,000 “in equipping” the Burham Works which were just completed when he died. This phrasing suggests that the purchase of the lands was on top of this investment in the plant. It is unknown where Tallents derived this sum from as he gives no references. Tallents was related to Cubitt and discusses childhood summers at Cubitt’s mansion, Denbies, in great detail.

A far higher figure of investment is hinted at in the prospectus of the abortive attempt to form The Burham Brick, Pottery & Cement Company (1859), whose promoters attempted to raise £100,000 of capital, to buy the works from Thomas Cubitt’s executors, stating that the works were being acquired, for half of what had been invested in them. A larger value claim of £200,000 is made in the prospectus of The Burham Brick, Lime & Cement Company (1871), to buy the works from George Smeed and others, but allowance has to be made for a period of inflation.

So, what motivated Thomas Cubitt to invest huge sums of money in developing a new brick, lime, tile & cement operations at a time when his existing projects were running down in volume and he had not purchased significant additional lands to develop?

The answer a likely a mixture of Thomas Cubitt;

- needed to control the supply rate and quality of bricks so as to maximise build efficiency; and

- was so wealthy that he just could; and

- wanted to do it for a challenge [maybe to fulfil some of his earlier boasts in The Builder]; and

- realised that his present main brick fields in Caledonian Road were exhausted; and

- knew that high class neighbourhoods did not appreciate having a dirty smelly brick field next to them; and

- was an ardent campaigner for cleaning up London’s filth air; and

- wanted to make contoured bricks and tiles without the labour intensive cutting and rubbing post processing³; and

- consitent cement quality was quite the issue at that time.

It is also possible, that Cubitt was simply stepping in to fill the shoes of his existing lime supplier. It is unknown if the George Potter of Grosvenor Basin, Pimlico and Wouldham and Burhnam who was declared bankrupt on 23rd January 1852 [The Gazette 2nd January, 1852, 21278 pg. 19 – click to open entry] was a supplier to Thomas Cubitt but it is quite the coincidence in timing. Equally, it is possible that Potter’s insolvency could have been caused by Cubitt’s setting up his own internal supply chain. Potter’s works became known as Peter’s works after they were take on and developed by William Peters.

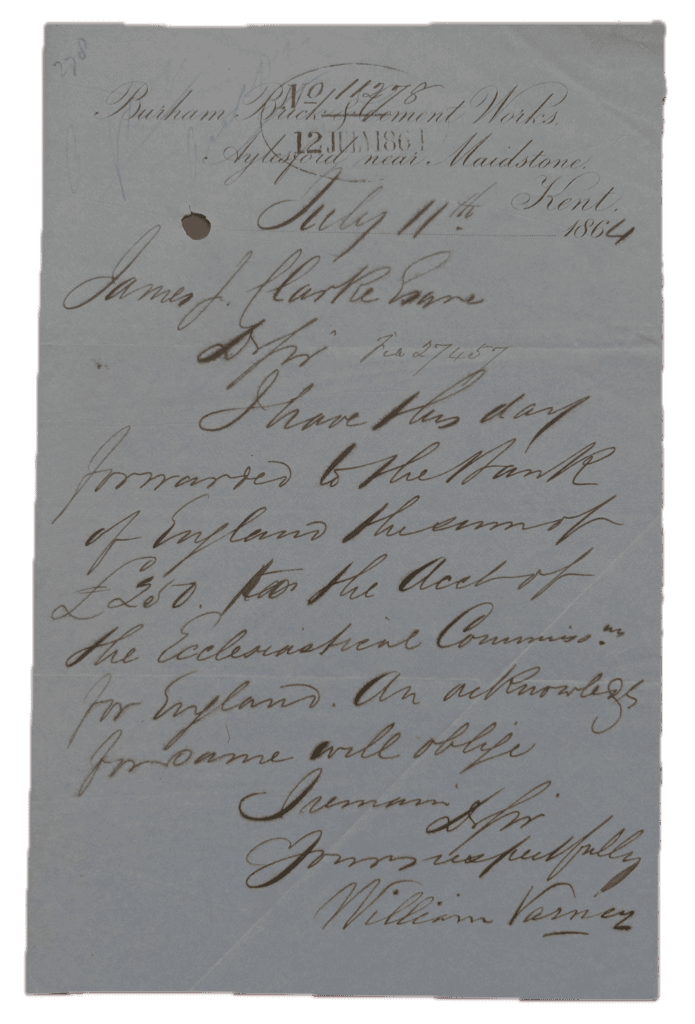

The the reason for the immense level of spending on the works could have been the immense trust he placed in William Varney, his brickworks manager! Certainly judging by the letter [below] which gives a considerable mandate to act in Thomas Cubitt’s name in banking matters.

3 Lyall St Belgrave Sq

15″ April 1851

Sir

The bearer Mr William Varney is the person authorise by

me to draw cheques on my behalf

to an extent to what you hold

funds of mine in your hands, until

further notice.

Yours etc

Thomas Cubitt

Mr Thomas Green[?]

Manager of the Maidstone Branch

of the London & County Joint Stock

Banking Company

The location was, almost certainly, influenced by the putative Mid Kent and Dover Railway, 1851. This would have offered the Burham works a connection to the main line. The proposal was published in The Gazette on 26th November, 1850, Issue 21157, Pg. 3174. However, this project was effectively killed off by fierce objections from other railway companies as well as various major landowners who turned against the scheme. The various schemes are, briefly, discussed further down the page.

Brick making in the 1850s and prior

In Georgian, and prior, construction bricks were made locally to the development due to the difficulties of transporting such heavy weights and distant with a horse and cart. This lead to pretty unpleasant environments around such developments as brick fields produced plenty of soot and smells as the bricks were fired by burning a variety of unpleasant materials to increase the firing temperature.

Cubitt had extensive brick making activities on Thames Bank, using Aninslee Machines described in The Builder, 27th May 1843, pg. 195 [opens the full article]. He also had a major brickfield for excavating clays, then taken to Thames Bank, at Caledonian Road which was by the 1850’s exhausted and the land was by then also then valuable and desirable for development.

Hobhouse [Cubitt: Master Builder NY, 1971, pg. 307] suggests in relation to the wording of an article in the Illustrated London News in 1844 issues January 1845 [this reference does not appear to be correct as it is not possible to track the article down in the British Newspaper Library].

The article apparently stated:-

‘At length, Mr. Cubitt, on examining the strata, found them to consist of gravel and clay of inconsiderable depth; the clay he removed and burnt into bricks, and by building on the substratum of gravel, he converted this spot to one of the most healthy, to the immense advantage of the ground landlord and the whole metropolis. This is one of the most perfect adaptations of the means to the end to be found in the records of the building art.’

Hobhouse’s, very salient comment is:-

This passage, written in 1844, perhaps exaggerates Cubitt’s acumen in making bricks in Belgravia, which was being done at the same time by Seth Smith and other builders, but is worth quoting as an example of the growth of the Cubitt legend even in his own lifetime.

In that context it is, perhaps worth take note of the acerbic comment made by James Spiller, the Estate Surveyor, during the Calthorpe Estate development: he states in an office copy dated 5th April, 1819 ‘he [Cubitt] has however unduly excavated a part for the clay of which he has made many indifferent Bricks’.

Presumably, Cubitt improved his brick making prowess in the intervening period?

Hobhouse states that Price Albert purchased brick/tile making machinery for the estate at Osborne House from Thomas Cubitt, possibly having seen the write up in the Illustrated London News in 1844?

Interestingly Cubitt is still asking The Ainslie Brick Machine to agree to some modification in a letter of 25th November, 1851 [below]. The way this is done make it clear that The Ainslie Brick Machine Co have control of this.

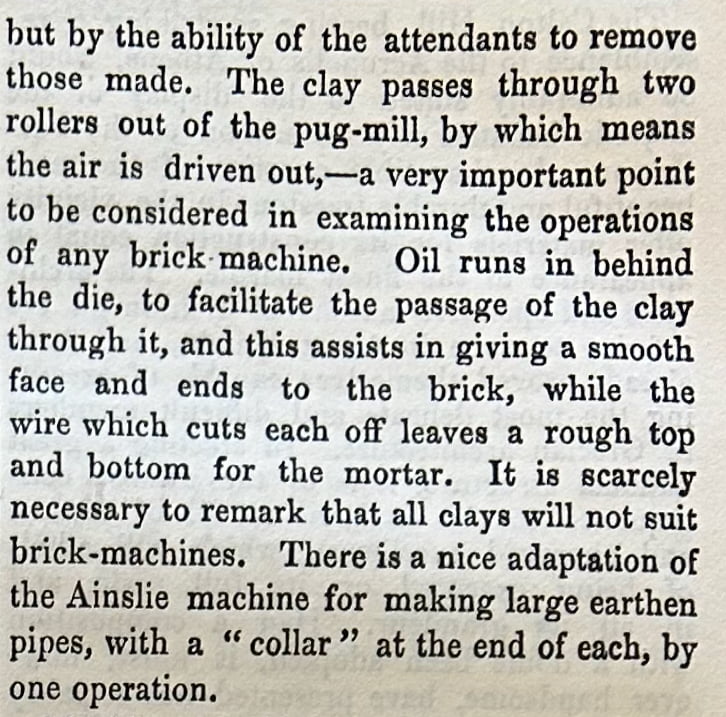

Kathleen Watt in her PhD thesis entitled “Nineteenth Century brick making Innovation in Britain: Building and technology Change [1990, pg. 135]” discusses the Ainslie machines at Burham

In discussing the Ainslie machines improved by Thomas Cubitt and used at his large works at Burham on the Medway, Hermione Hobhouse illustrated the new roller machine patented in 1846, but cited an 1852 description of Cubitt’s works in The Builder. This article clearly mentioned the clay moving through a die: “The clay passes through two rollers out of the pug mill, by which means the air is driven out…011 runs in behind the die, to facilitate the passage of the clay through it” (The Builder 1852, pg. 285; Hobhouse 1971, pg. 313). This suggests that Ainslie’s earlier patented machines rather than his roller extrusion machine were more commonly known and adopted.

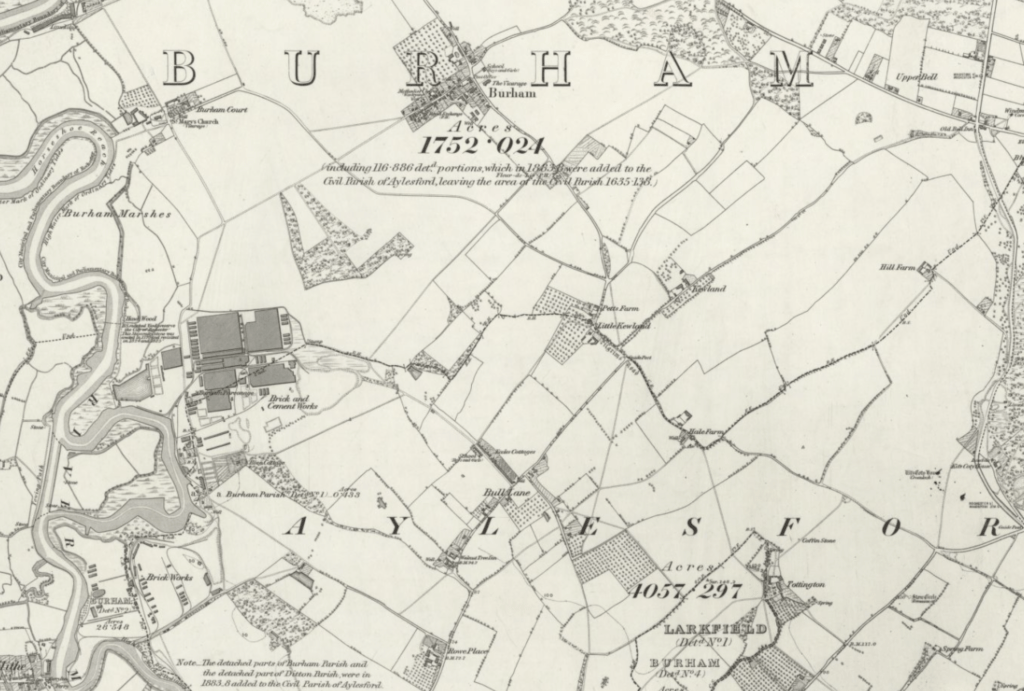

Why Burham?

This is a question that has puzzled many authorities, amongst them Dylan Moore [Cement Kilns website page on Burham]; John Fletcher with Chris Down [in their pamphlet Burham Cement Works, The Industrial, No 156, 2016] – as the site has never had any direct rail access for exporting either the bricks or the cement. Cubitt was quite used to barges delivering to his massive Thames Bank works and so the river access at Burham, via The Medway, would not have been seen as a direct barrier.

Another reason, could well have been, that all of the good sites had already been taken. Supported by the exceptional skills of his solicitor, James Hopgood, Cubitt was able to assemble the patchwork quilt of relatively cheap lands into a massive industrial site.

Prior to Cubitt setting up the plant, there were been persistent attempts to build what was sometimes styles as The Mid Kent [Landowners] Railway. It might well be that Cubitt saw this as an issue which would solve itself shortly.

Initially ~1845 this was to have been an atmospheric railway, with a mainline and two branch lines which appear to be single tracked one of which passes Burham. The overview map of the proposed layout is partially reproduced below.

By 1851 the scheme had metamorphosed into a conventional railway with a mainline and a grandiose junction to a branch line to Maidstone. The junction itself would have left a substantial area of close to unusable area of ground in the midst of the growing West Kent Gault Brick & Cement Company works. So it was perhaps not the ideal track layout for his purposed?

Cubitt clearly was not happy with this track layout as is abundantly clear from the his letter of 24th Dec, 1851 to East Kent and Maidstone Railway. Equally he clearly states, at hte foot of page 1, that ‘…I have no wish to have the railway…’ which is a very strange comment from an individual who was a heavy investor in railway stocks and was in the process of proudly putting as much railway and tramway track as he could fit into his works!

There was a further 1852 scheme with a different track layout shorn of the grandiose Burham Junction.

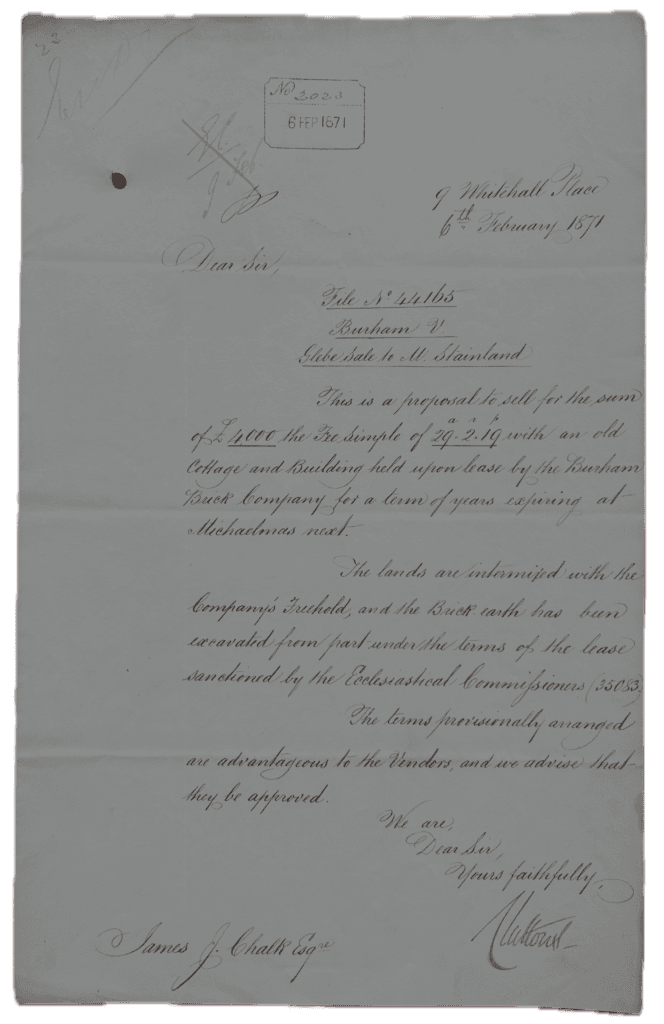

Acquisition of the various parcels of land and existing works

There was probably a small limeworks and brickworks on, or close to, the site that Cubitt ultimately chose.

