Cubitt’s brick, lime and cement making

Cubitt’s brick, lime and cement making

[This page is an early draft and is in the process of being updated significant new information has come to light as of May 2025 and is being evaluated]

What motivated Thomas Cubitt to invest huge sums of money in developing a new brick, lime tile cement operations at a time when his existing projects were running down in volume and he had not purchased significant additional lands to develop?

The answer a likely a mixture of Thomas Cubitt:-

- needed to control the supply rate and quality of bricks so as to maximise build efficiency; and

- was so wealthy that he just could; and

- wanted to do it for a challenge [maybe to fulfil some of his boasts in The Builder]; and

- realised that his present main brick fields in Caledonian Road were exhausted; and

- knew that high class neighbourhoods did not appreciate having a dirty smelly brick field next to them; and

- was an ardent campaigner for cleaning up London’s filth air; and

- wanted to make contoured bricks and tiles without the labour intensive cutting and rubbing post processing.³

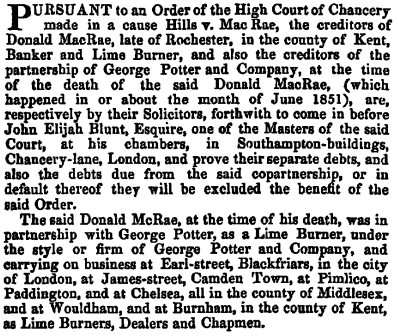

It is also possible that Cubitt was simply stepping in to fill the shoes of his existing lime supplier. It is unknown if the George Potter of Grosvenor Basin, Pimlico and Wouldham and Burhnam who was declared bankrupt on 23rd January 1852 was a supplier to Thomas Cubitt but it is quite the coincidence in timing. Equally, it is possible that Potter’s insolvency could have been caused by Cubitt’s setting up his own internal supply chain.

In Georgian, and prior, construction bricks were made locally to the development due to the difficulties of transporting such heavy weights and distant with a horse and cart. This lead to pretty unpleasant environments around such developments as brick fields produced plenty of soot and smells as the bricks were fired by burning a variety of unpleasant materials to increase the firing temperature.

Cubitt had extensive brick making activities on Thames Bank, using Aninslee Machines described in The Builder, 27th May 1843, pg. 195 [opens the full article]. He also had a major brickfield for excavating clays, then taken to Thames Bank, at Caledonian Road which was by the 1850’s exhausted and the land was by then also then valuable and desirable for development.

Hobhouse [Cubitt: Master Builder NY, 1971, pg. 307] suggests in relation to the wording of an article in the Illustrated London News in 1844 issues January 1845 [this reference does not appear to be correct as we cannot track the article down in the British Newspaper Library].

The article apparently stated:-

‘At length, Mr. Cubitt, on examining the strata, found them to consist of gravel and clay of inconsiderable depth; the clay he removed and burnt into bricks, and by building on the substratum of gravel, he converted this spot to one of the most healthy, to the immense advantage of the ground landlord and the whole metropolis. This is one of the most perfect adaptations of the means to the end to be found in the records of the building art.’

Hobhouse’s, very salient comment is:-

This passage, written in 1844, perhaps exaggerates Cubitt’s acumen in making bricks in Belgravia, which was being done at the same time by Seth Smith and other builders, but is worth quoting as an example of the growth of the Cubitt legend even in his own lifetime.

In that context it is, perhaps worth take note of the acerbic comment made by James Spiller, the Estate Surveyor, during the Calthorpe Estate development: he states in an office copy dated 5th April, 1819 ‘he [Cubitt] has however unduly excavated a part for the clay of which he has made many indifferent Bricks’.

Presumably, Cubitt improved his brick making prowess in the intervening period?

Price Albert purchased brick/tile making machinery for the estate at Osborne House from Thomas Cubitt, possibly having seen the write up in the Illustrated London News in 1844?

In the intervening years, since Hobhouse published her seminal work, a number of individuals have done substantial work on these areas.

The Genesis of the Burham Brick Lime & Cement Works

Cubitt owned, in the final years of his life, a substantial brickworks at Burham which then increasingly became a cement works.

In fact, it was only an operational brickworks under the Cubitt banner from 1851/2 to 1859 – such a short period of time that it was almost certainly not worth the management time or massive investment.

Cubitt commented in a letter of 1853 [reference required] that the site was not ready for visitors and so we can assume it was still be constructed and expanded.

Sir Stephen Tallents, in his autobiographical work [Man and Boy, Faber & Faber, London, 1943 pg. 35], asserts that Cubit spent £80,000 “in equipping” the Burham Works which were just completed when he died. This phrasing suggests that the purchase of the lands was on top of this investment in the plant. It is unknown where Tallents derived this sum from as he gives no references. Tallents was related to Cubitt and discusses childhood summers at Cubitt’s mansion, Denbies, in great detail.

Acquisition of the lands and existing works

There was probably a small limeworks and probably brickworks on or close to the site that Cubitt ultimately chose.

Cubitt’s was limited in his choice of locations as many of the best ones had already been taken. The two things that Cubitt didn’t lack at this stage in his business career were ready cash and ambition to scale.

Cubitt had already bought the Advowson to Burham, from a Colonel Milner, and this is set out in the First Codicil to Thomas Cubitt’s Will of 1855 and leased the Glebe lands which were close to the river Medway presumably for access to the river and wharfage. Seemingly he also owned some local lands as he exchanged these in his 1851 bargain with the Earl of Aylesford.

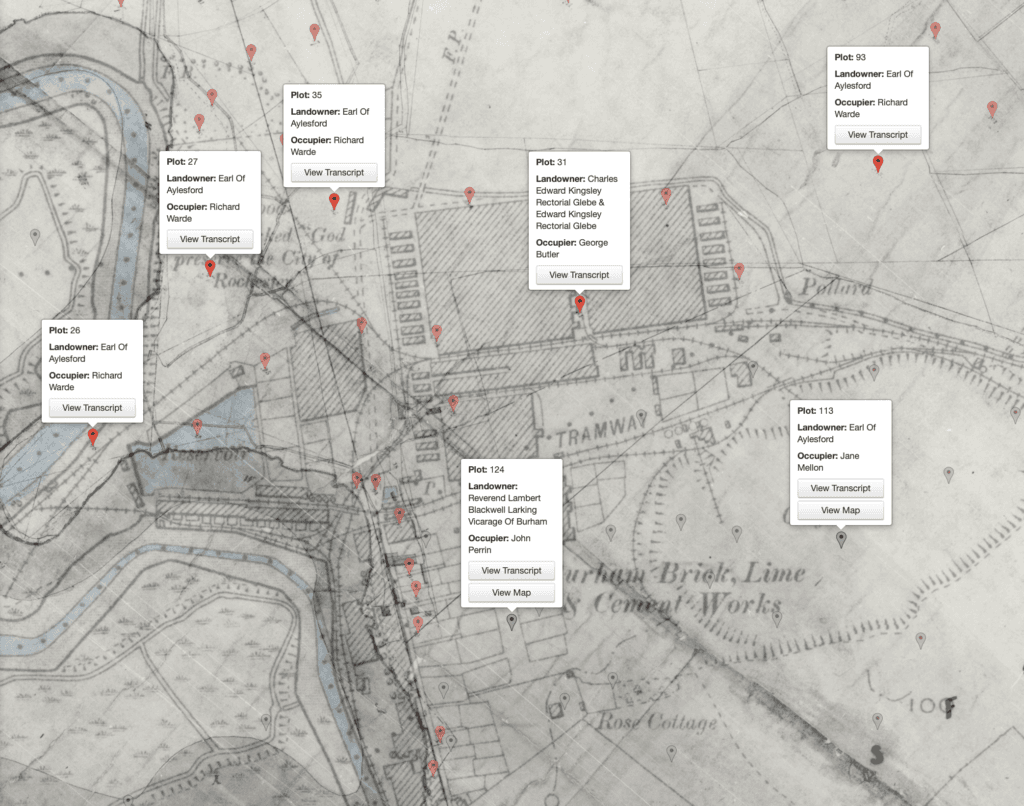

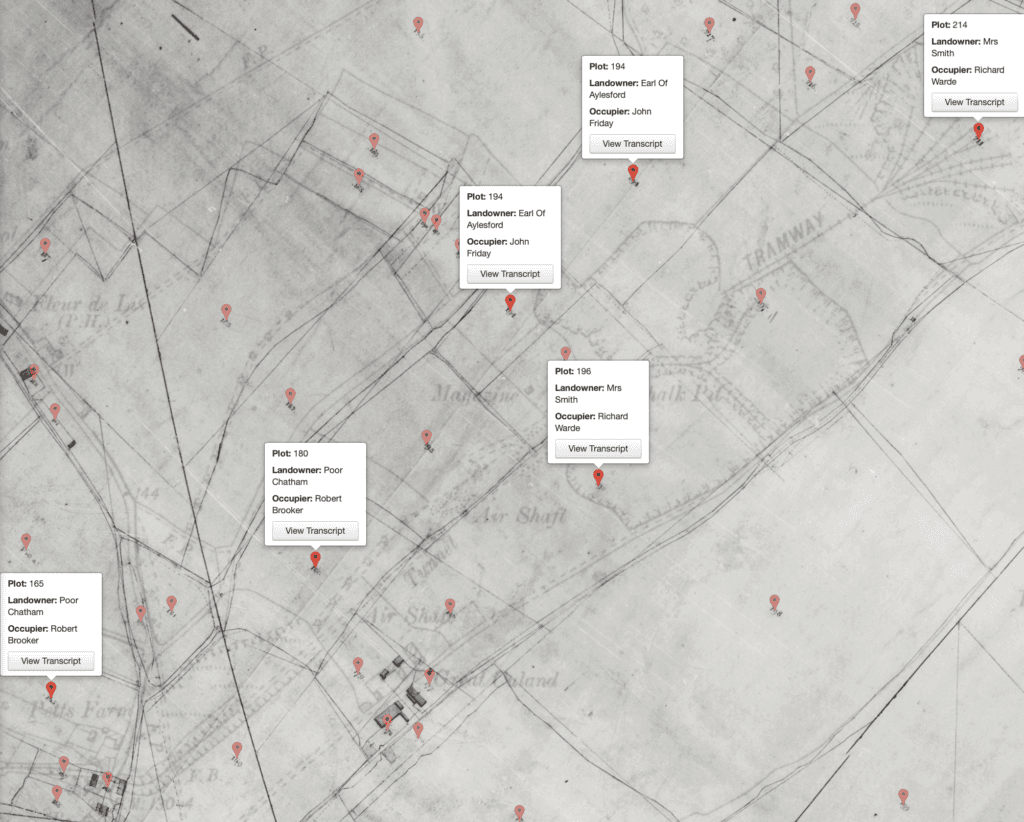

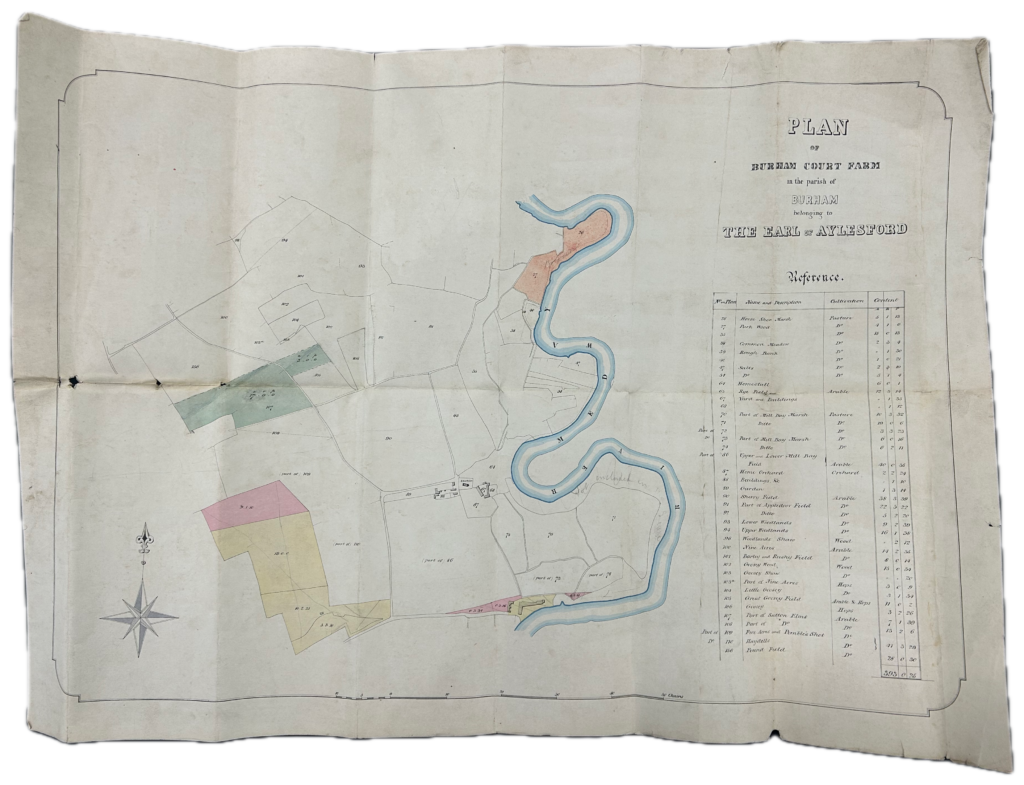

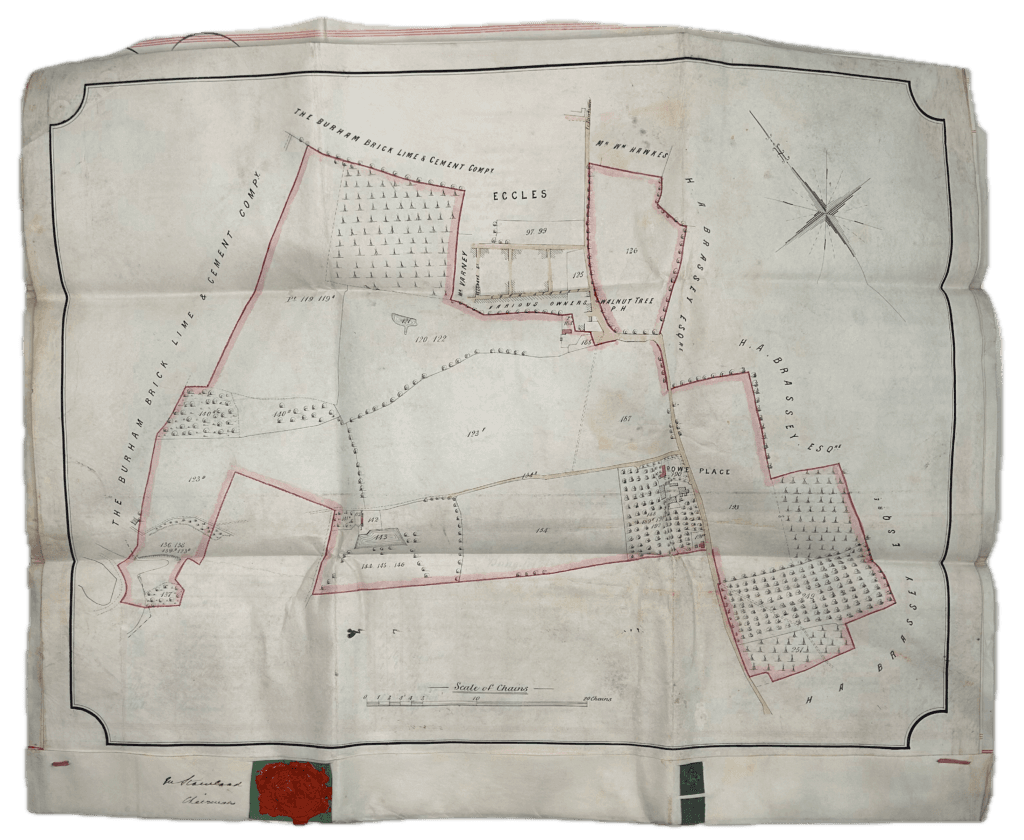

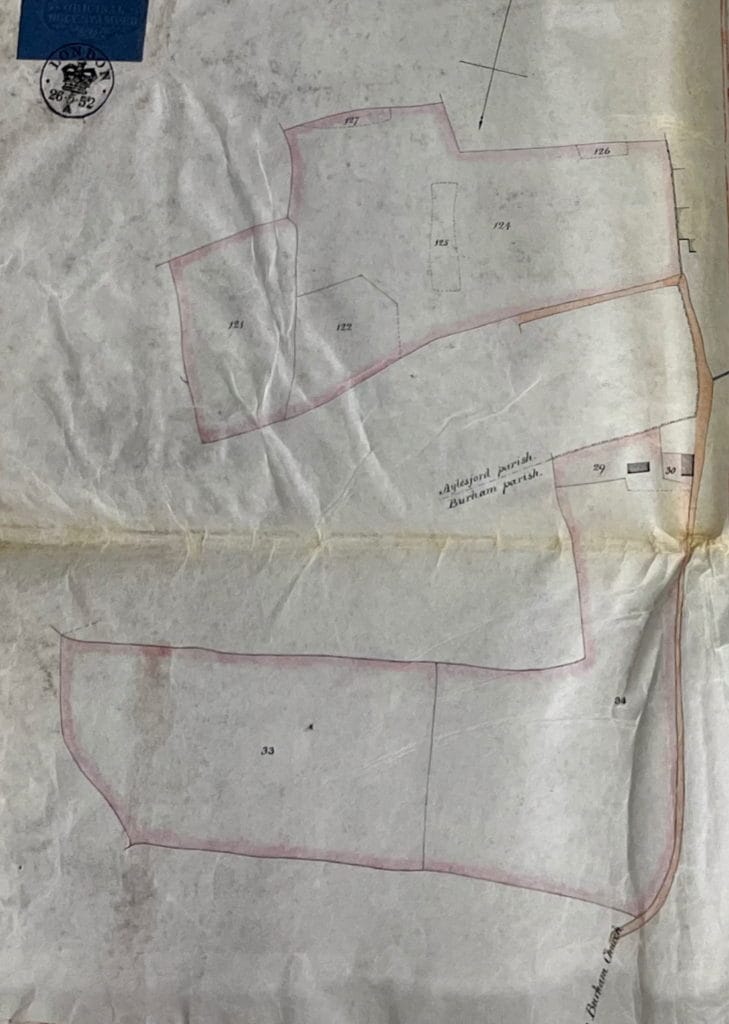

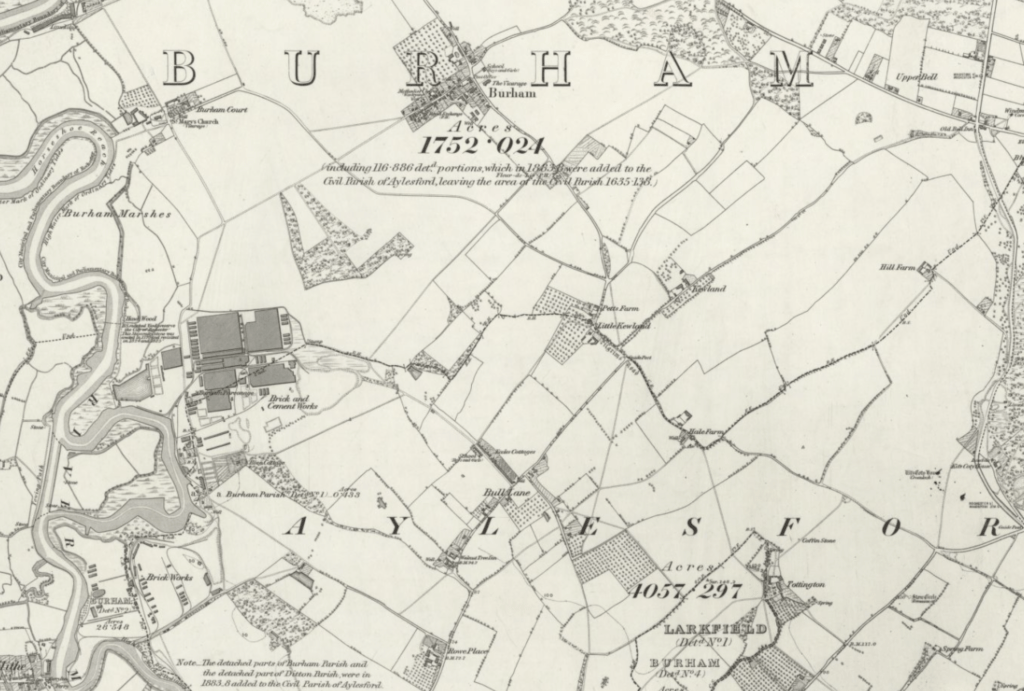

None the less, the site is made up of a highly complex mix of landowners; as these two overlay maps of the tithe maps with the early OS maps show. The working assumptions is that the works developed from a clay pit supplying a brickworks and then rapidly moved onto the self sufficient supply of chalk for the bricks, lime and cement operations. The scale of the chalk pits is absolutely huge and it testament to the volumes of material produced at the plant over its nearly 100 years of operational span.

Cubitt bought up various parcels of lands, all of these purchases are based on primary source documents that are sadly shorn of their deed plans;

- Earl of Aylesford – Lands in Aylesford being 2a.2r.26p [formerly with Ambrose Ward]; and 12a.2r.10p [known as Reed Hills] transacted ~29th September, 1851 – for the sum of £1055. Offset with a land swap of 9a.1r.23p of lands also in Aylesford. From a draft signed by Ja[mes] Hopgood p.p. Cubitt on 19th August, 1851 [Kent Archives U234/E4].

- Earl of Aylesford – Lands in Aylesford being being 9a.1r.23p, South West & North West of the high road leading from Aylesford to Burnham and Rochester. From a draft agreement to produce deeds dated, 26th February 1853. No consideration sum is stated. [Kent Archives U234/E4].

- Earl of Aylesford – two piece of land in the Parish of Aylesford being Rowe Place 12a.2r.10p and part of Burham Court Farm 2a.2r.27p by indenture dated 26th April, 1853. Stated in a statutory declaration made by Roland Bennett dated 19th March 1860. No consideration sum is stated. [Kent Archives U234/E4].

- Earl of Aylesford – copy indenture dated 27th April, 1853 – Burham Court Farm 2a.2r.20p; and 2a.2r.27p of arable lands; and 12a.2r.20p Reed Hill part of Roe Place Farm. Consideration sum £2,555 although this is crossed through with the word four annotated in pencil above it. However, the signature page states £2,555 which is unaltered. [Kent Archives U234/E4].

- Indenture of 25th June 1885, agreeing the terms of the mortgage of the Burham Brick, Lime & Cement Co Ltd, states that the sums paid were £395 2s 7d; and £3500; and £7,100; and £22,000 giving a total value to the lands purchased of £33,045 2s 7d although it doesn’t quite state that these were the Cubitt purchase sums but it is presumed that they are. The £22,000 would be an unbelievable sum in the 1850’s so it is suggestive that this was a later transaction, likely the 1885 transaction, when land prices has substantially inflated. [Kent Archives U234/T4].

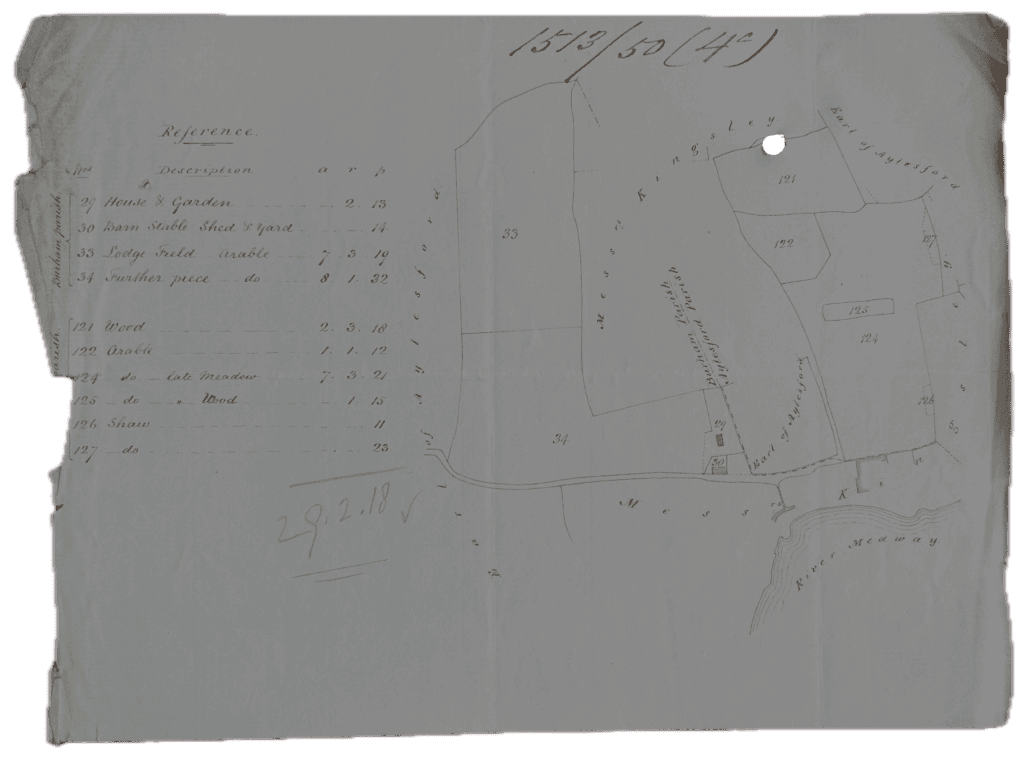

The Cubitt era deeds appear to be numbered with the tithe numbering it is possible to plot out what was bought when. The tithe numbering and maps were carried out in the 1840’s and so would have been close to current in the early 1850’s as the best official source of information to correlate deeds to.

Confusingly the auction catalogues appear to have used another lot numbering system: for instance the 1884 auction catalogue which marked the divestment by the Earl of Aylesford of the surrounding lands.