Cubitt’s was limited in his choice of locations as many of the best ones had already been taken. The two things that Cubitt didn’t lack at this stage in his business career were ready cash and ambition to scale.

Cubitt had bought the Advowson to Burham, from a Colonel Milner, and this is set out in the First Codicil to Thomas Cubitt’s Will of 1855 and subsequently leased the Glebe lands which were close to the river Medway presumably for access to the river and wharfage. He also owned some local lands, prior to all of this, as he exchanged these in his 1851 bargain with the Earl of Aylesford: this is referenced both in the deed itself and in a letter from Thomas Cubitt to Henry Morris [surveyor] dated 22nd January, 1851 [Thomas Cubitt & Co wet copy letter book. London Archives LMA/4608/01/01/001 pg. 115] in discussion about proof of title.

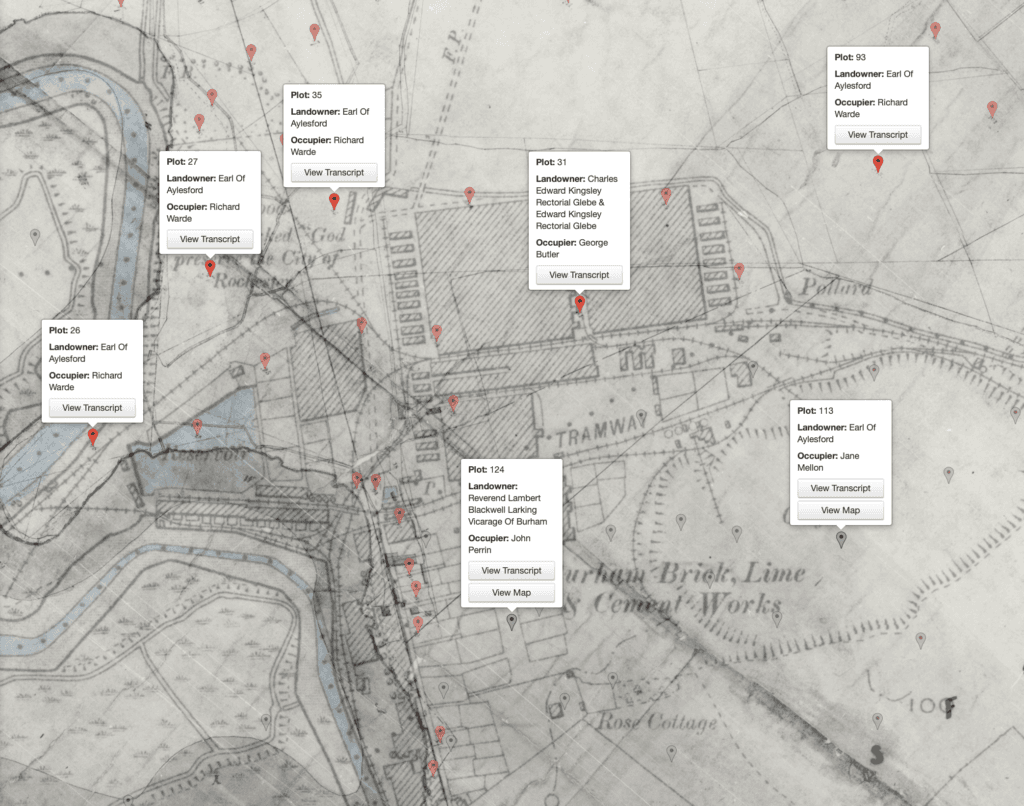

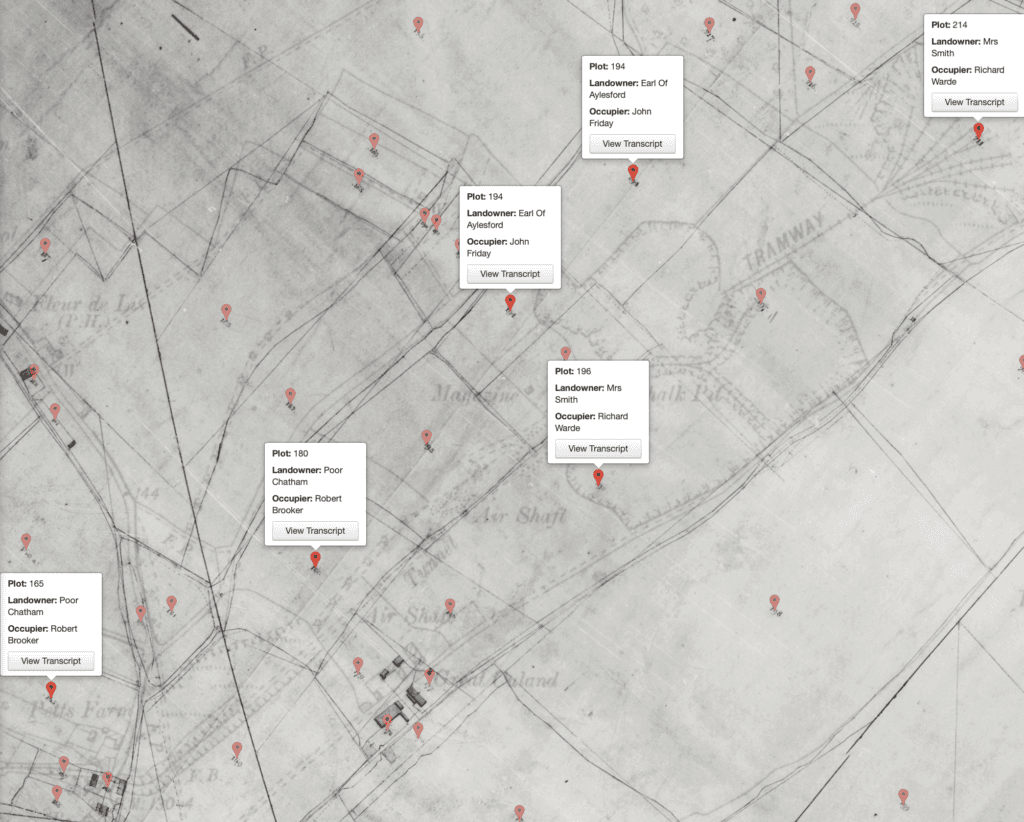

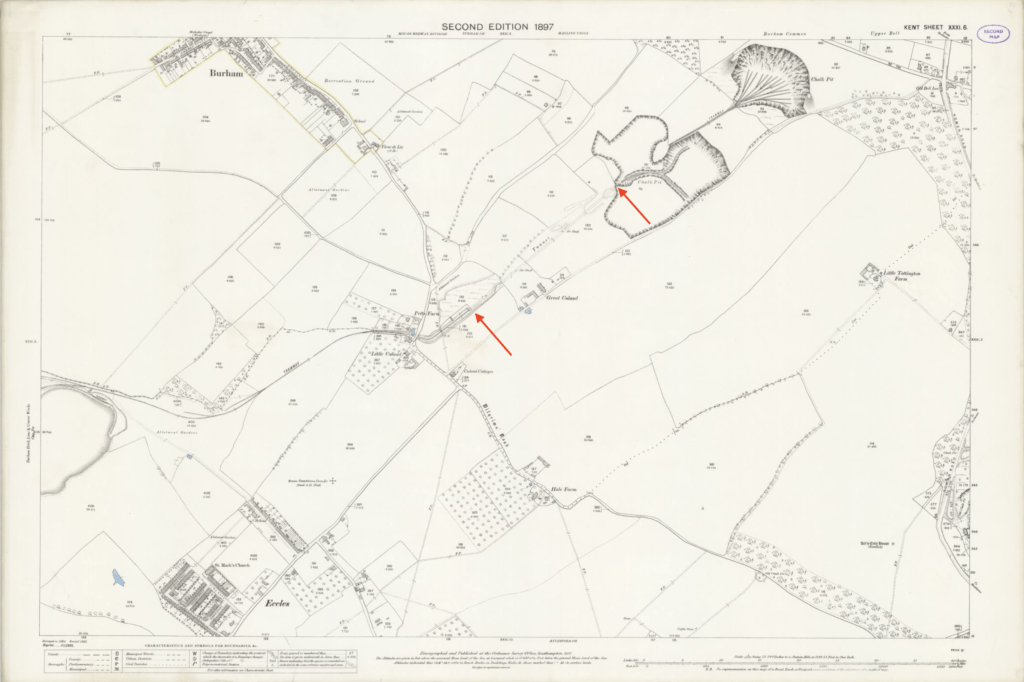

None the less, the site is made up of a highly complex mix of landowners; as these two overlay maps of the tithe maps with the early OS maps show. The working assumptions is that the works developed from a clay pit supplying a brickworks and then rapidly moved onto the self sufficient supply of chalk for the bricks, lime and cement operations. The scale of the chalk pits is absolutely huge and it testament to the volumes of material produced at the plant over its nearly 100 years of operational span.

Cubitt bought up various parcels of lands, all of these purchases are based on primary source documents that are sadly shorn of their deed plans;

- Earl of Aylesford – Lands in Aylesford being 2a.2r.26p [formerly with Ambrose Ward]; and 12a.2r.10p [known as Reed Hills] transacted ~29th September, 1851 – for the sum of £1055. Offset with a land swap of 9a.1r.23p of lands also in Aylesford. From a draft signed by Ja[mes] Hopgood p.p. Cubitt on 19th August, 1851 [Kent Archives U234/E4].

- Earl of Aylesford – Lands in Aylesford being being 9a.1r.23p, South West & North West of the high road leading from Aylesford to Burnham and Rochester. From a draft agreement to produce deeds dated, 26th February 1853. No consideration sum is stated. [Kent Archives U234/E4].

- Earl of Aylesford – two piece of land in the Parish of Aylesford being Rowe Place 12a.2r.10p and part of Burham Court Farm 2a.2r.27p by indenture dated 26th April, 1853. Stated in a statutory declaration made by Roland Bennett dated 19th March 1860. No consideration sum is stated. [Kent Archives U234/E4].

- Earl of Aylesford – copy indenture dated 27th April, 1853 – Burham Court Farm 2a.2r.20p; and 2a.2r.27p of arable lands; and 12a.2r.20p Reed Hill part of Roe Place Farm. Consideration sum £2,555 although this is crossed through with the word four annotated in pencil above it. However, the signature page states £2,555 which is unaltered. [Kent Archives U234/E4].

- Indenture of 25th June 1885, agreeing the terms of the mortgage of the Burham Brick, Lime & Cement Co Ltd, states that the sums paid were £395 2s 7d; and £3500; and £7,100; and £22,000 giving a total value to the lands purchased of £33,045 2s 7d although it doesn’t quite state that these were the Cubitt purchase sums but it is presumed that they are. The £22,000 would be an unbelievable sum in the 1850’s so it is suggestive that this was a later transaction, likely the 1885 transaction, when land prices has substantially inflated. [Kent Archives U234/T4].

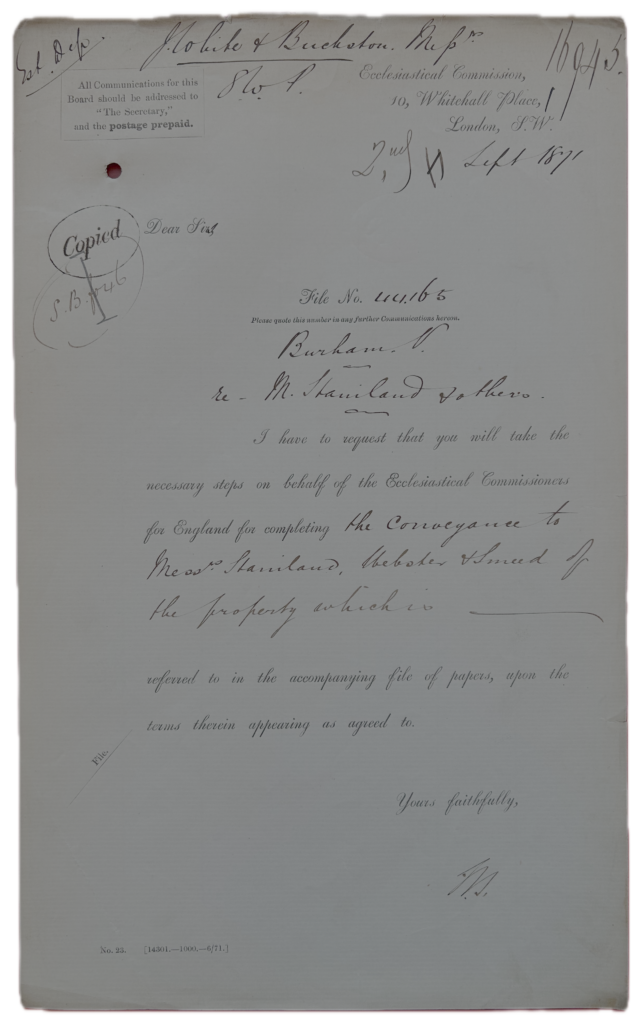

- The Glebe Lands of Burham – 1851 agreement with the Ecclesiastic Commissioners – 1st December, 1851 [Diocese of Rochester].

- Petts Farm – unkown agreement relating to the bridge/tunnel under Rochester Road and the cuttings either side of it and likely later the half mile tunnel and vent shafts

- Culand Farm [Kewland Farm on 1st Ed OS maps] – unknown agreement relating to the lands on which the chalk pits were excavated.