Records relating to Burham Court Farm

A near contemporary plan [below] of Burham Court Farm was found in a different set of records: an agreement for the farm, dated 11th October, 1856. However, it does appear to have been copied from the Aylesford Estates Ledger: the plot numbering; and areas; and tinting of the areas is also coherent with the Cubitt – Aylesford deeds. Importantly it is reflective of the period immediately after the initial land transactions and the establishment of the works by Cubitt in 1851-3.

The map’s orientation doesn’t make sense of the compass marked on it when compared to other mapping sources such as Ordnance Survey. In fact the map appears to be a mirror image on a casual comparison to an Ordnance Survey map of the period.

Plots 26 & 27 coloured brown on the plan are, for sure, a part of the Cubitt works. Plots 105 & 107 tinted green could possibly be the areas of land being conveyed to Lord Aylesford by Cubitt in the 19th August, 1851 deed [Kent Archives U234/E4] which contains the language, also in consideration of the said Thomas Cubitt conveying to the said Earl of Aylesford or as he shall direct…..which piece of land is delineated in the plan hereinto appended(?) being coloured green, although it has to be noted that the acreage is not correct. What this does tell, with a degree of certainty, is that Cubitt had started to acquire lands for this project prior to 1851 and from their location they would likely have been for chalk quarrying.

Why? is always an important question to ask with a man as practical as Thomas Cubitt.

The fact that the chalk quarry was remote from the brick works close to the foreshore indicates that the half mile link tunnel may have been contemplated for some considerable time. Given the limited power of steam engines, of the time, the idea of hauling heavily loaded wagons up a steep gradient out of the chalk pit and thence down to the brick/lime/cement works would not have been particularly practical. So even buying all of the intermediate lands to run a surface railway would not have assisted matters from a practical point of view.

Chalk quarry was also largely carried out by gravity in an era before steam shovels. Chalk being a soft material could be hand quarried: men would descend the slope of the chalk quarry held by ropes from the top of the escarpment and use crowbars to displace the chalk which then descended by gravity and was directed, by timber staging, into the wagons below which were brought to the chalk face on railway tracks that were extended piecemeal as the workings were enlarged.

The plots tinted yellow & salmon, on the plan below, appear to be related to the West Kent Brick, Lime & Cement Works.

At least part of the 1885 transaction is available as a clear deed plan [below]. It is something of a mystery why this land was transacted as most of it never appears to have been used by The Burham Brick, Lime & Cement Co Ltd. However, it could be that this was simply an astute move to thwart the West Kent Gault Brick & Cement Company’s ambitions and indeed it allowed The Burham Brick, Lime & Cement Co Ltd to abort the Earl of Aylesford’s attempts to grant a right of way across these lands.

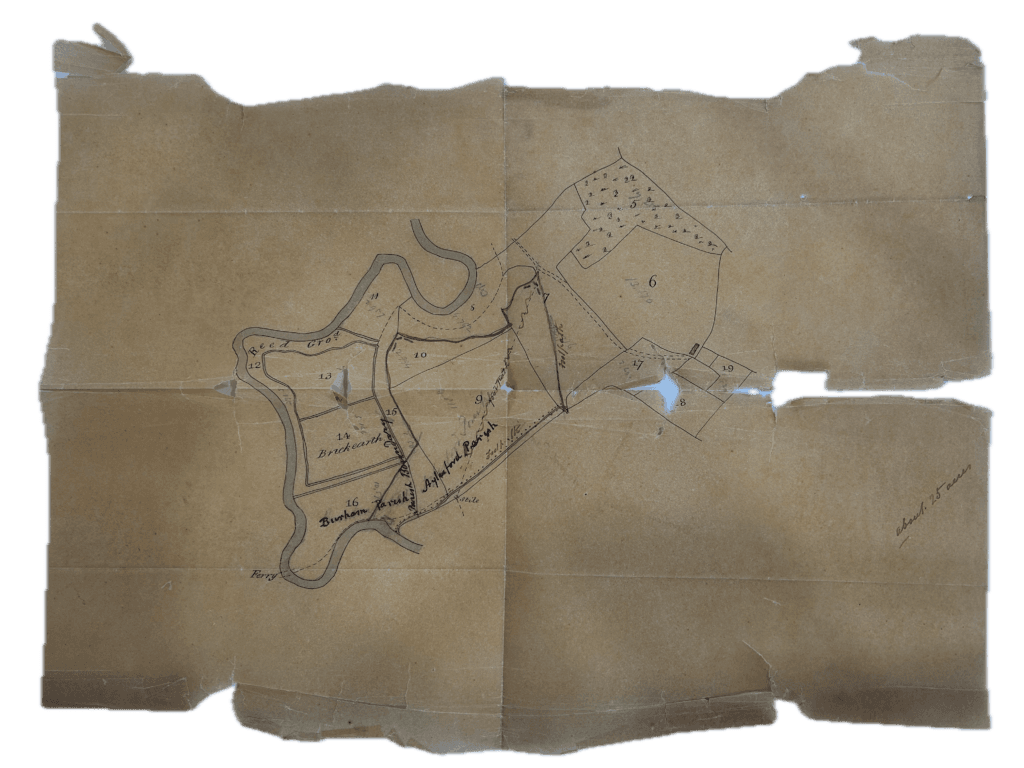

This fascinating plan [below] is included not because of its direct relevance to the Cubitt transactions but because it is an insight into the negotiation processes that lead to the them.

Frustratingly, superbly preserved auction plans exist for both the Burham Lime Works [Kent Archives U1644 E120-122 with auction catalogue description for both sites] and for the West Kent Gault Brick and Cement Company [Kent Archives SP/COLL/65/1 in near perfect condition] from the 1884 auction catalogue plans.

Petts Farm

Petts Farm [sometimes Pett’s Farm] is central to understanding the development of the chalk quarrying side of the Burham works.

The railway line [tramway on contemporary maps] for moving quarried chalk to the cement and lime works; with its cutting and tunnel running across the Petts Farm site. So the documented history of Petts Farm can give a clear insight into dating of the tunnel and therefore the vertical integration of the chalk quarrying operations.

The Sir Edmund Gregory charity founded on 24 April 1710, were the freeholders of Petts Farm until they sold it to the Burham Cement Works on 9th July, 1894. In fact Pett’s Farm was the sole asset of that particular charity. The proceeds of the letting of the farm were hypothecated to providing bread to the poor of Chatham so it was a highly significant asset that would not have been dispersed or disposed of casually.

Logically The Burham Brick Lime & Cement Works would have needed a sale or lease of lands and/or an easement for the tunnel running under Petts Farm. The surviving records are partial but they do provide very clear indications.

The half mile tunnel

The half mile tunnel is located on private lands. The lower end of the tunnel emerges into a flooded cutting. The tunnel is blocked part way down its length by chalk fill that has been deliberately inserted via a ventilation shaft.

Why is the history of the half mile tunnel so important to understanding the works?

The answer that is in several parts; Cubitt’s intent for the scale of the work; and family collaboration.

Cubitt clearly had a substantial intent for the scale of the works. He was grumbling in late 1853 that the works were not finished and ready to be viewed, which indicates that something other than simply building big sheds was going on and he would in his slightly control freakish vertical integration way have wanted to control the supply of chalk to the works. Otherwise, he could easily be held to ransom by his competitors both on supply and price. As the scale of his works was significantly larger than his neighbours and he had a monster development at Pimlico to feed with huge quantities of bricks and lime [reference required to letter books].

Railways were the internet of the 1840/50’s and a sign of modernity in any plant. As was steam power and steam traction.

The tunnel itself is unusually wide and well constructed. From photographs it appears to be a twin track tunnel. Both the exceptional length and twin track width of the tunnel are highly unusual. Added to that contemporary photographs of the tunnel construction show that it is made of four layers of bricks which is unusual when tunnelling though relatively stable materials such as chalk but may be explained by the unusual width of the tunnel and the flatness of the arch.

It may well be significant that the main engine for the works was a retired cable hauling engine “our old Blackwall Railway friend“. And that this was, at least initially, the mode of traction in the works judging by the phase that the “With the single exception of the coal which is conveyed from the wharf to the kilns and engine-house there is no up-hill traffic, and even this is considerably assisted by the down pull of the loaded waggons, which also, as they go down to the wharf, help up the empty wagons back to the kiln” both from The Illustrated News of the World, 8 October 1859 reproduced below.

Both William and Lewis Cubitt were experienced railway contractors. They had constructed the line into Euston which included plenty of cuttings and tunnels so the construction of a half mile tunnel through pretty stable chalk would not have been a major challenge to them. They had also constructed a cable hauled system out of Euston to enable the low powered engines of the time to get up the gradient to Camden.

If it was to be proved that the half mile tunnel started out as a Thomas and William Cubitt collaboration then it would be a very significant survival of the brothers’ collaboration.

The pragmatic reasoning for the tunnel was, sound in mining terms, that it enabled access from the lime/cement works to the base chalk pit without a ridiculously steep climb up from the Medway. With the steam engines of the time it would have been quite impossible to haul the heavy wagons of chalk up out of the chalk pit up a very steep gradient. Whereas with the tunnel the heavily laden wagons were assisted in their descent to the works by gravity.

The general sense is that the tunnel was planned or started but maybe not finished in Thomas’s lifetime. Thomas was attracted to very complex land deals and he had the massive experienced James Hopgood to help him with them. It could well be one of the main reasons for the massive levels of investment required in the works.

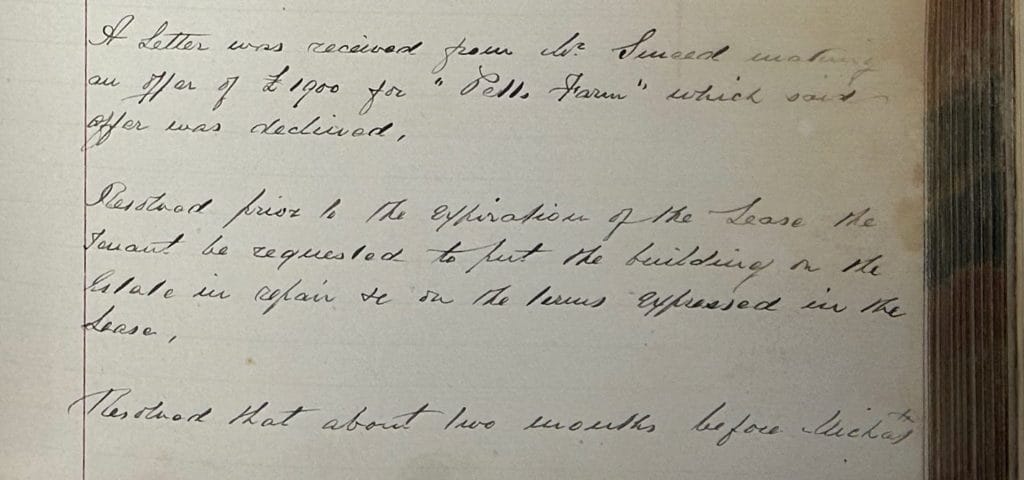

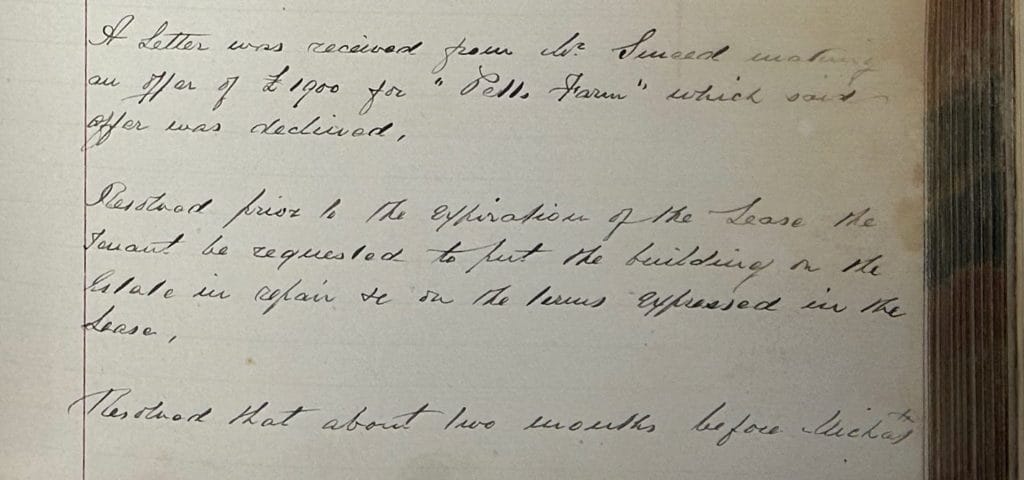

In a minute [Medway Archives, LBG/1] dated 27th April 1876 ‘A letter was received from Mr Smeed making an offer of £1900 for “Petts Farm” which said offer was declined’. There was a discussion of the offer and it was resolved to either sell the freehold or to lease it for 7 or 14 years when the tenants lease ran out.