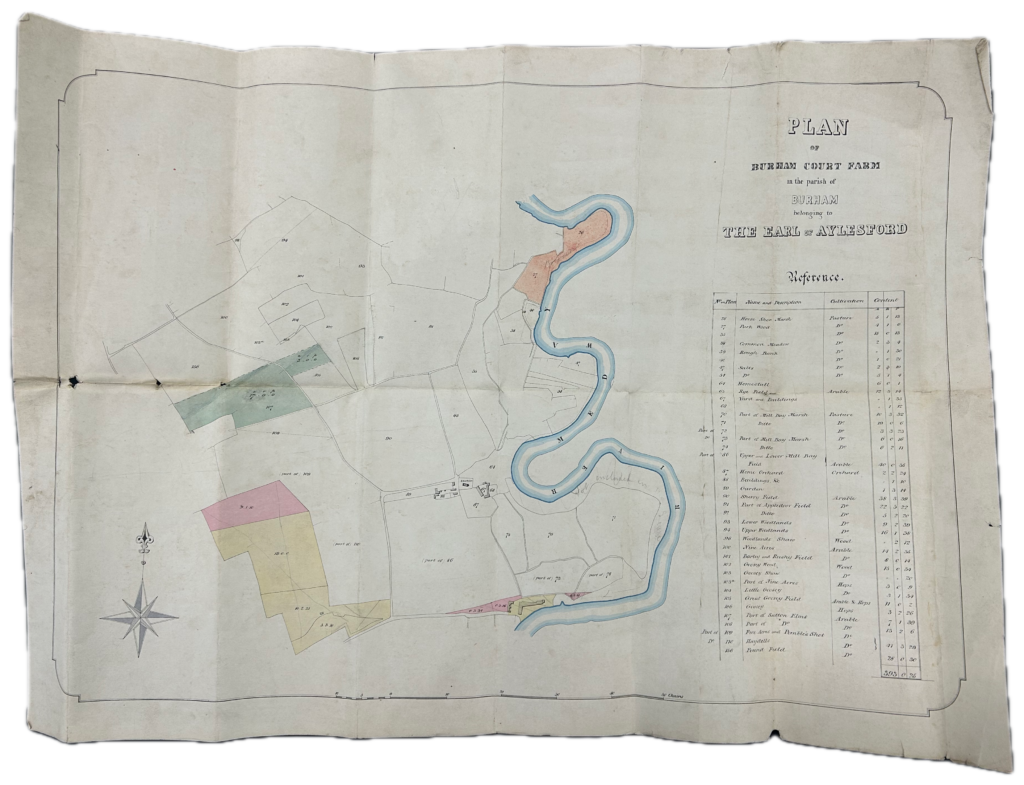

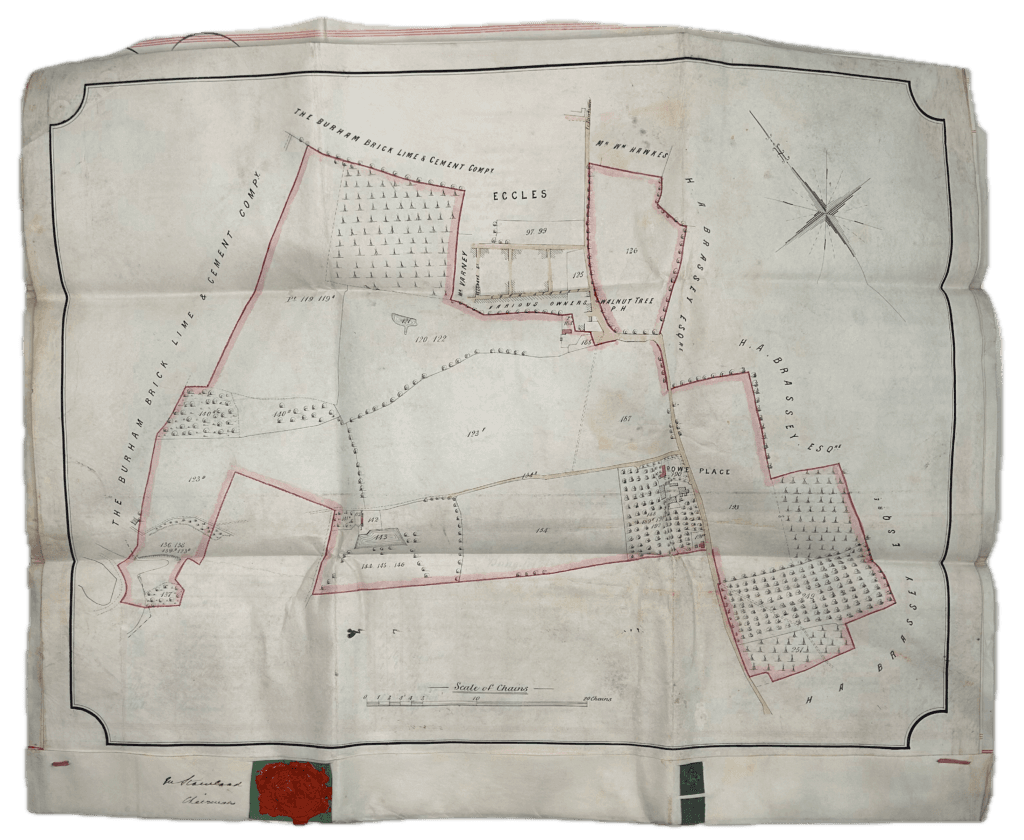

Burham Court Farm – Earl of Aylesford

A near contemporary plan [below] of Burham Court Farm was found in a different set of records: an agreement for the farm, dated 11th October, 1856. However, it does appear to have been copied from the Aylesford Estates Ledger: the plot numbering; and areas; and tinting of the areas is also coherent with the Cubitt – Aylesford deeds. Importantly it is reflective of the period immediately after the initial land transactions and the establishment of the works by Cubitt in 1851-3.

The map’s orientation doesn’t make sense of the compass marked on it when compared to other mapping sources such as Ordnance Survey. In fact the map appears to have flipped North for South on comparison to an Ordnance Survey map of the period.

Plots 26 & 27 coloured brown on the plan are, for sure, a part of the Cubitt works. Plots 105 & 107 tinted green could possibly be the areas of land being conveyed to Lord Aylesford by Cubitt in the 19th August, 1851 deed [Kent Archives U234/E4] which contains the language, also in consideration of the said Thomas Cubitt conveying to the said Earl of Aylesford or as he shall direct…..which piece of land is delineated in the plan hereinto appended(?) being coloured green, although it has to be noted that the acreage is not correct. What this does tell, with a degree of certainty, is that Cubitt had started to acquire lands for this project prior to 1851 and from their location they would likely have been for chalk quarrying.

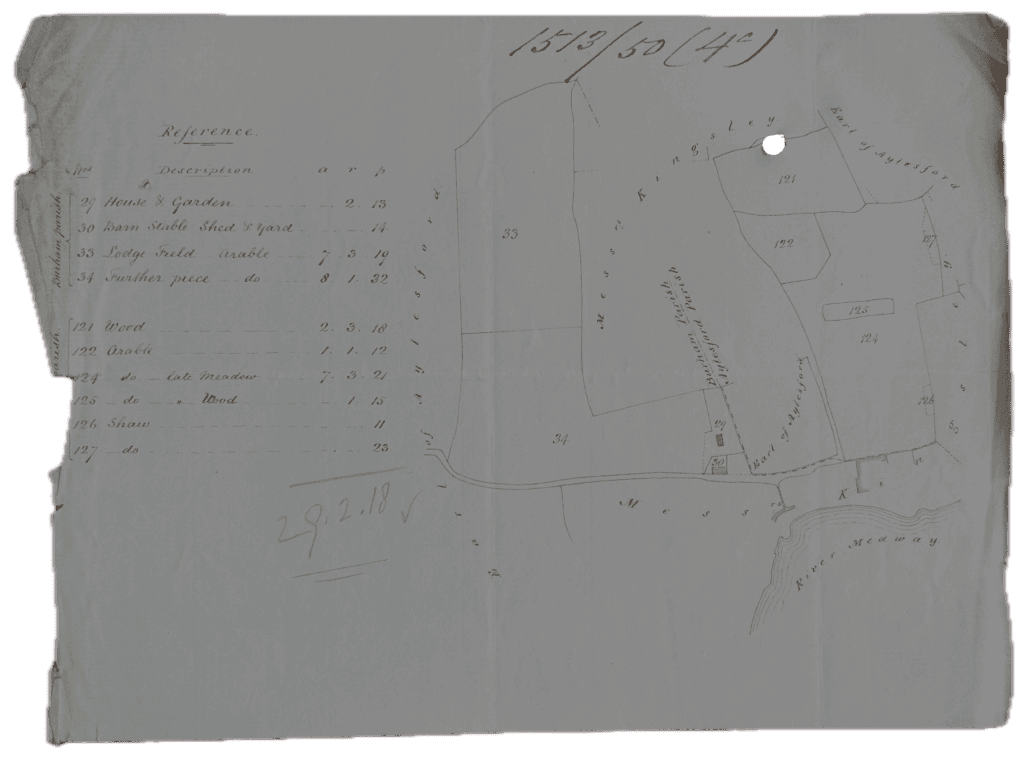

At least part of the 1885 transaction is available as a clear deed plan [below]. It is something of a mystery why this land was transacted as most of it never appears to have been used by The Burham Brick, Lime & Cement Co Ltd. However, it could be that this was simply an astute move to thwart the West Kent Gault Brick & Cement Company’s ambitions and indeed it allowed The Burham Brick, Lime & Cement Co Ltd to abort the Earl of Aylesford’s attempts to grant a right of way across these lands.

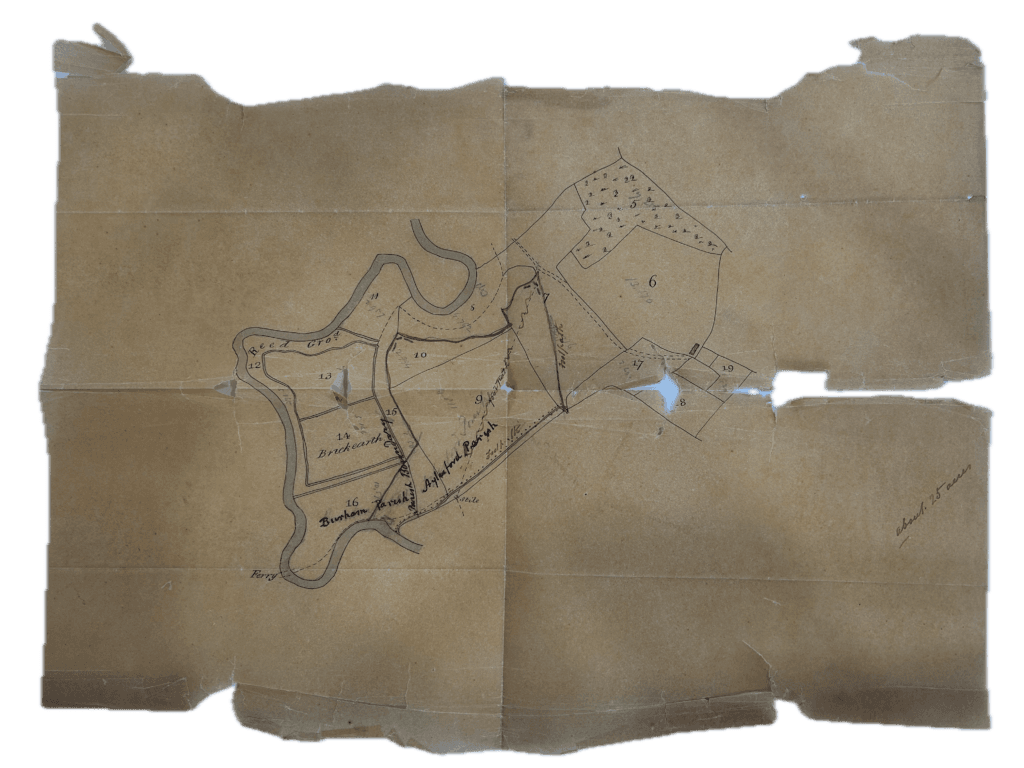

This fascinating plan [below] believed to be of the West Kent Works site – the marking of the Burham/Aylesford parish boundaries initially drew attention to it, is included giving an insight into the negotiation processes that lead to the these works.

Frustratingly, superbly preserved auction plans exist for both the Burham Lime Works [Kent Archives U1644 E120-122 with auction catalogue description for both sites] and for the West Kent Gault Brick and Cement Company [Kent Archives SP/COLL/65/1 in near perfect condition] from the 1884 auction catalogue plans.

The negotiations, between Thomas Cubitt and Henry Morris [Surveyor] – Earl Aylesford’s representative, were far from plain sailing. Generating a total of eleven letter from Thomas Cubitt’s hand.

[Bk refers to the volume in the series the series of Thomas Cubitt & Co letter books I – VI – Hobhouse describes them as books A-E – the books are held in the London Archive LMA/4608/01/01/001-006 – there is a searchable PDF of the indices, generated for this work, in their online catalogue].

Thomas Cubitt Letter Book I – 20th Sept 1850 – 12th Nov 1851 [London Archives LMA 4608/01/01/001]

24th September, 1850 – Pg. 4 ‘Would it be convenient for you if I come to Maidstone on Friday 11 + 12 O’Clock or if that day is inconvenient to you on Saturday or Monday next at the same time.’

10th October, 1850 – Pg. 36 The first page of the letter is largely illegible as it has shifted in the wet press ‘….I shall be glad to know whether you think I [???] make my engagements with Lord Aylesford so that I may get part of Reed Hill, as well as of the 2 acres piece. Forgive me for troubling you with these enquiries. I wish to know to decide now as to the arrangements of working the Ground. Who shall I send the £118.17.0 to? To you or to the tenant? I suppose it might not be paid to the tenant till I get possession.’ This letter is, potentially, quite important as it does ask about a hill as this would suggest an early requirement for chalk supply. This would suggest that there was an early plan for cement making.

31st October, 1850 – Pg. 57 ‘Will it be convenient to ??? see you if I come into Maidstone on Friday afternoon. I hope that I am not presuming upon you too much when you are busy.’

21st December, 1850 – Pg. 99 ‘I have received your letter of the 13th regarding the land. There appears to be such a great difference of opinion between us as to the value of the land that I suppose that no arrangement can be made. I should however be glad to see you I would much obliged if you can name one or two dates on which you think it would be convenient to you to be at your Office after the 26th.’

27th December, 1850 – Pg. 102 ‘I have to thank you for your letter of the 23rd + I beg to say that I will call upon you at Maidstone on Tuesday ???? the 31st at about 1[?] O’Clock.

2nd January, 1851 – Pg. 107 – This letter is largely illegible and appears to have been written on a train. It appears to arrange yet another meeting in Maidstone on Thursday.

22nd January, 1851 – Pg. 115 – ‘I beg to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of 18th inst: on the subject of the Exchange with Lord Aylesford. I would rather that the expense of the Conveyancer should have been borne equally: but as they cannot come to much I will not make it a point.

With respect to my title, it has as you know just been investigated on the occasion of my purchase + it is I believe quite satisfactory; it must be understood that Lord Aylesford will be satisfied with the same title as has just been made out to me. I will make + maintain the fence you refer to. I will give instruction to my Solicitor to prepare and abstract of my title + shall be glad if you will give similar instruction to his Lordships Solicitor.’

14th February, 1851 – Pg. 150 ‘I understand that the piece of land set out upon Lord Aylesford’s Estate is larger than was larger than intended by our agreement; I do not know who set it out, nor how this occurred, but if it is agreeable to you + his Lordship to let the demise as set out I shall be willing to pay you the difference.’

8th March, 1851 – Pg. 187 ‘I have received your letter of the 6th inst. + am willing to pay the difference you mention. My Solicitor is Mr James Hopgood 14 King William St. Charring Cross + he will be ready to attend to this business as soon as his Lordship’s Solicitors communicate with him.’

Thomas Cubitt Letter Book II – 12th Nov 1851 – 25th Oct 1852 [London Archives LMA 4608/01/01/002]

15th January, 1852 – Pg. 89 Legibility of the text is poor but it appears to be concerning the final accounts for the land transaction ‘I enclose a Cheque for your account which I have just received + I beg to thank you for your attention to these little matters. Please to ?????? will you have the goodness to let me know as soon as you conveniently can the account showing what I ??? to receive from ?? ??????’.

13th July, 1852 – Pg. 317 Cubitt states that he has bought a friend’s estate as it did not sell at auction and asks for Henry Morris’ help with the matter. A substantial part of the text is illegible.

The priority that Cubitt accorded setting up the Burham works was clearly very high, as Cubitt was travelling to Maidstone to meet H[enry] Morris Esq. Surveyor. What is very clear is that Cubitt is handling all of the negotiations personally. A time consuming business and possibly quite unpleasant for a man with arthritis in the midst of winter.

The later letter books, do not appear to have letters to Henry Morris concerning the 1853 Earl Aylesford land transactions: so it is possible that either this was done in person or that another party was acting for Earl Aylesford, by this juncture.