This is interesting as it was ultimately sold to The Cement Company for £1350 [check that this is accurate] which is suggestive of either a decrease in land values or that a portion had been sold prior to the main deal or that that the easement for the cutting and tunnel had devalued that lands.

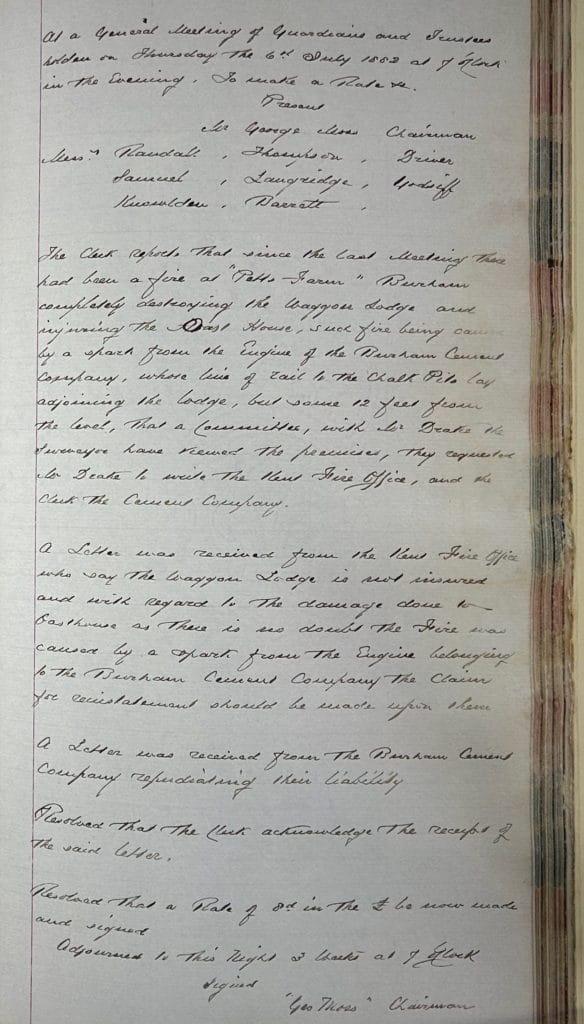

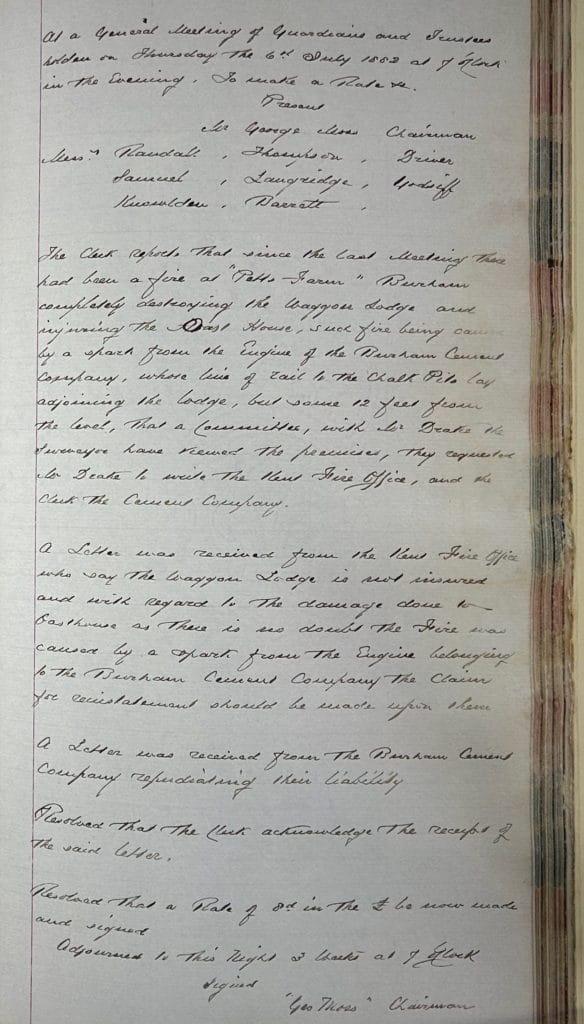

It is absolutely certain that the railway/tunnel and chalk pit were in full operation as a minute dated 6th July 1882 states that the Lodge & Oast Houses of Pett’s Farm were burned down due to a spark from .the Engine of the Burham Cement Company whose line of dial to The Chalk Pit lay adjoining the lodge but some 12 feet from the level.

This is very significant as it would imply that there was a prior agreement to either sell or grant an easement for the constitution of the tunnels and cuttings across the lands of the Charity.

The Pett’s Farm Oast houses extant today are directly beside the now flooded tunnel.

As there is no mention of any arrangements with The Cement Company, in its various guises, re Petts Farm in LBG/1, which spans 1869 to 1885, prior to Mr Smeed’s letter of 27th April 1876 it is suggested that the agreement between The Charity and The Cement Company, in its various guises, predates this. In the alternative there could, of course, be an omission in the minute book. Given the significance of the asset this seems unlikely.

In an almost illegible minutes of the 13th March 1893 Finance Committee meeting of the Board of Guardians [Medway Archives, LBG/2] a solicitor, Mr George Cossad(?) writes offering £34 per annum for Petts Farm. The minute appears to continue that the farm is to be advertised for disposal.

A further partially legible minute of 19th July 1893 appears to record various surveyors contacting the Finance Committee of the Board of Guardians re the disposal of Petts Farm [Medway Archives, LBG/2].

The purchase sum of £1,300 from The Burham Cement Company and the investment of the proceeds in Consols was agreed at a meeting of the Finance Committee of the Board of Guardians held on Thursday 7th(?) June 1893. The legibility of the entry is again poor [Medway Archives, LBG/2].

The sale of Burham Farm [note the change in naming] was recorded as completed in a minute dated 19th July 1894 [Medway Archives, LBG/3].

The changes in naming are suggestive that deeds may have been produced and filed under other names perhaps Burham Farm or Burham Street Farm deeds are relevant.

Current work

- Abstract of title to Hale farm and land in Aylesford and Burham – U234/E6 – 1868 & U1448/B6/715 – 1933 may be worthy of inspection. Hopefully with a deed plan!

- Supplemental abstract of title of Misses Hoynes to property called Dilkusha, Blue Bell Hill, Burham – Medway Archives DE1175/1/1. This could possibly be relevant.

- Mrs Smith of Culand Farm [hard to trace due to the common surname] clearly owned the lands that the newest and largest of the chalk pits was dug into. The sequence of digging is suggestive of these lands not being acquired until a later date and it is possible that they are unrelated to the construction of the tunnel.

- Farmhouse and land (159 acres) part of Burham Street farm (map annexed, and with schedule of deeds from 1846) – Kent Archives – U1863/T1 – as it is located on a continuation of Burham [High] Street.

Current avenues of research

Hobhouse cites five acres as being purchased from G. F. Furnivall in 1851; a further twelve acres in 1853 – unknown. There is no Furnivall listed in the tithe book either as a landowner or occupier.

The Glebe Lands of Burham Parish

Cubitt purchased the advowson, presumably, so he could put his own man in to control the Glebe Lands from a Colonel Milner.

Undated plan of The Burham Glebe Lands [below], possibly that referred to in the undated memorial from Incumbent Lambert Blackwell Larking to The Ecclesiastical Commissioners shows the ownership and uses of the lands prior to Cubitt’s bargains.

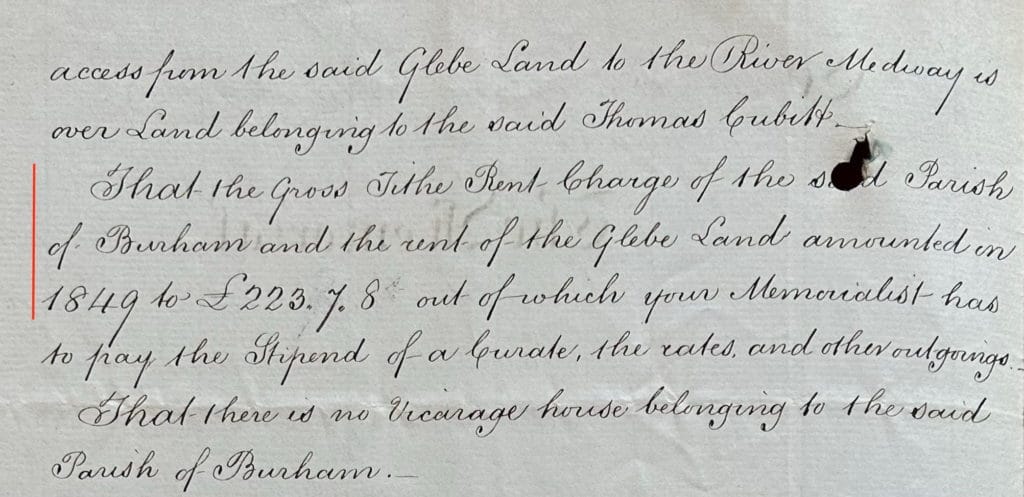

In an undated memorial [Lambeth Palace Archives – ECE/7/1/70542 – below], the Incumbent writes to The Church Commissioners setting out the proposed heads of terms as advised by John Clutton. A surface rent of £40 is proposed with a royalty charge of 1s 6d for every 67 cubic yards of brick earth manufactured into bricks tiles or other articles…..the Incumbent goes on to assert that….The Gross Tithe Rent Charge and the rent of the Glebe Lands [unfortunately the two incomes are not distinguished] amounted in 1849 to £223 7s 8d.

So, a bad bargain for the Incumbent was arrived at. Which was published in The Gazette on 24th October, 1851 21256, pg. 2775 [click link for full text as PDF of the original].

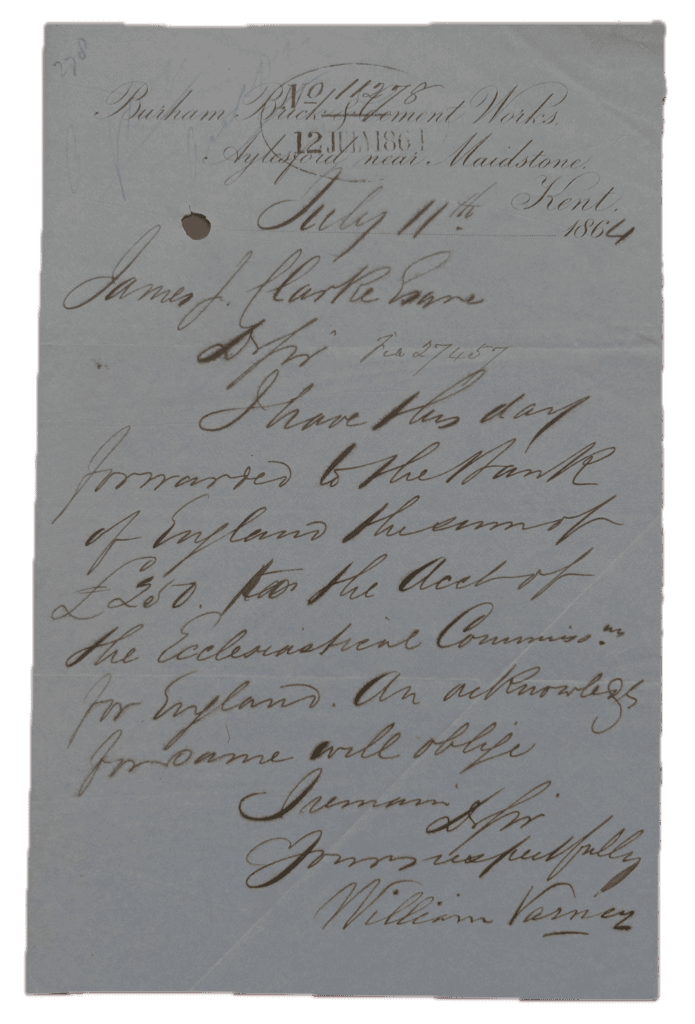

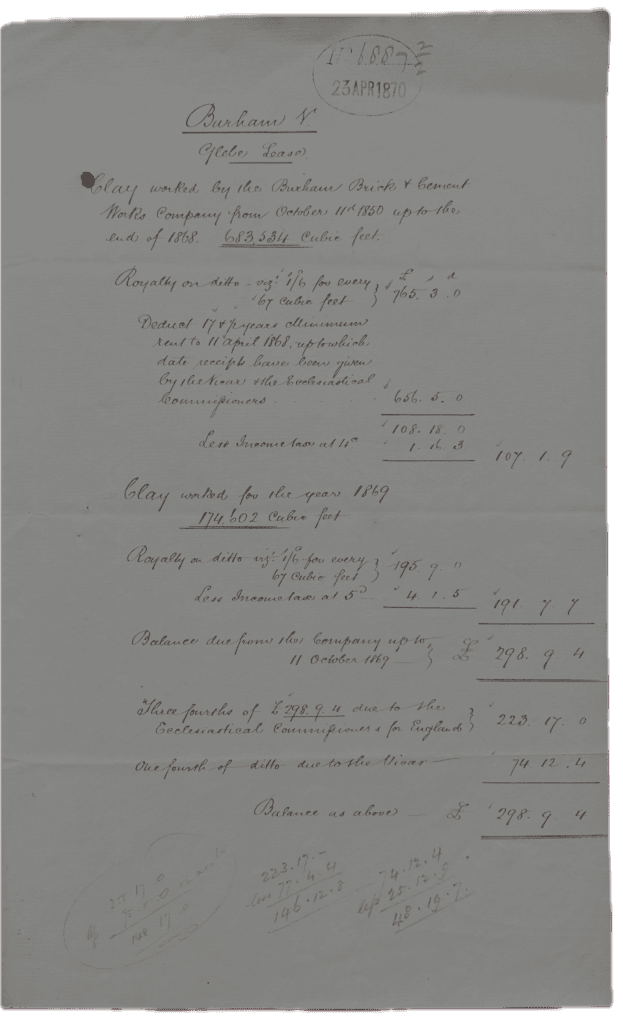

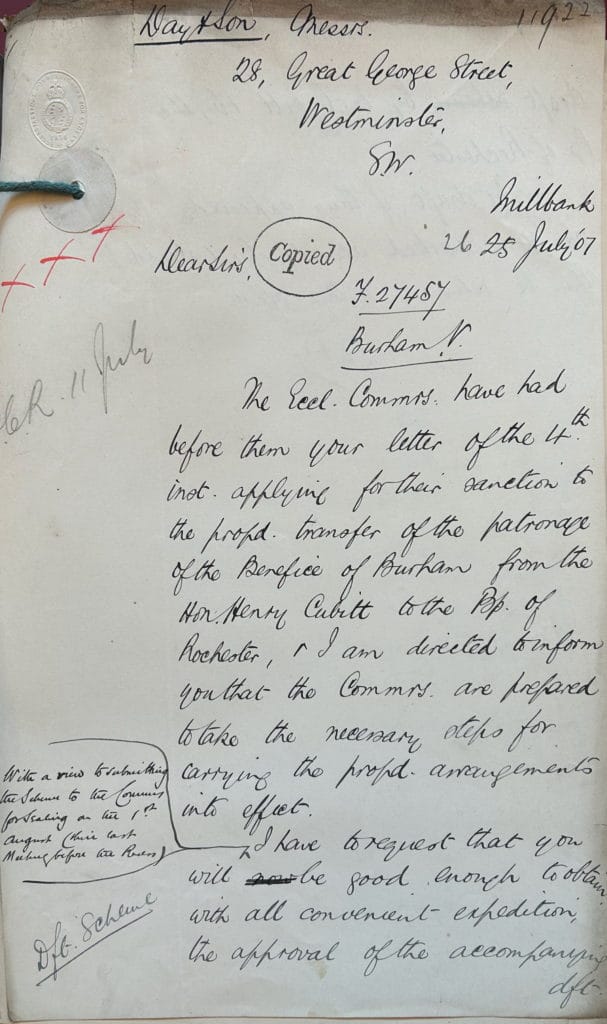

Files held at Lambeth Palace Archives [ECE/7/1/27457/1 – e.g. letter dated 12th November 1872 from William Keith, Vicar of Burham to The Ecclesiastical Commission] show that the yield from the Burham Glebe Lands was split with the majority of it, three quarters, going to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and one quarter to the incumbent.

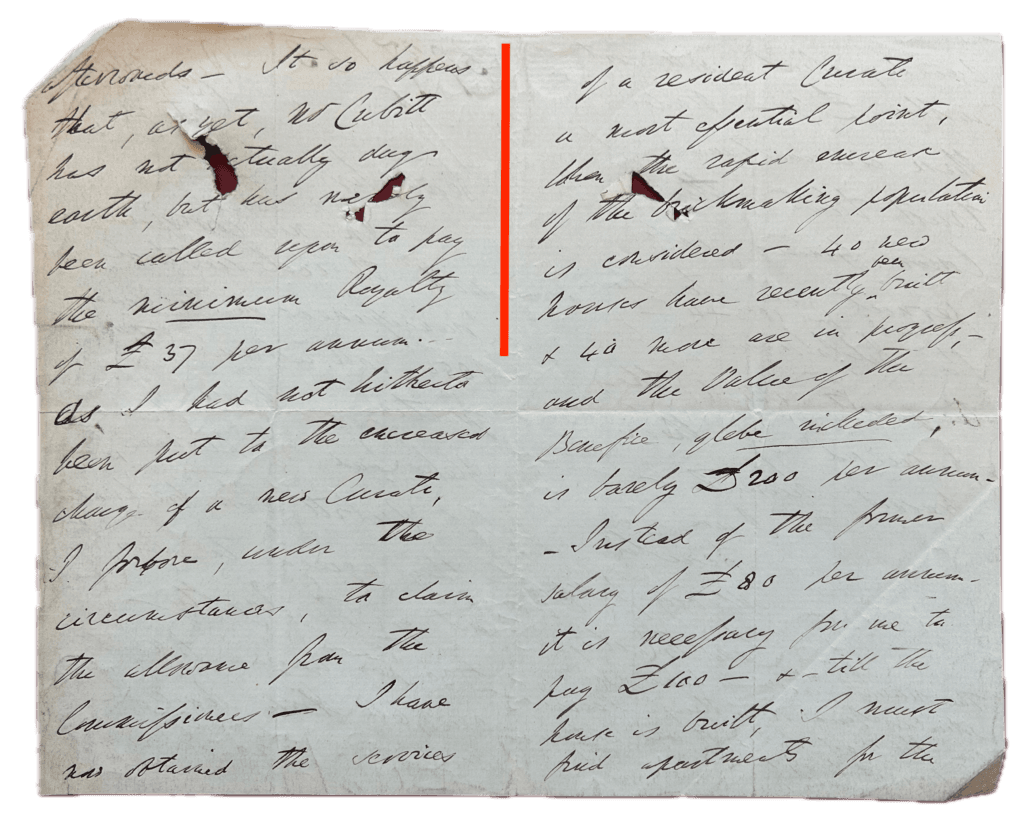

One thing that does shine though is that Thomas Cubitt quite deliberately contracted, via the lease, for a royalty based payment system based on clay/brick earth extracted from the grounds and no payment at all for the holding of the lease. A cursory examination of the tithe maps above shows that the majority of the enormous works were built on The Burham Glebe Lands and the clay pits were seemingly on land purchased from the Earl of Aylesford this was quite the ruse for some rent free lands for his massive factory! Indeed the vicar of Burham writes to The Ecclesiastical Commission complaining of this in a letter of 24th October, 1853 [below].