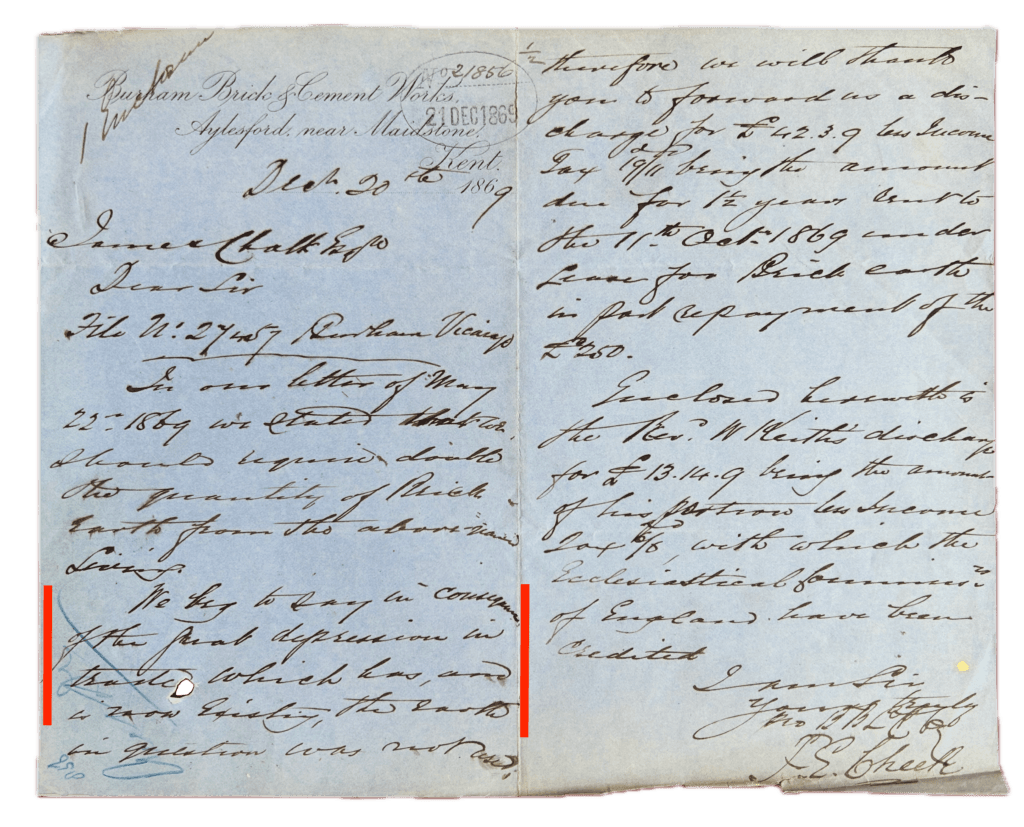

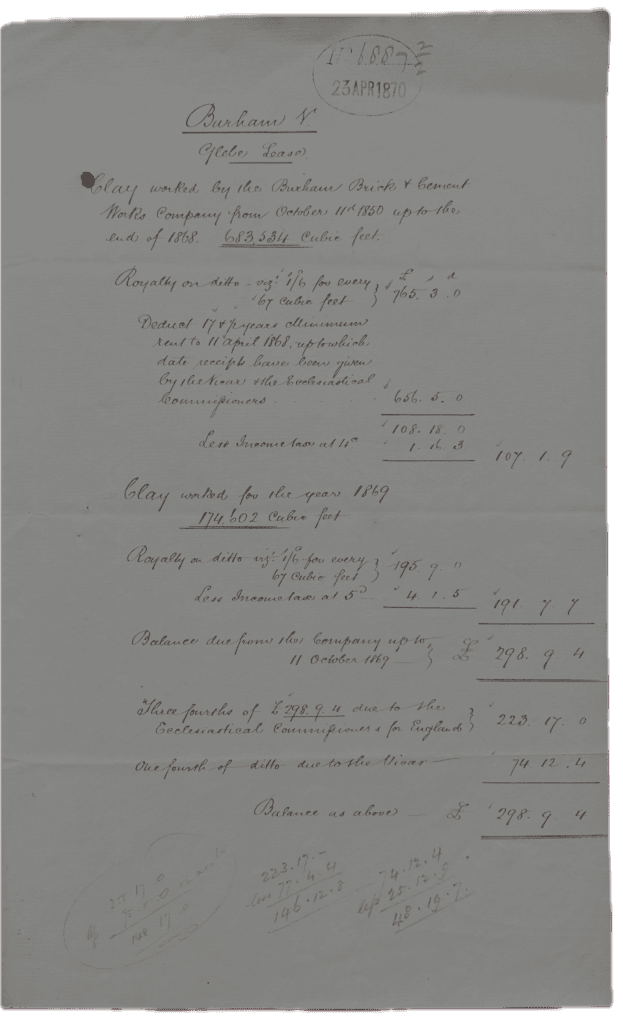

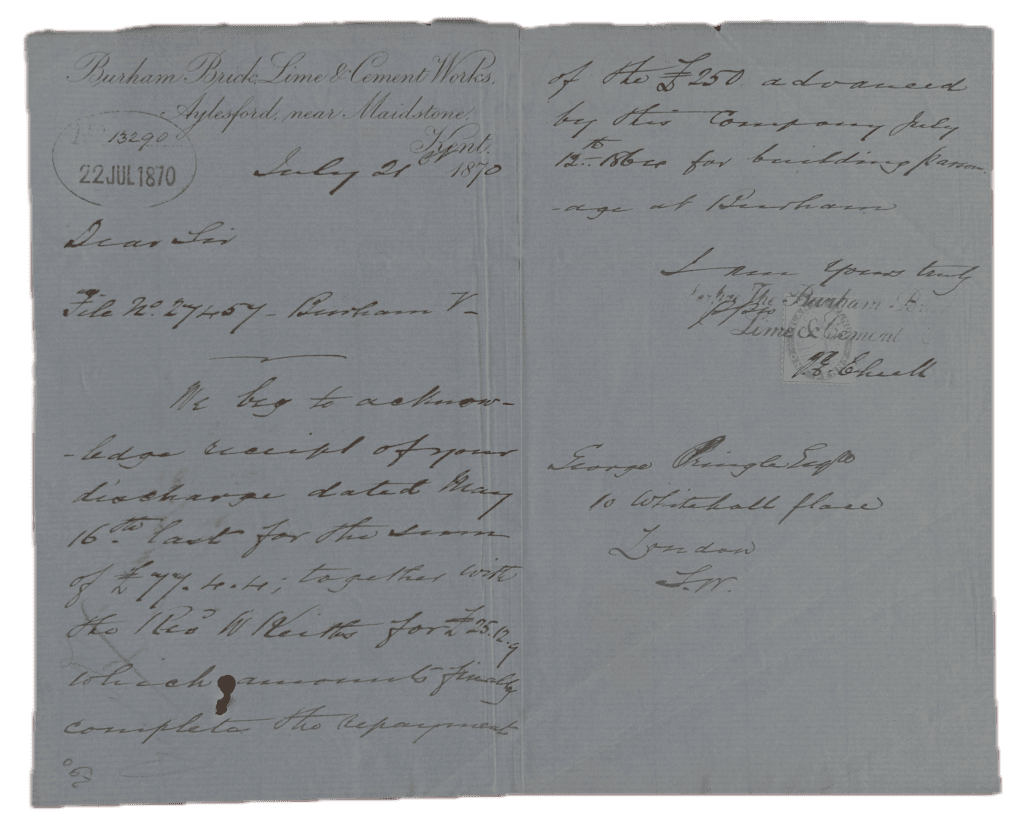

The Glebe Lands of Burham Parish – The Ecclesiastical Commissioners

Cubitt purchased the advowson, presumably, so he could put his own man in to control the Glebe Lands from a Colonel Milner.

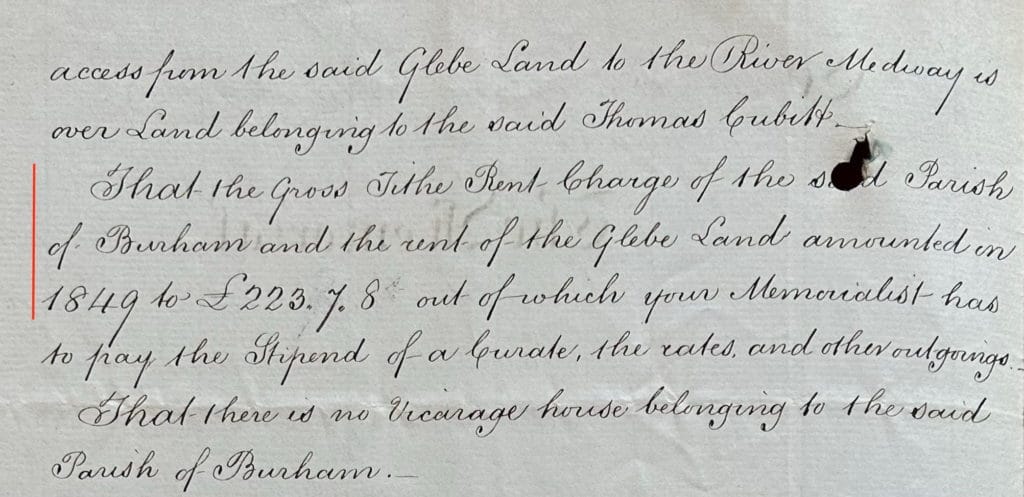

Undated plan of The Burham Glebe Lands [below], possibly that referred to in the undated memorial from the Incumbent, Lambert Blackwell Larking, to The Ecclesiastical Commissioners showing the ownership and uses of the lands prior to Cubitt’s bargains.

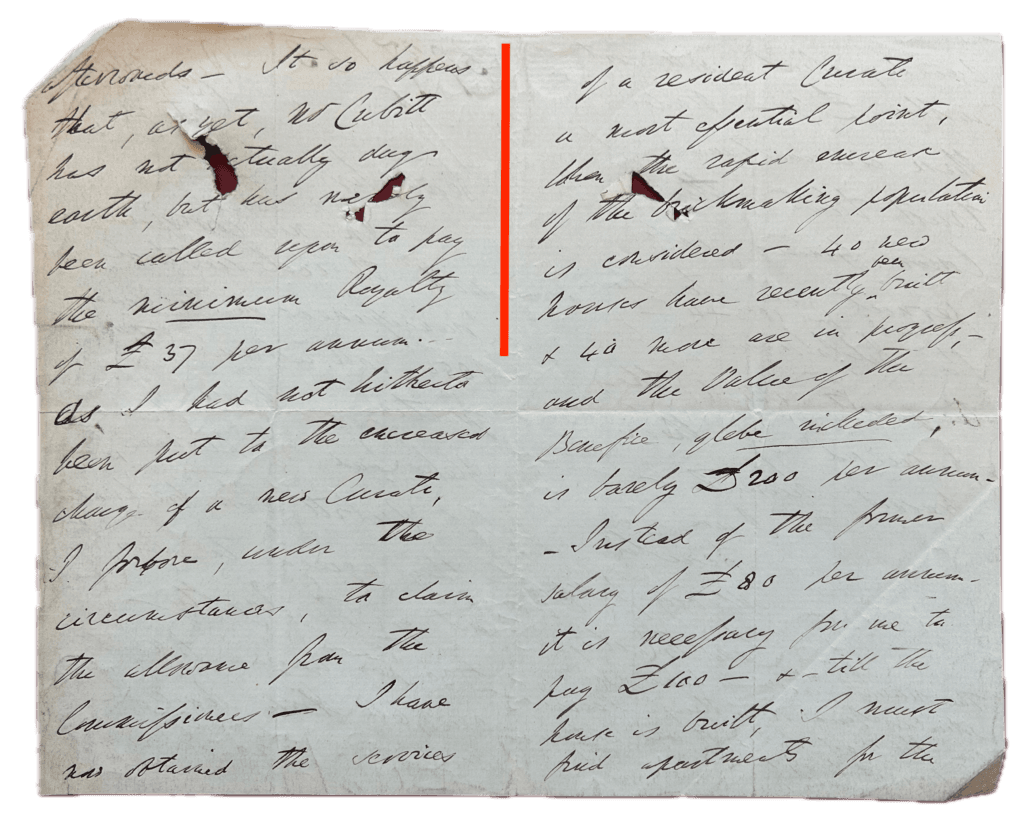

In an undated memorial [Lambeth Palace Archives – ECE/7/1/70542 – below], the Incumbent writes to The Church Commissioners setting out the proposed heads of terms: as advised by John Clutton. ‘A surface rent of £40 is proposed with a royalty charge of 1s 6d for every 67 cubic yards of brick earth manufactured into bricks tiles or other articles…..‘ the Incumbent goes on to assert that ‘ ….The Gross Tithe Rent Charge and the rent of the Glebe Lands [unfortunately the two incomes are not distinguished] amounted in 1849 to £223 7s 8d’.

So, a bad bargain for the Incumbent was arrived at. Which was published in The Gazette on 24th October, 1851 21256, pg. 2775 [click link for full text as PDF of the original].

Files held at Lambeth Palace Archives [ECE/7/1/27457/1 – for instance a letter dated 12th November 1872 from William Keith, Vicar of Burham to The Ecclesiastical Commission reciting the overall deal] show that the yield from the Burham Glebe Lands was split with the majority of it, three quarters, going to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and one quarter to the incumbent.

One thing that does shine though is that Thomas Cubitt quite deliberately contracted, via the lease, for a royalty based payment system based on clay/brick earth extracted from the grounds and no payment at all for the holding of the lease. A cursory examination of the tithe maps above shows that the majority of the enormous works were built on The Burham Glebe Lands and the clay pits were seemingly on land purchased from the Earl of Aylesford this was quite the ruse for some rent free lands for his massive factory! Indeed the vicar of Burham writes to The Ecclesiastical Commission complaining of this in a letter of 24th October, 1853 [below].

As if that wasn’t cynical enough, Thomas Cubitt owned the Advowson of Burham [the right to appoint the incumbent]; so Thomas Cubitt’s was Lambert Blackwell Larking’s Patron!

Perhaps our Mr Cubitt was being less than entirely straight forward in the bargain he entered into for The Burham Glebe Lands?

Even so, there was constant wrangling concerning the royalty amounts due to be paid for the clay/brick earth.

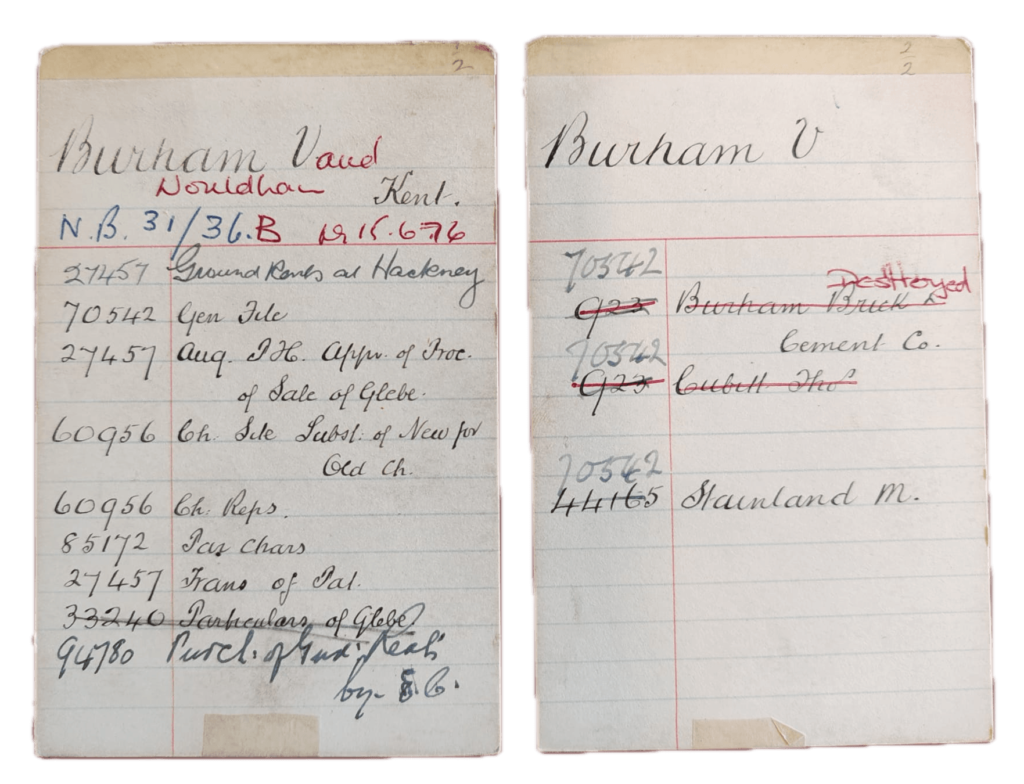

Tantalisingly there is an index card [below] from the old Church House Archives. This shows that there were originally separate files for the Burham Brick & Cement Company and most interestingly for Tho[ma]s Cubitt himself. However, these had a single convergent file reference number. Sadly this file is marked as destroyed, presumably in 1976, as the hand and ink colour look similar. However, it would appear that very substantial parts of those files were transferred into #70542 which we have integrated in the above.

Letters from Thomas Cubitt & Co to Rev Lambert Larking

[Bk refers to the volume in the series the series of Thomas Cubit t& Co letter books I – VI – Hobhouse describes them as books A-E – the books are held in the London Archive LMA/4608/01/01/001-006 – there is a searchable PDF of the indices, generated for this work, in their online catalogue].