As if that wasn’t cynical enough, Thomas Cubitt owned the Advowson of Burham [the right to appoint the incumbent]; so William Keith was in fact Thomas Cubitt’s appointee [check and find any record of the date of the sale of the Burham Advowson in Lambeth Palace Archives].

Perhaps our Mr Cubitt was being less than entirely straight forward in the bargain he entered into for The Burham Glebe Lands?

Even so, there was constant wrangling concerning the royalty amounts due to be paid for the clay/brick earth.

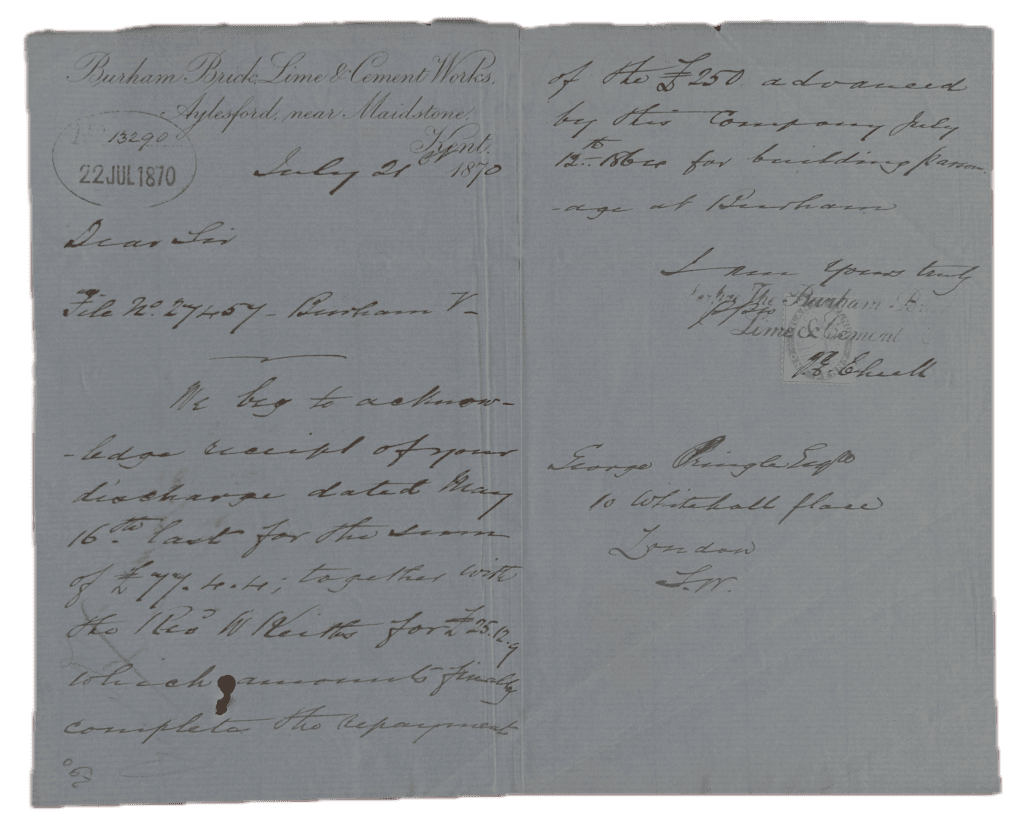

In the 1860’s the Burham Brick, Lime and Cement Company loaned £250 towards the construction of a new Parsonage in the form of an advance against the future payments for the clay/brick earth taken from The Burham Glebe Lands.

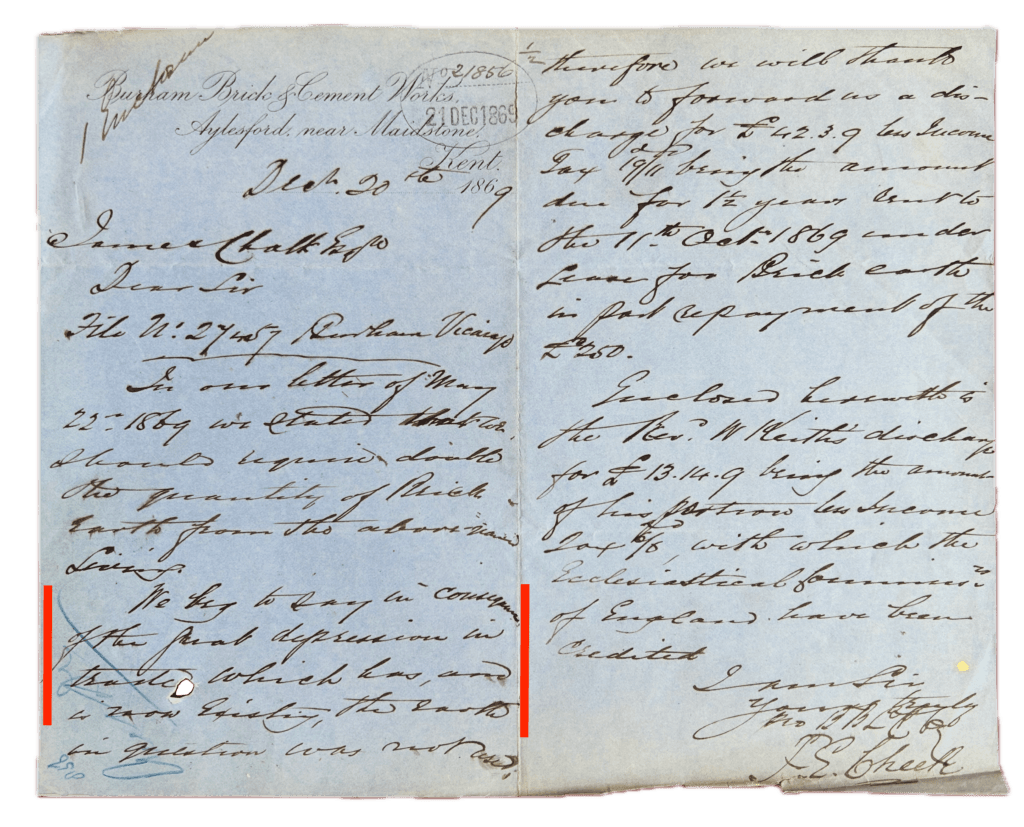

Things were clearly not going particularly well by 1869: in a letter [below] from the Burham Brick, Lime and Cement Company, dated 20th December 1869 the author is complaining ‘of the great depression in the trade’. Given that the main raw materials for lime and cement and to a lesser extent London stock gault bricks making is chalk it therefore seems entirely appropriate that the desk officer in The Ecclesiastical Commission was one James Chalk.

There is an informative account [below] which shows the level of clay abstraction 1850-68 and for 1869 from which could possibly be extrapolated the level of brick production.

By 1870 it is clear that there was a general financial tidy up going on, with the £250 advance for the new Burham Parsonage being finally settled [below].

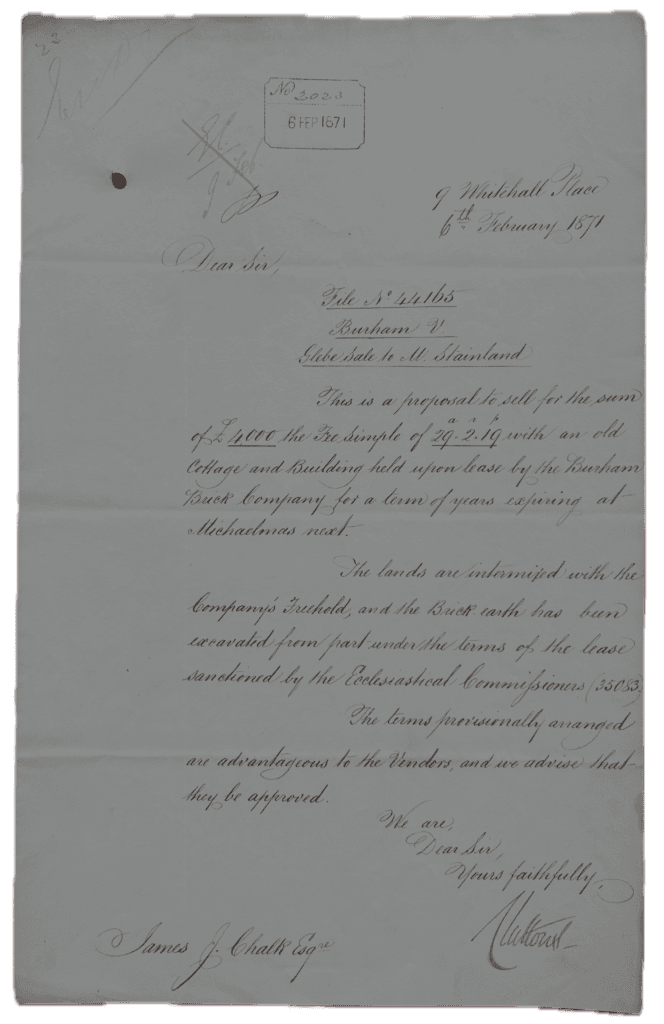

By 1871 things had clearly turned round and, possibly with new capital in hand, Burham Brick, Lime and Cement Company wanted to rationalise its land holdings and acquire the freehold of The Burham Glebe Lands. An offer of £4,000 is made for the freehold of the lands and Cluttons advise its acceptance [below] in a letter dated 6th Feb 1871.