The numbers beneath are the numbered pages in that volume. The upshot of this copious cannon of letters, is that once Cubitt had secured the Burham Glebe Lands he became quite evasive towards meeting Rev Lambert Larkin. Cubitt was, manifestly, a very busy man and sending Mr Ward to deal with the matter of the grounds for the proposed new parsonage and school doesn’t seem unreasonable. However, it is abundantly clear that once Cubitt had got what he wanted from, Rev Lambert Larkin: he wasn’t of immediate use but that he had to be kept sweet.

Bk I – No references

Bk II – Pgs. 142, 169, 215, 216, 222, 262, 313, 341

Bk III – Pgs. 81, 130, 131, 193, 228, 305, 389, 391

Bk IV – Pgs. 14, 42, 66, 71, 72, 97, 113, 183, 208, 201, 227, 293, 387, 417, 418

Bk V – Pgs. 13, 30

Petts Farm – The Sir Edmund Gregory Charity

Petts Farm [sometimes Pett’s Farm] whilst not seemingly a part of the Cubitt’s initial land transactions is central to understanding the development of the chalk quarrying side of the Burham works.

The railway line [tramway on contemporary maps] for moving quarried chalk to the cement and lime works; with its cutting and tunnel running across the Petts Farm site. So the documented history of Petts Farm can give a clear insight into dating of the tunnel and therefore the vertical integration of the chalk quarrying operations. [is is possible that this is erroneous as the lands used were all of others – the misconception was due to a misalignment of the tithe maps and the OS 2nd edition maps].

The Sir Edmund Gregory charity founded on 24 April 1710, were the freeholders of Petts Farm until they sold it to the Burham Cement Works on 9th July, 1894. In fact Pett’s Farm was the sole asset of that particular charity. The proceeds of the letting of the farm were hypothecated to providing bread to the poor of Chatham so it was a highly significant asset that would not have been dispersed or disposed of casually.

An initial view might be that The Burham Brick & Cement Works would have needed a sale or lease of lands and/or an easement for the tunnel running under Petts Farm. [it appears that the Petts Farm lands were quite deliberately avoided].

The surviving records are partial but they do provide very clear indications. However, the Lord of the Manor, Earl Aylesford, would have owned mineral and subterranean rights so the only overarching agreements would have been with regards to the cuttings and the ventilation shafts which were on Petts Farm. The Culand Pits themselves were on Culand [Kewland] Farm lands owned by, the hard to trace, Mrs Smith. It is clear from The Chatham Board of Guardian’s minute books [discussed in detail below] that the chalk railway was fully operational prior to 1882 when a spark set fire to the Petts Farm Oast Houses.

Cubitt’s Setting up of the Burham Works

It is assumed that Cubitt started to set up the works in early 1851 on completion of the lease with The Ecclesiastical Commissioners for The Glebe Lands.

How the works evolved so rapidly into their massive shape and scale is shrouded in mystery. Was there a master plan? Was there an intention to produce cement from the off? Was the geology of the local chalk deposits fully understood? There are currently no clear answers.

The brick works were rapidly set up and seemingly producing some output by ~1852 as there are extant letters [Letter Book III pg. 66] offering to supply bricks to others in Cubitt’s hand.

Oddly there are, seemingly, no letters from Thomas Cubitt to William Varney in the earlier letter books that survive. This is particularly strange as there are letters to The Ainslie Brick Machine Company and Kent Railway Company in those same letter books.

The later letter books, post Thomas Cubitt’s death, devote a large percentage of their output to the Burham Works and its sale in one shape or form.

Cubitt’s Burham works are described in overly glowing terms in The Builder 19th June 1852 pg. 385 [opens the full article] as operational. The article also name checks his Thames Bank works.

In 1852, Cubitt was in contact with a certain Mr Batchelor, regarding building kilns. It is possible that it is merely a coincidence but Batchelor cement kilns were previously not thought to have existed before the late 1860’s. It is intriguing to speculate that Burham could have been the test bed of the Batchelor kiln. There are another two aspect that lend some weight to this.

Firstly, Cubitt had extensively set up drying for bricks and tiles using waste heat. The Batchelor kiln essentially uses waste heat from the kiln to pre dry the cement slurry.

Secondly, Burham cement was very highly regarded to the extent that the plant was supplying the Metropolitan Board of Works in the 1860’s who were the first to have an exact testing scheme in place. In part this was likely down to the very high quality chalks that were used: of which more later.

Maybe it is all a coincidence but the fact remains that the letter is extant. The letter does mention Dorking but not too much should be read into that as there was little manpower around Burham at the time so many of the workers listed in the 1861 census are listed as coming from one area of Surrey or another. Further there was little accommodation in the environs of the Burham Works and a great deal of housing was indeed built, quite rapidly for the workers. So read in that context the letter can be interpreted in that manner.

[Dylan Moore is firmly of the view that this letter concerns the building of brick kilns and is not related to cement kilns at all].

However, the later is vague and it has no clear addressee, which is highly unusual for the Cubitt & Co letter books and sadly Mr Batchelor is not dignified with any initials nor an address to narrow the field via a census search.

[Insert Cubitt letter re works not being fully set up and expensive machinery being installed 1853].

Insert Cubitt 1853 Letter Book III Pg 60 in here with Cubitt complaining of people being taken away from the works.

Tile making

Very little is known about the tile making side of the business other than the adverts for a wide variety of tiles after Thomas Cubitt’s death.

There is correspondence in the letter books with Ridgeway, who was a part of a well established pottery family.

[insert references to the two Ridgeway letters].

The Development of the Cement Works and it’s Railway System

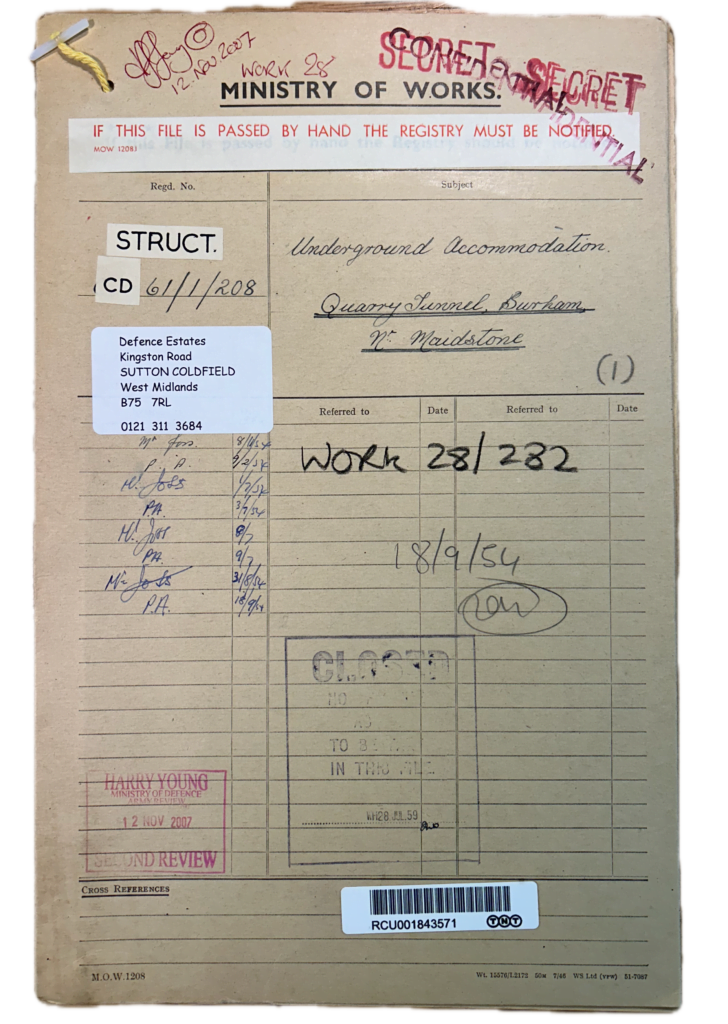

The half mile tunnel is located on private lands. The lower end of the tunnel emerges into a flooded cutting. The tunnel is blocked part way down its length by chalk fill that has been deliberately inserted via a ventilation shaft. The tunnel is a protected bat habitat and it is a criminal offence to disturb bat habitats.

Whilst the brick works was relatively quickly established by Thomas Cubitt and its layout is quite well established from the 1860 Smeed & Prall deed which is very similar to the 1st Edition large scale OS maps. Less certain is the development of the of the cement side of the works.

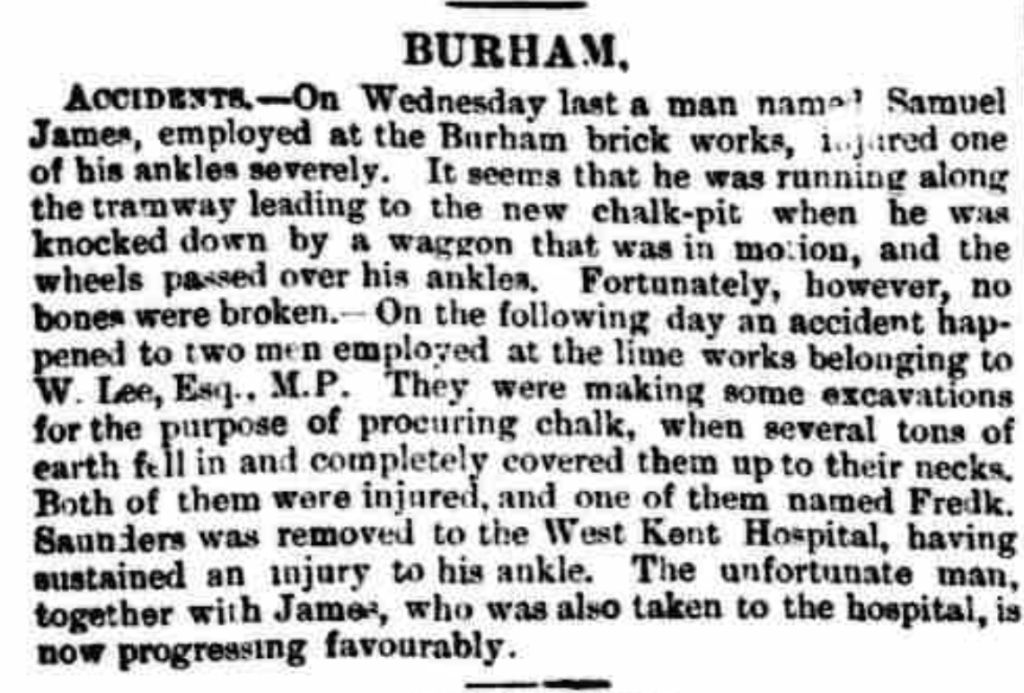

It had previously been postulated that the chalk quarrying, a basic necessity for cement production, did not start until the 1890’s based on OS mapping but this can be proved categorically incorrect based on extant minutes of the land owning charity [before 1882]; and adverts for the sale of the lime produced from the chalk [1869]; and record of an accident in the new chalk pits [1869]. It is perfectly possible that the ‘new chalk pit’ referred to was one of the further chalk pits. It can said with certainty that in order to be able to access any of those pits the tunnel must have been in operation, further it must have taken at least a year probably two to build it and then a period of time to plan it and acquire the lands.

It is clear that Cubit was hunting for lands to extract chalk on [Letter Bk IV Pg 1st Jan 1854 – below]. The letter is barely legible so the text is transcribed.

I beg to acknowledged the receipt

of your letter of the 30″ Decr.

With respect to the Lime I am

rather desirous of getting some Freehold

Land for the purpose & I have heard

of some which will probably ????, but,

I will ask my foreman do call & speak with

you upon the subject when is in

your neighbourhood.

Cubitt also clearly stated that he wanted freehold lands [Letter Bk IV Pg 153 16th Jan 1854 – below] from which it is reasonable to deduce that he wished to expand production of chalk based products. Chalk is required for brick, lime and cement production although the grades of chalk required do vary. So the precise locations chosen will give a substantial clue as the intended used for the production from the chalk pit.

Further, Cubitt turned down lands belonging to the Snodland Charity, possibly for chalk extraction [Letter Bk IV Pg 146 5th January 1854 – below] so it is clear that Cubitt was openly casting around the area for additional chalk bearing lands and that these were at least some of the responses that he was obtaining.

There is considerable correspondence between Thomas Cubitt and Gibson & Watts of Dartford in 1854 concerning a parcel of lands in New Hythe owned by a Mr Browning. This is the other side of the Medway from the works. Ultimately no agreement could be reached as Cubitt was not prepared to pay the values put forward. It is also possible that he wasn’t particularly interested in these lands as a source for materials as he already had Larkfields for sand extraction?

Dating the bride/ tunnel under Rochester Road /Pilgrims Way has proved to be a resource sink.

Cement making may be dated as started before March 1853 – 24th March, 1853, entry in the Burham Parish Minute book reads ‘That the new Cement Works at the Varnes be rated in the poor rate book the cottage adjoin gin at 7£ Mr Vareny’s House at 25£10s…..’ [Kent Archives, Aylesford Parish Minute Book, P12/8/1].

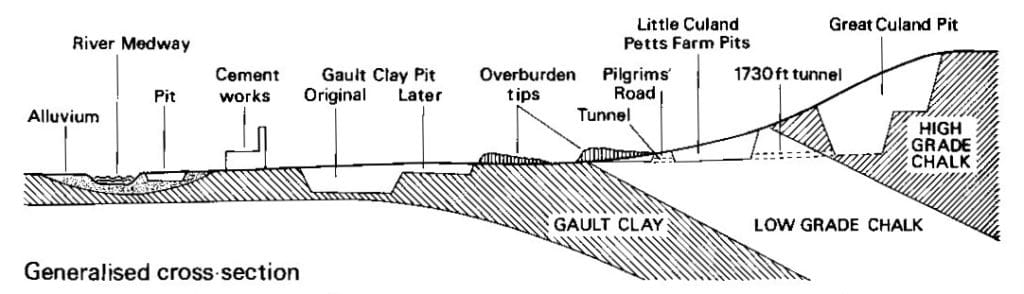

Key

A – Blue – 1853 [or earlier] bridge tunnel under the Rochester Road

B – Red – 1/2 mile tunnel portals

C – Yellow – 2nd chalk pit in use by ~1860’s – no direct evidence for this – but William Webster was producing very substantial tonnages of cement for The Southern Outfall Sewer at Burham by 1860, to a quality that satisfied Jospeh Bazalgette, which is suggestive of substantial supplies of high quality chalk.

D – Green – 3rd chalk pit ~1868?

E – Blue – The likely extent of the ~1853 quarry which became the cutting to the tunnel

F – Blue – Passing loop – which is pretty much equidistant between the works and the head of the tunnel suggesting cable winding. However the sharp bend by Petts Farm [A] would make this practically difficult.

It may well also be significant that the main engine for the works was a retired cable hauling engine “our old Blackwall Railway friend“. And that this was, at least initially, the mode of traction in the works judging by the phase that the “With the single exception of the coal which is conveyed from the wharf to the kilns and engine-house there is no up-hill traffic, and even this is considerably assisted by the down pull of the loaded waggons, which also, as they go down to the wharf, help up the empty wagons back to the kiln” from The Illustrated News of the World, 8 October 1859 text fully reproduced further down the page.Why? is always an important question to ask with a man as practical as Thomas Cubitt.The current hypothesis is that Cubitt was creating his grand works and wanted no man to be his master.Cubitt therefore built a tramway to the nearest chalk that was available proximate to his lands.The chalk was on the far side of the Rochester Road to the works so that the tunnel/bridge under Rochester Road /Pilgrims Way was required for the tramway to access it.

It was then, likely, realised that whilst this grade of chalk was perfectly fine for the making of bricks, it was too inconsistent for the making of high quality cements. This is because mixed chalks were not suitable for making consistent cements, with the technology of the time, as mix proportions could not be dynamically varied with the technology of the times. Cubitt was well know for being a major supporter of batch testing of materials; this view is supported by many articles in The Builder.

This is, in part, evidenced from the working of the Petts Farm Pits on a later highway map [insert link to footway/bridge stopping up map] which shows the extent of the quarry distinctly from the cutting. This would have made zero sense at a later date when the massive Great Culand Pits were active and even trying to work it concurrently with the Great Culand Pits would like have caused more issues for tiny extra volumes of production.

With better survey works it was realised that the better quality chalk was actually around the Great Culand Pits. However, the chalk is much further up the hill.

In order to understand what the tunnel was a requirement to increase efficiency it is necessary to understand something of chalk mining techniques of the time.

Chalk Quarrying

Chalk quarrying was carried out by gravity in an era before steam shovels. Chalk being a soft material could be hand quarried: men would descend the slope of the chalk quarry held by ropes from the top of the escarpment and use crowbars to displace the chalk which then descended by gravity and was directed, by timber staging and chutes, into the wagons below which were brought to the chalk face on railway tracks that were extended piecemeal as the workings were enlarged.

Below is an example with the wagons brought in alongside the working chalk face. The photograph shows how dangerous this operation was but if well set up how efficient it could be.

However, this necessitated the railway wagon to be at the lowest level of the chalk workings to feed into them by gravity.

A false colour LIDAR image of the old Burham chalk pits clearly shows the method of excavating and it is relatively easy to even see when the railway tracks were set out. LIDAR [Light Detection and Ranging] is a remote sensing method that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser to measure ranges [variable distances] to the Earth from a satellite. The false colour in the image helps to make the changes in contour clearer. The LIDAR image clearly shows that the working method was similar to Grays quarries.

How Does the Rail Tunnel Help With This?

Railways were the internet of the 1840/50’s and a sign of modernity in any plant. As was steam power and steam traction. Cubitt was a significant investor in railway stocks.

Given that it is necessary for the railway wagons to be at or below the lowest levels of the suitable grade chalk that were to be recovered a means of creating access through hillside which

- crossed ground that did not belong to the works; and

- contained, possibly, unsuitable grades of chalk to be worked for cement with the technology of the time; and

- was on a relatively flat route given the low engine powers of the time

a tunnel was likely the most efficient means of accessing the desired stratum.

The drawing [below – which is in the process of being redrawn, to to remove the references to the ca 1900 track layout to giving access to Little Culand Pit], does give a very clear view as to the commercial rationale for the construction of the tunnel to produce a relatively flat route to access the higher quality chalks to the rear of the site. A cutting would have been a huge materials shifting operation that would have taken the fields above out of agricultural production as well as generating an enormous mass of low grade chalk of precisely the kind that had, presumably, been determined as being of little use for cement making. This was likely a consideration in the costs analysis at the time.

[There are some erroneous assumptions in the original article about lands ownership and it wrongly states that all of the lands were owned – whereas it can, likely, be demonstrated from the sequence of the deeds that this was not the case].

Cubitt clearly had a substantial intent for the scale of the works. He was grumbling in late 1853 that the works were not finished and ready to be viewed, which indicates that something other than simply building big sheds was going on and he would in his slightly control freakish vertical integration way have wanted to control the supply of chalk to the works. Otherwise, he could easily be held to ransom by his competitors both on supply and price. As the scale of his works was significantly larger than his neighbours and he had a monster development at Pimlico to feed with huge quantities of bricks and lime as well as potentially suppling his brother William’s massive civil engineering business.

The tunnel under Rochester Road is likely earlier than the main tunnel. They are build to slightly different ruling gauges [width and height of trains they can take] with the 1/2 mile tunnel actually being wider than the Rochester Road tunnel at mainline ruling gauge of the time.

The tunnel itself is unusually wide and well constructed for a simple works tunnel. It has been suggested, by Fletcher and Down [Burham Cement Works, The Industrial, No 156, 2016 pg. 268], that it is one of the longest works tunnels in the cement industry.

Both William and Lewis Cubitt were experienced railway contractors. They had constructed the line into Euston which included plenty of cuttings and tunnels so the construction of a half mile tunnel through pretty stable chalk would not have been a major challenge to them. They had also constructed a cable hauled system out of Euston to enable the low powered engines of the time to get up the gradient to Camden. So brotherly conversation could easily have covered the construction of this system.

So the hypothesis is that the 1/2 mile tunnel was planned or started but maybe not finished in Thomas’s lifetime.

Dating the Tunnel

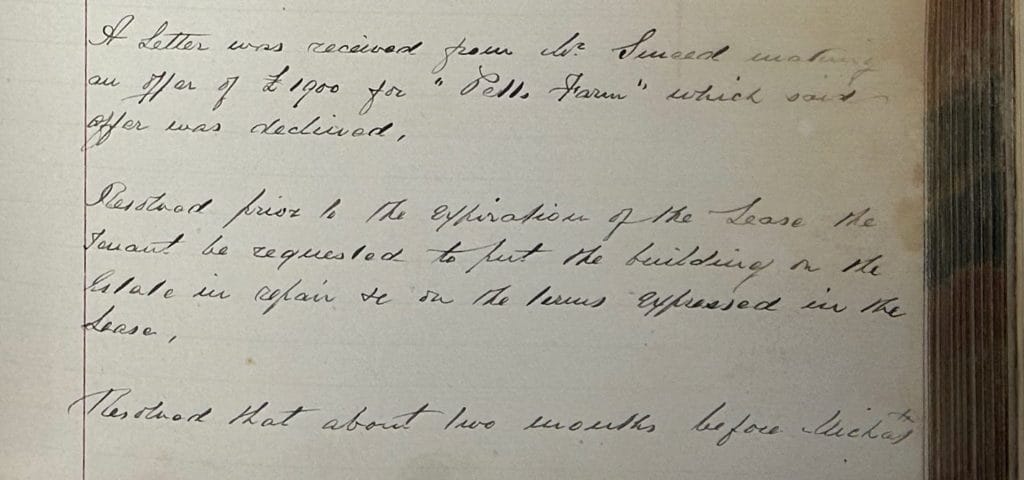

In a minute [Medway Archives, LBG/1] dated 27th April 1876 ‘A letter was received from Mr Smeed making an offer of £1900 for “Petts Farm” which said offer was declined’. There was a discussion of the offer and it was resolved to either sell the freehold or to lease it for 7 or 14 years when the tenants lease ran out.

This is interesting as it was ultimately sold to The Cement Company for £1350 [check that this is accurate] which is suggestive of either a decrease in land values or that a portion had been sold prior to the main deal or that that the easement for the cutting and tunnel had devalued that lands.

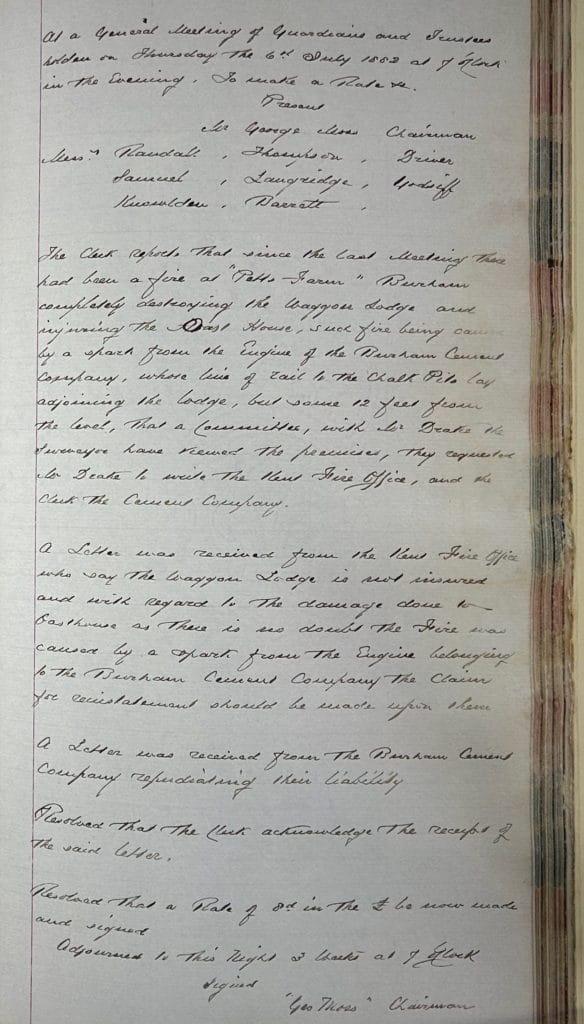

It is absolutely certain that the railway/tunnel and chalk pit were in full operation as a minute dated 6th July 1882 states that the Lodge & Oast Houses of Pett’s Farm were burned down due to a spark from the Engine of the Burham Cement Company whose line of dial to The Chalk Pit lay adjoining the lodge but some 12 feet from the level.

It could be significant that the minute specifically refers to the Burham Cement Company. It is possible that this indicates that the cement works were in different hands to the brick works.

This is very significant as it would imply that there was a prior agreement to either sell or grant an easement for the constitution of the tunnels and cuttings across the lands of the Charity.

The Pett’s Farm Oast houses extant today are directly beside the now flooded tunnel.

As there is no mention of any arrangements with The Cement Company, in its various guises, re Petts Farm in LBG/1, which spans 1869 to 1885, prior to Mr Smeed’s letter of 27th April 1876 it is suggested that the agreement between The Charity and The Cement Company, in its various guises, predates this. In the alternative there could, of course, be an omission in the minute book. Given the significance of the asset this seems unlikely.

In an almost illegible minutes of the 13th March 1893 Finance Committee meeting of the Board of Guardians [Medway Archives, LBG/2] a solicitor, Mr George Cossad(?) writes offering £34 per annum for Petts Farm. The minute appears to continue that the farm is to be advertised for disposal.

A further partially legible minute of 19th July 1893 appears to record various surveyors contacting the Finance Committee of the Board of Guardians re the disposal of Petts Farm [Medway Archives, LBG/2].

The purchase sum of £1,300 from The Burham Cement Company and the investment of the proceeds in Consols was subsequently agreed at a meeting of the Finance Committee of the Board of Guardians held on Thursday 7th(?) June 1893. The legibility of the entry is again poor [Medway Archives, LBG/2].

The sale of Burham Farm [note the change in naming] was recorded as completed in a minute dated 19th July 1894 [Medway Archives, LBG/3].

The changes in naming are suggestive that deeds may have been produced and filed under other names in various archives – making finding them considerably harder.

It is clear that a number of researchers, in eluding this one, have been mislead by the title containing Burham and the missing volume of the Burham Parish records. However, the relevant area of lands is in Aylesford Parish and those records are extant. It is possible that the minute book may record the necessary permission to create the tunnel under Rochester Road – the catalogue extract [Kent Archives P12/8/1] certainly mention permissions for other works tunnels and bridges.

The tunnel must have been in operation considerably prior to 1869 as Great Culand Cliff Hydraulic Line was being advertised for sale in Building News – Friday 23 July, 1869. That advert appears to confirm that the works for brick, lime & cement were united under one company.

[Further work – Medway Archives – Burham Parish minute books may give an indication of the permission to put the railway under road – however the 1850-55 book is missing]

Who Built the 1/2 Mile Tunnel & Why?

There are currently three contenders for whom built the tunnel as well as the obvious William Cubitt.

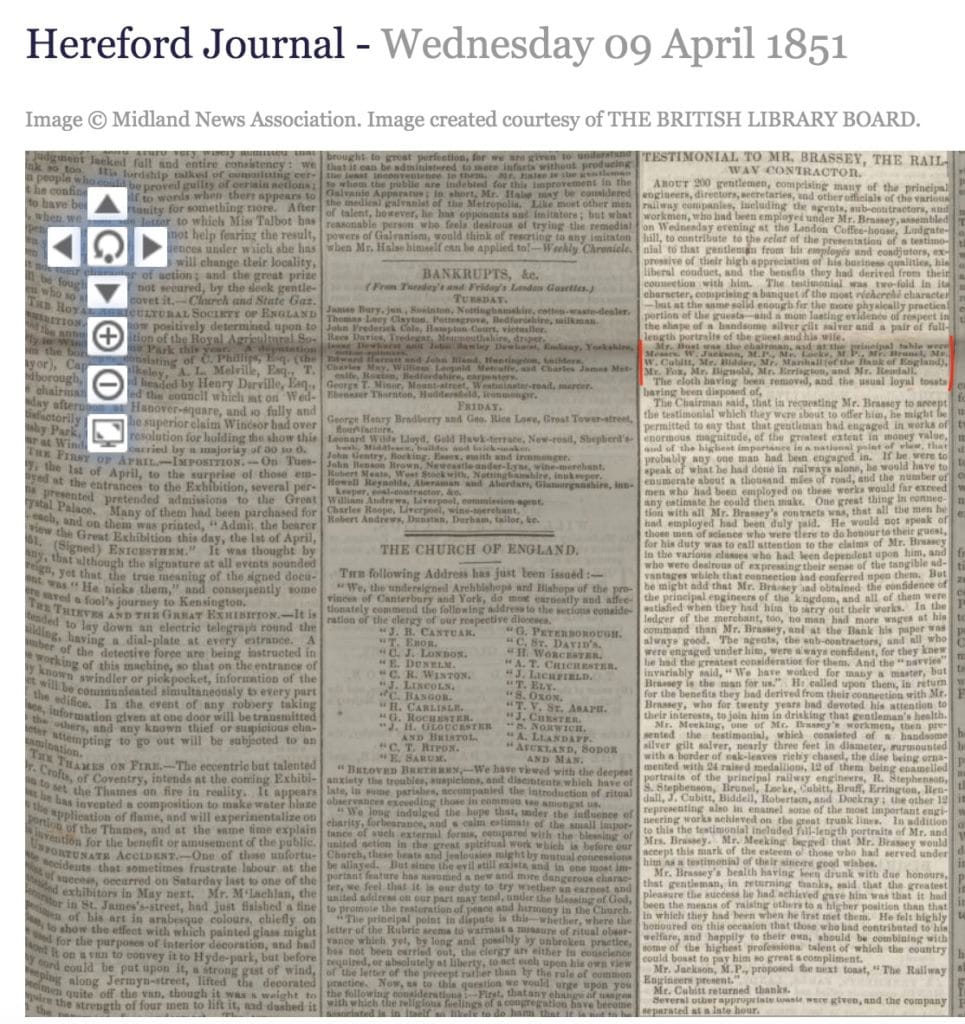

Firstly, research carried out by Martyn Fretwell [who runs the site UK Named Bricks] has lead to identifying Thomas Brassey, railway contractor born 1806, died 8th December 1870, as a likely contractor for the build of the tunnel. He at least knew William Cubitt and he later settled in the area running the nearby pottery works. Perhaps the tunnel was his introduction to Kent?

Brassey had bought 56 Lowdnes Square from Thomas Cubitt, 17th April 1847, for the sum of £4,400 and a rent of £55.

Thomas Brassey was, for sure in contact with Thomas Cubitt as this letter of 29th October, 1850 [below] shows. Some of it is barely legible as unfortunately the wet pages shifted during the process and it is effecting double imaged.

Book on Brassey’s life and works https://ia601205.us.archive.org/23/items/cu31924050092604/cu31924050092604.pdf

Secondly, consideration, also needs to be given to the Burge clan. Thomas worked with various Burge’s at the Calthorpe Estate and later in building up the Pimlico ground with the arisings from the St Katherine’s Dock which was built by George Burge. Burge was a major railway contractor and was famous for the Box Hill Tunnel which he built with Isambard Kingdom Brunel. He lived at 19 St. George’s Terrace. Herne, Kent in 1851 [1851 census] which is around 35 miles from the Burham tunnel.

Burge’s connections with the cement industry are well established. Source https://www.cementkilns.co.uk/bio.html “George Burge Snr (b 15/8/1795, Clerkenwell, Middlesex: d 2/5/1874, Margate, Kent)……

In 1850 he was approached by I C Johnson to enter partnership to construct the Crown cement plant. The partnership only lasted three years after which Johnson moved to the Cliffe Creek site. Burge put his son in charge, and continued with his railway contracting work. Probate £1,200 (£170,000).

George Burge jr (b 1832, Brixton, Surrey: d 28/9/1911, Herne, Kent) was a cement industry pioneer. He learned cement manufacture from I C Johnson, and was put in charge of the Crown cement plant by his father in 1853. He chose to concentrate on cement manufacture. He re-instated the failed Wouldham Court plant in 1855, but gave up on it in 1859. He sold the Crown plant to William Tingey in 1868, but collaborated with Tingey to construct new plants in the Medway area, while controlling their raw material supplies. He developed a design for a chamber kiln, probably in collaboration with Johnson, at the Crown site.

During 1874-1888, he built and expanded cement plants virtually on a production line basis. In 1874, in partnership with William Morgan and C R Cheffins, he established the Gillingham plant using his own chamber kiln design. In 1877, he converted the Phoenixplant for cement production. In 1880, he built the Globe plant for J C Gostling, and the Beehive plant, which he ran himself. In 1882, he went into partnership with F C Barron and built the Falcon plant. In 1884, he built the Beaver plant for Slark and Jones, and in 1885, the Bridge plant for T C Hooman & Co. Finally in 1888, he built the Quarry plant as a branch of his Gillingham company…..”

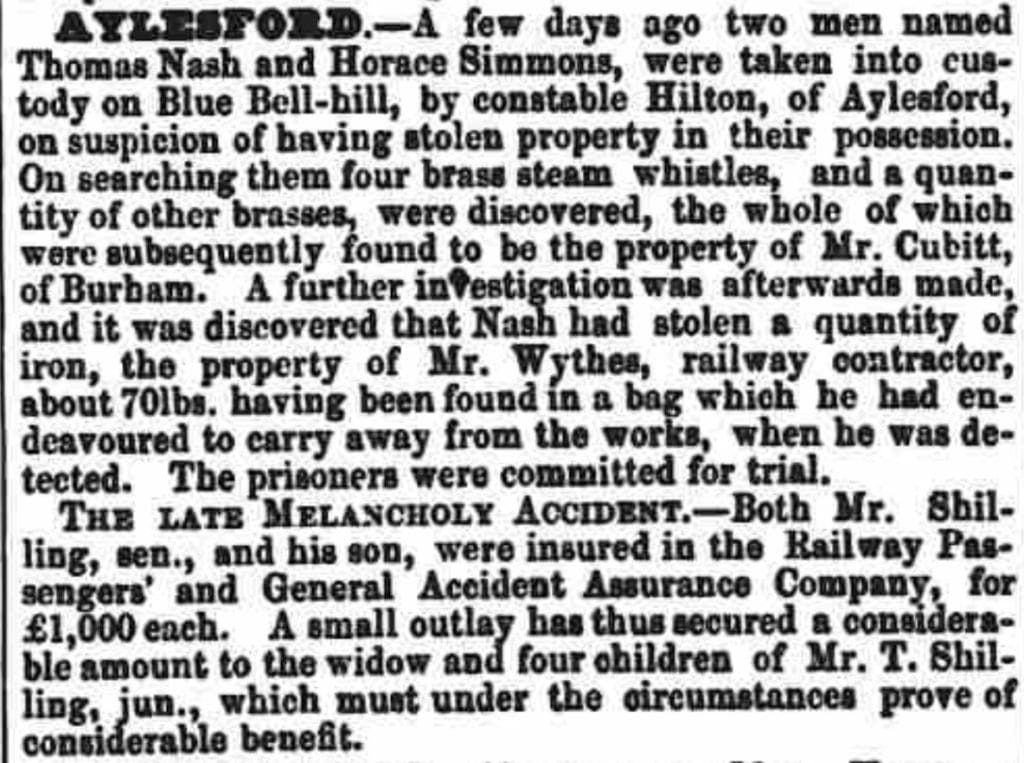

Thirdly, in the frame is George Wythes – his connection with the works is established via a report of a theft carried in the South Eastern Gazette [below]. Wythes was also had a documented partnership with Thomas Brassey. Wythes lived at Bickley Hall in Kent about 30 miles from Burham. Further Wythes was contracted to build the Maidstone railway shortly prior to this and so would likely have had teams to hand on the other side of the river.

An entry in South Eastern Gazette, dated Tuesday 12th December, 1854 confirms that Wythes was the contractor on the Maidstone – Strood mainline extension.

It would appear, from the letter of 14th November, 1859 from Andrew Cuthell to William Varney below, that Mr Wythes offered to buy the site from Thomas Cubitt’s Executors and Trustees. Possibly because he was already well acquainted with the site and it would have been useful to have a source of bricks and cement for another project?

[Wythes involvement in brick making can be seen

Bromley archives

License to use patented Inventions in the mode of Manufacturing bricks

Insert section here on the Cuthell to Varney letters offering more funds if needed .

What were those funds needed for if the brickworks were in the hands of Prall and Smeed?

Why indeed was Varney still there as Smeed and Prall were running the brickworks and William Webster had the cement works?

Why was Varney reporting to Cubitt Ho still?] .

It is seems that it was run under the W. Cubitt banner as this letter from William Peters makes very clear that Cubitts had, ‘extensive brickfields and potteries in Burham, and Portland cement works in the parish of Aylesford; but he is not on of the Medway limburners, nor has he any limekilns in Burham.’

However, the phrasing may be a tiny bit disingenuous as the massive works straddled the Aylesford and Burham boundary. Peters appears to be ploughing a particularly narrow furrow in the definition of Burham as a locality. So it is possible that they was lime burning on the same site on the Aylesford side of the works!

As an aside, it is very notable just how much of Thomas’ empire was so rapidly dismantled after his death. In the case of the brick and cement works it is probably indicative of its relatively poor location, size and the need for continued substantial investment. There is another factor that could well have played a significant part – most of the output of the works went to Cubitt’s Grosvenor Warf by barge. As the Grosvenor and Pimlico projects progressively wound down, due to completion, the utility of having a works that was centred around barge shipping would have significantly declined. The works was also not connect to the railway which was on the other side of the Medway.

- 1852-1855 Thomas Cubitt and Co.

- 1856-1859 W. Cubitt and Co – presumed this could have run on later on the cement works side possibly to 1862.

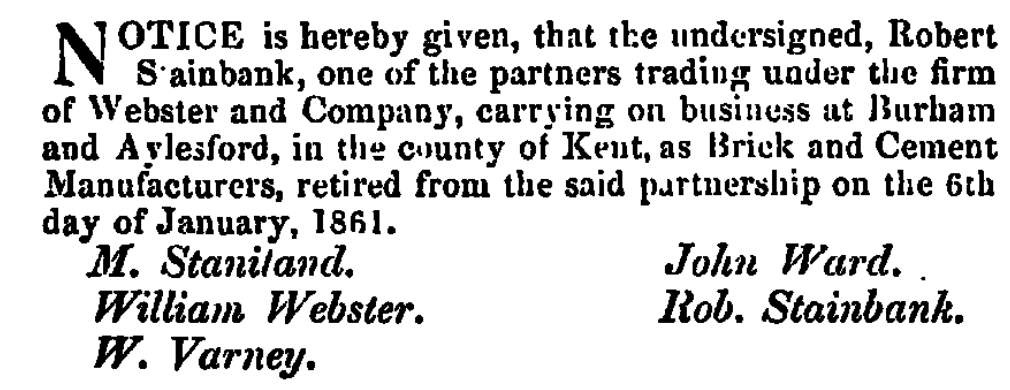

- 1859-1871 This appears to have been a complex period of operation with Webster and Co alongside Smeed & Co with the brickworks possibly operated separately from the cement works for some of this period of time. The 1860 conveyance to Smeed and Prall solely of the brickworks on the Burham side the site but then Agreement dated 1872 [click for full PDF] contained in the company formation files for Burham Brick, Lime and Cement Co. Ltd in The National Archives [BT 31/1670/5913] and the various intervening partnership variations in The Gazette.

- 1871-1900 Burham Brick, Lime and Cement Co. Ltd [click link for PDF] – company formation files The National Archives [BT 31/1670/5913].

- 1900-1938 APCM (Blue Circle) – Burham Brick, Lime and Cement Co. Ltd company voluntary liquidation file [click for PDF] in The National Archives [BT 34/88/5913].

An, unsuccessful, attempt seems to have been made to sell the works as early as 1857. A new partnership was formed to run it in 1859 – it is far from clear that the works was actually sold as opposed to simply got off W. Cubitt & Co’s books.

The idea that the works was simply got off the books is reinforced by the following sentence in an article in The Atlas, Saturday, August 20, 1859, which states;

Since that gentleman’s death, and the completion of his Pimlico operations, the works have been offered by his executors for sale, but so gigantic are they, that no one firm have been able to grapple with them, and a company is now formed, under the name of the Burham Brick, Pottery, and Cement Company, to purchase work the property under the Limited Liability Joint Stock Act.

The key words being to purchase work the property which implies that that Cubitt’s executors would be paid a proportion of the profits rather than an outright purchase price.

Add in images of the key letter from the letter books.

Cubitt -> Bailey – Cubitt Letter Book A 263-4 4th June 1851

Cubitt -> Whitbread – Cubitt Letter Book A 272-3 19th June 1851

Cubitt -> Whitworth – Cubitt Letter Book C 168 & 296 24th Jan 1853

The Post Thomas Cubitt History of the Works

1856 – Decision not to Sell the Cement works.

Andrew Cuthell wrote to W. Jeffery on 28th January 1856, [Bk. V Pg 105] I have talked over the Subject of the Cement Works with the Executors and it is determined that no change shall take place for a year or two respecting them, but that we shall go on as we are….

1856 – Decision to Sell the Brickworks

In a letter dated 20th September, 1856 Andrew Cuthell sets out to H. A. Hunt that a decision to sell the brickworks had been made. Interestingly the value of the expenditure of the works is given as £54,000.

1856 – Interest in the Brick and Pottery Works

In a letter dated 14th January, 1856 to G. R. Booth, Andrew Cuthell states, “…..I beg to say that you have been misinformed regarding the Burham Brick + Pottery Works. However, should you have any proposition to offer to the Executors on the subject of your letter…..should have attention…..”

G. R. Booth was from a well known pottery family and was married to Jane Ridgway who was the daughter of George Ridgway of the famous pottery clan.

1859 – Attempted Sale of the Brickworks

It is assumed, from tangential references, that the plant was run under the W. Cubitt banner from the death of Thomas in December 1855.

When the works was put up for sale seemingly around 1857, the following plant and machinery was included: ‘2 steam engines of 110 horses each and 4 steam boilers; , double brick machines in line of Sheds, machinery in large Tilery building, Machinery in old Engine House near Clay pit, shafting, two Steam Wash Mills, pipes for……Cuthell to Chas. T. Lucas, 4 February 1857, E. 248.

There really interesting part of the letter that Cuthell wrote to Lucas is that Cuthell puts a value to the works….and also talks specifically about the Brickfield Estate.

I send to you on the other page a small plan (perhaps not quite to scale)

Shewing the Boundary of the Brickfield Estate at Burham and Aylesford

but the plan does not include 12 acres of the Larkfield Estate for Sand Pits which are included in the Terms —

The Price I named of £40,000- / or £10,000 & £1,500 pa Rent

So it is very clear that, likely just, the Brickworks were for sale for £40,000.

Fortunately, the little sketch drawing is also pasted into the letter book and survives, imaged below. However the manuscript annotations are so smudged as to be indecipherable. However, the cement operations do appear to be coloured differently, which further suggests that they were not included in the proposed sale to Chas T. Lucas.

By June 1858, Andrew Cuthell signs off a slightly more realistic appraisal of the value of the works had been made. However, it is unclear if this value relates solely to the brick and tile works or includes the cement works.

The letters below make it clear that the intention, at that point in time, is to grant a long lease for the £40,000 and not to sell the freeholds until the £40,000 is paid up.

Presumably, having set out acceptable terms, Andrew Cuthell writes to Fuller & Horsey leaving the matter of negotiating with Mr Parker of Islington to them.

8th September 1858 marks the point where Andrew Cuthell writes to W? Morris that ‘I am sorry to tell you that we do not propose going on with the works at Burham – & the account keeping will be reduced to little or nothing – under the circumstances we shall not require your services boys a month…..’

It is tempting to read this as works rather than work. Henry Morris was a surveyor. So it is just possible that the ‘accounts’ being written of in the letter below actually as contractors accounts/valuations for the development of the works/railway system.

An interesting schedule of equipment and provision is listed in the Morning Herald, Friday 29th October, 1858 [below].

It is worth noting that the advertorial does talk about the pits being formed near the summit. These are likely chalk pits, as there are no significant clays at the summit, as the operation of the cement works is described.

The lack of success can be ascertained from the exact same wording being printed every month in the London Morning Herald [and other papers] – thought to Friday 29th October, 1858.

Andrew Cuthell, 29th January 1859, writes to Fuller & Horsey that ‘….his [Mr Connor’s] offer could not be entertained in its present form….’ but does go onto suggest ‘We shall be willing to make some reduction, but I quite agree with you that it will be time enough to lower the price when we get a bona fide offer…..’

It would appear, from the letter of 14th November, 1859 from Andrew Cuthell to William Varney below, that Mr Wythes offered to buy the site from Thomas Cubitt’s Executors and Trustees. Possibly because he was already well aqunaited with the site and it would have been useful to have a source of bricks and cement for another project?

The Burham Brick, Pottery & Cement Company – 1859 – Abortive

The expectation of Thomas Cubitt’s Executors and Trustees to sell the works is very clear from the letter below ‘….little doubt that the new people…’ presumably the new people were to have been the putative Burham Brick Pottery and Cement Company that never got off the ground? Or may well have been others identified as interested parties.

It may be that this letter from Andrew Cuthell [below] relates to a pause in advertising as The Burham Brick, Pottery & Cement Company attempted to form a fully subscribed company. There is mention of a Mr Connor in the advert for subscribers below, so it is possible that Mr Connor was a part of another syndicate bidding for the works.

Letter from Andrew Cuthell to James Hopgood updating him on a visit from Mr Connor & Mr Payne and their intention to draw up draft proposals for the purchase of the Burham Works.

Mr Payne’s proposal for the Brick & Cement works at Burham is rejected and the negations duly terminated.

There was then an attempt to form a company, The Burham Brick, Pottery & Cement Company, with a working capital of £100,000 – this was a quite enormous sum for the time. Given how little Cubitt had paid for the lands there is more than a suggestion of disproportionately heavy investment in this huge sum of monies that Cubitt’s trustees clearly desired for the works.

Clearly this is well above the £40,000 that Andrew Cuthell was suggesting to Chas T Lucas back in 1857 [above]. This is suggestive of either massive investment in the intervening period or a spectacular overvaluation of the works. Or something else.

Before drawing any conclusions it is worth of note that one of Thomas Cubitt’s direct descendants, Sir Stephen Tallents, put the capital investment in the plant at £80,000 – so either that is erroneous or substantial monies were invested in the plant between 1857 and 1859.

It would appear, from the letter of 14th November, 1859 from Andrew Cuthell to William Varney below, that Mr Wythes offered to buy the site from Thomas Cubitt’s Executors and Trustees. Possibly because he was already well aquainted with the site and it would have been useful to have a source of bricks and cement for another project?

This seemingly failed as stated in this clipping from The Times [below].

The wording of the Morning Advertiser article of Saturday 6th August, 1859 is quite suggestive of simply getting shot of the Burham site as fast as possible as Thomas Cubitt’s trustees had no interest in it whatsoever now that all the major Cubitt developments, such as Pimlico, were drawing to a close and the scale of the business was reducing.

Most satisfactory arrangements have been made with the executors of the late proprietor for the purchase of……at a cost of half of the original outlay…..while even of this sum a large proportion…..remain on mortgage at the usual rate of interest.

This is also suggestive of over investment into the site.

Given the article in the The Atlas, Saturday, August 20, 1859 uses the phrase to purchase work the site then it is reasonable, as a starting assumption, to presume that the mortgage was provided by Cubitt’s trustees.

There is a very full account of the works in, The Illustrated News of the World, on 8 October 1859. This needs to be taken with a judicious pinch of salt as was almost certainly instigated by the new owners. But it does state that there were upwards of three miles of railway and tramway in the works. It is quite hard to see how a three mile layout was achieved without the line to at least the Culand Pit cutting [the cutting between Rochester Road and the half mile tunnel] having been created.

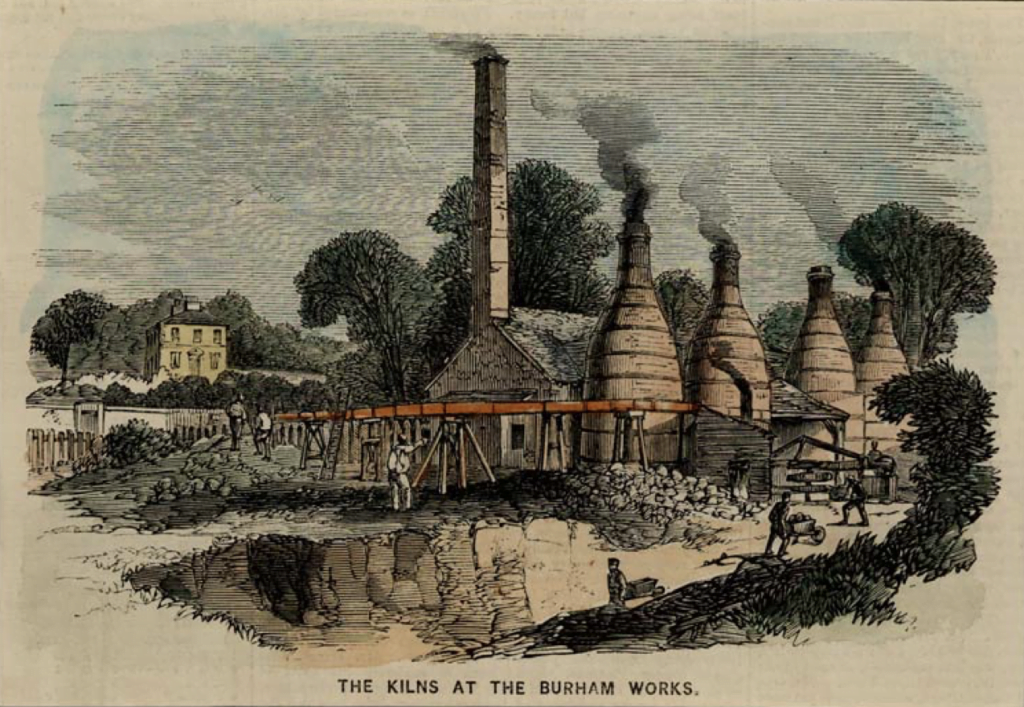

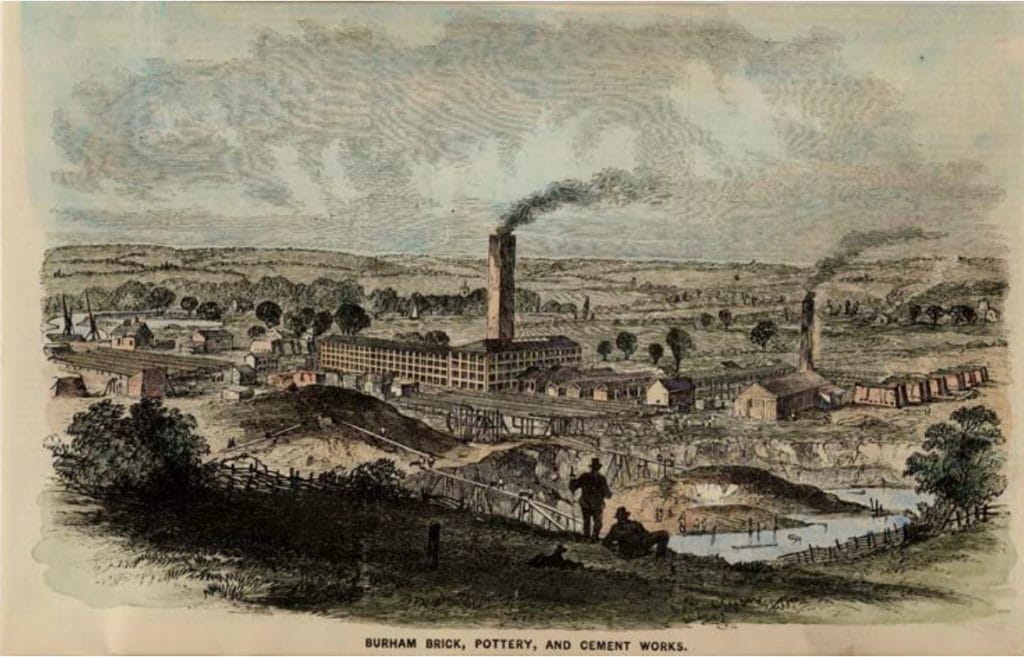

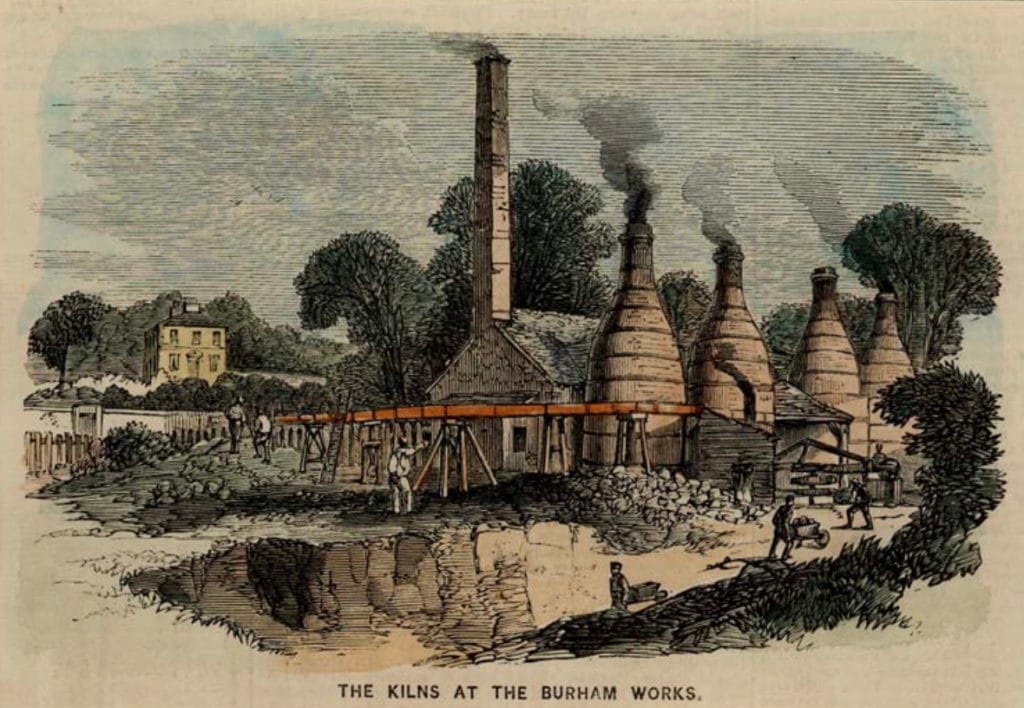

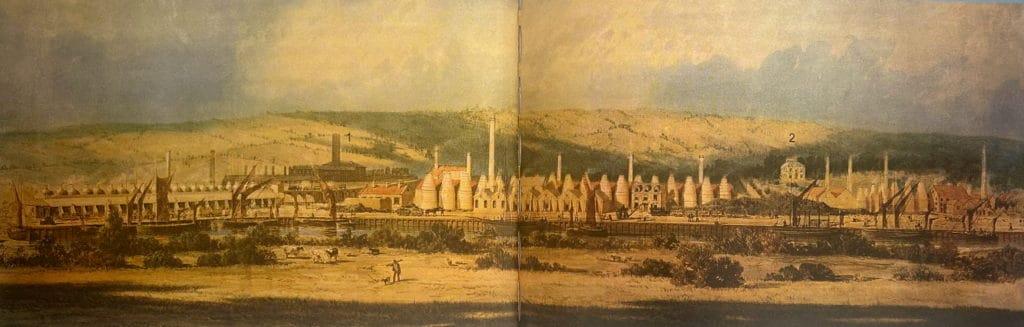

“We present our readers, on this page, with two engravings illustrative of these extensive works. It is well-known throughout the building trade that the late Mr. Thomas Cubitt’s works at Burham produced the very best bricks and pottery ware that could be profitably brought into the London market; and that the whole establishment, under the superintendence of the present manager, has arrived at a degree of perfection which will render it very difficult for any other brick-field in London to compete with that at Burham in respect of prices. In order to give our readers an idea of the extensive nature of these works, we cannot do better than lay before them the following account furnished by a gentleman who has visited this establishment. He left London one morning, by the 10.15 North Kent train, and arrived at Snodland in two hours. “On the journey we passed,” he says, “many brick-fields of various extent, and after passing Strood they became more frequent, but in none of them did we see more than is ordinarily to he seen in such places. After passing Cuxton, the Wouldham and other cement works were pointed out to us on the banks of the Medway, and immediately after, long before our arrival at Snodland, we saw the large pottery and engine house of Burham, with its immense square shaft rising up in the valley, and reminding us very forcibly of the large building on the banks of the Thames at Pimlico, so well known as Cubitt’s workshops, and now in the occupation of the Government.

On alighting at Snodland, we crossed the Medway in a ferry boat, and after a walk through the fields of about mile past the old church of Burham, we arrived at the works. The first objects of interest that attracted our notice were numberless rows of little sheds, under which the bricks are dried and which are termed hack grounds. These little sheds, about six feet high by three and half broad, cover upwards of seventeen acres of ground, and are situated between the brick machines and the kilns, and are intersected with lines of tramways. The whole estate is on a slope, falling gradually about one in eighty-five towards the wharf on the river, which fact considerably facilitates the economical working, as all the heavy material goes down hill, and in no case does any material or article have to travel over the same ground twice. At the top of the hill the clay is now dug, and is crushed and washed on the spot. The manager of the works, Mr. W. Varney, who was upwards of forty years in Mr. Cubitt’s employ, informed us that he had in the first instance selected the estate for Mr. Cubitt, and that the whole of the vast works had been erected and developed under his own immediate and residential superintendence. The clay is about 130 feet thick, and will last for a century to come. After being washed and crushed, the clay is conveyed in waggons or tramroads to the pugging.

mills and machines, where, after going through a very simple process of squeezing, squashing, and pressing, it issues forth from the various machines, through the dies, in the shape of bricks, either solid or hollow, and tiles of all sorts, sizes, end shapes. These are generated, so to speak, by the machines with a wonderful rapidity, and conveyed by boys off the machines on to harrows, in which men wheel them into the drying hacks, under which they are stored to dry, previous to being stacked in the kilns for burning. All the brick machines are worked by one long shaft, 520 feet long, which receives its motion from the large engine of 220-horse power. This engine we found to be an old friend, being the one formerly worked at the Minories Station to wind up the endless rope on the Blackwall Railway, when the trains on that line were propelled by the well-known wire-rope. This engine, which is by Maudslay and Field, does nearly all the work of the place—pumping water, crushing clay, flint stones, &c., working the pug-mills, and all the brick, tile, and drain-pipe machines.

The latter articles are all made in the large building forming part of the engine- house. There are four floors, 400 feet long, on all of which drain-pipes, ornamental flower and chimney pots, tiles, &c., are made and dried, the beat from the boilers and the pottery kilns being turned off from waste into various pipes and chambers for heating the rooms, and so drying those goods which are not suitable for out- door drying in the hacks, previous to burning in the kilns. The number of moulds and wooden frames to receive the several articles when first formed, and when the clay is still plastic and liable to damage by handling, is really surprising. To give some idea, there was one pattern for hollow tiles of which Mr. Varney informed us there were in stock 80,000. The more elaborate articles made in this building are burnt in the kilns in the building; but the stronger and coarser goods are burnt in the out-door kilos with the bricks, and from each floor is a tram-road down an incline for waggons, leading direct from the pottery house, with the goods when dry, to the kiln where they are burnt, and the manufacture is so arranged that the heavy goods are made on the lower, and the lighter on the upper floors, so that in loading (as it is termed) a kiln of dry goods for burning, the heavy and stronger articles are at hand for the lower portion, and the more fragile goods for the upper tiers. After being burnt, the goods then ready for market and use are drawn out of the kiln on the opposite side to where they are loaded, and are placed on trucks on the line of rails immediately contiguous to the kiln doors, and are thence conveyed down the gentle incline of about 1 in 85, either to the wharf, to be at once loaded into barges and sent away, or to be stacked on the stock ground to await purchasers. With the single exception of the coal which is conveyed from the wharf to the kilns and engine-house there is no up-hill traffic, and even this is considerably assisted by the down pull of the loaded waggons, which also, as they go down to the wharf, help up the empty waggons back to the kiln. Thus much horse labour is done away with, and, instead of a large stud, only a very few are requisite to do the work. Some idea of the completeness of these carrying arrangements may he arrived at by the knowledge that there are upwards of three miles of tram and railroad on the works, with numberless turn-tables, weighbridges, etc. Nothing here is wasted; all the broken bricks, drain pipes, and even what few stones there are in the clay, are ground up to powder in a powerful mill worked by the large engine; and on being mixed up with the clay, form a material out of which some superior quality of goods are manufactured. “A never-failing supply of water is obtained front the river, which feeds a reservoir of some three acres in extent; and at the wharf, which is of the most substantial description, and stone-faced, some six barges may be loaded at once. At high tide there are fourteen feet of water at the wharf. Adjoining the wharfs are the cement works, consisting of engine and house, washing mills, some four kilns, with accompanying drying stoves and nine coking ovens.

Nothing strikes a visitor to these works more than the substantial character of everything on the estate. All is of the most solid construction, perfectly unlike any other brick works we ever visited. In most cases a few boards roofed in with tiles, forming a tumble down looking shed, forms all the building one sees, except the huge square masses of burning bricks, called clamps. At Burham everything is made as if to last for ever—all is Cubittian in its appearance, and everything is burned in kilns of the most approved construction. In addition to the large engine—our old Blackwall Railway friend—there are three others of various power; and all the necessary workshops, with room for the men, foremen’s cottages, &c., are in their places.

Near the top of the hill is a most substantial house, indeed quite a mansion, which overlooks the works. This is the residence of the out-door manager, Mr. Varney; and on viewing the whole field, with its various and numerous engines, buildings, tramways, kilns, wharves, &c., one cannot but see that here are what may be justly termed the model brick-works. Here are concentrated the results of near half a century’s experience and improvements. Everything is in the right place. Nothing superfluous. Every possible attention has been given to economize labour and material, and every advantage taken of the natural position of the estate. When in full work, between 600 and 700 men and boys are employed, and from 25,000,000 to 30,000,000 of bricks, besides tiles and pipes, can readily be turned out from the works; which, however, can be considerably augmented without any great outlay, or increasing the present steam power.”

The transfer of the Brickworks to Smeed and Prall – 1860

Fletcher and Down [The Industrial No 159, 2016 pg. 261] state that there was an indenture dated 9th April, 1860 ‘from Cubitt interests’ to George Smeed and Richard Prall. The interesting part of this is that the indenture only seemingly covers the immediate area of the brickworks. This is suggestive of the site being split in operations. Given that documentation of The Burham Glebe Lands, is almost fully extant, it is possible to state that this indenture was likely an assignment of the lease or even just a license to work the site as the Glebe lease was not in fact in any way altered until it had fallen in [expired] and the lands were then sold on as a freehold to The Burham Brick, Lime & Cement Co Ltd [1871] – the date is added to aid disambiguation.

The deed plan drawing is extraordinarily similar to that shown in Hobhouses book with a presumed date of 1856. It is tempting to suggest the figure in Hobhouse’s book is from 1853/4 when the cement plant was first established – as can be deduced from the Aylesford Parish rating book as the cement works is rated in March 1853. It is a little unbelievable that with the vast sums expensed on the site that the cement operations had not changed significantly in the 6/7 years intervening.

Webster & Co – 1860?