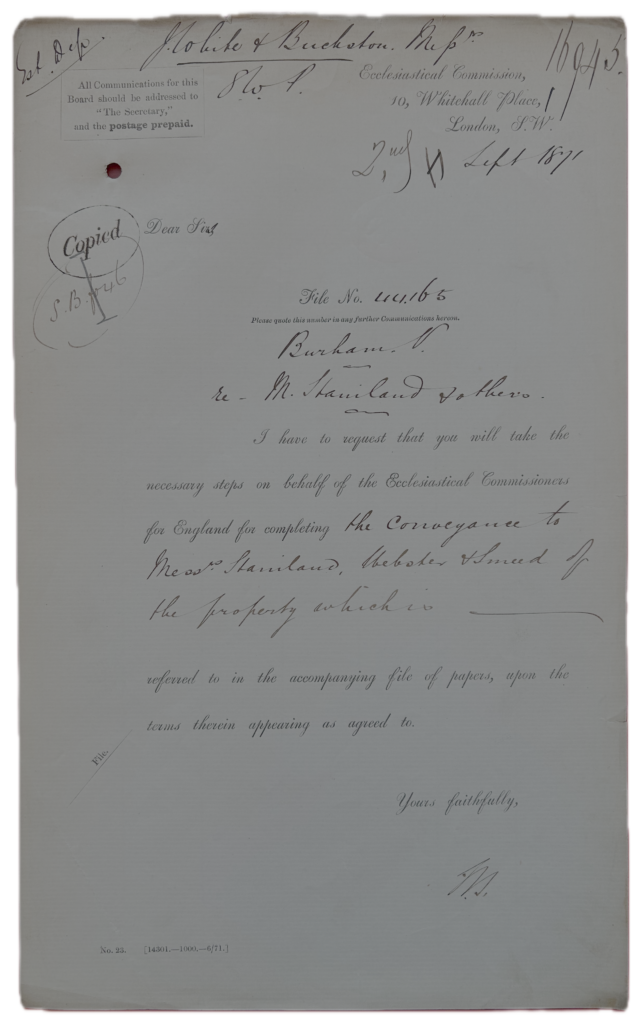

An instruction to complete the conveyance dated 2nd September, 1871 is issued by The Ecclesiastical Commission to Messrs Staniland, Webster & Smeed.

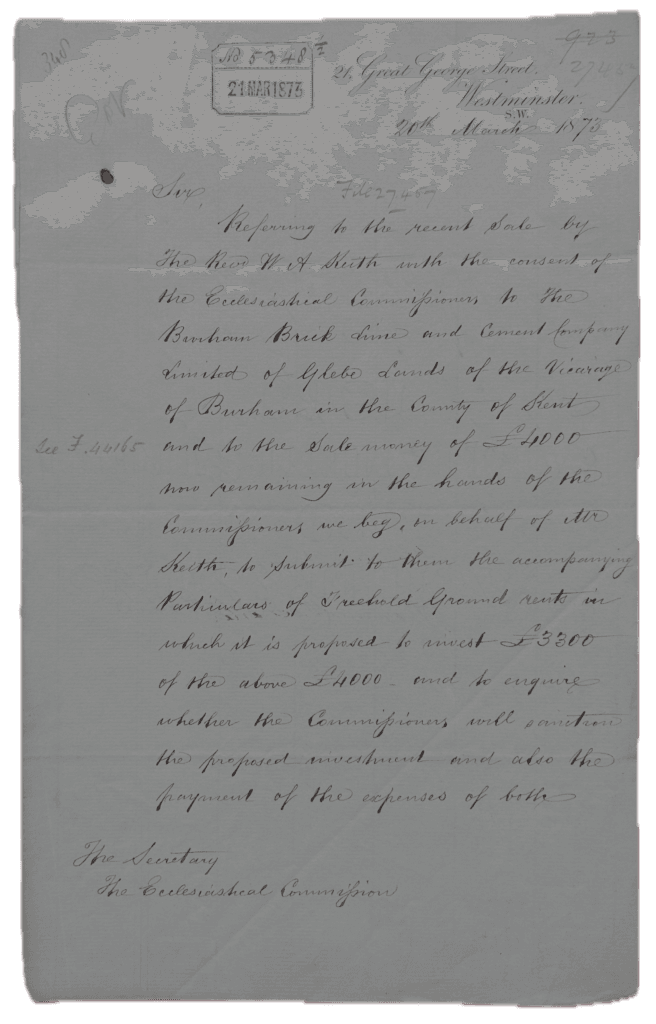

This purchase for the sum of £4,000 was assented to by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners in a file copy letter dated 20th March, 1873.

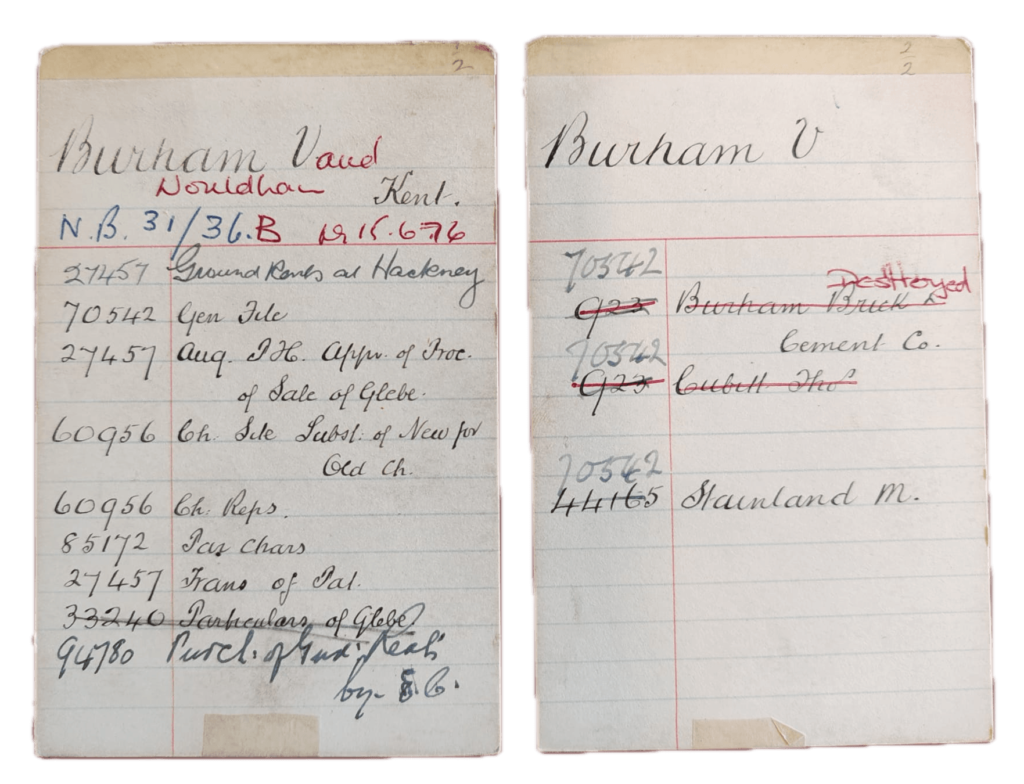

Tantalisingly there is also the index card [below] from the old Church House Archives which shows that there were separate files for the Burham Brick, Lime and Cement Company and most interestingly for Tho[ma]s Cubitt himself. Sadly these files are marked as destroyed presumably in 1976, as the hand and ink colour look similar. However, it would appear that very substantial parts of those files were transferred in 70542 which we have used in the above. We have fully imaged 70542 as it is so relevant. A partial image of 27457/1, it is a substantial file, of the most relevant elements has also been produced.

Ultimately it wasn’t until 1907 that Burham severed its relationship with the Cubitt family.

The original document that received royal assent is in the file but it has been repaired with a silk overlay and so it is very hard to reproduce a clear image of it.

The final Royal assent is recorded in The Gazette 5th November, 1907.

Ongoing work

- A close examination of the index card does show a slight glimmer of hope.

- However, the index card does appear to suggest that some of the materials from 932 Tho[ma]s Cubitt and Burham Brick & Cement Co have been transferred to 70542 General File.

- 94780 appears to be a file concerning the Parcel of Land ???? by S. G. – it is known that this is a remnant of The Glebe Lands and it is therefore suggested that it might hold materials on The Glebe Lands.

- There is also a file of Cluttons valuations of the Glebe Lands in the 1940’s ECE/SEC/BEN/GLE/4 – which might contain summary materials referring to historical agreements as Cluttons were constantly historically involved in the matter from the 1850’s.

- There are potentially confusions between Burham, Burnham and Burpham in the catalogue as some of the locational references don’t make sense and are internally contradictory.

Setting up the works

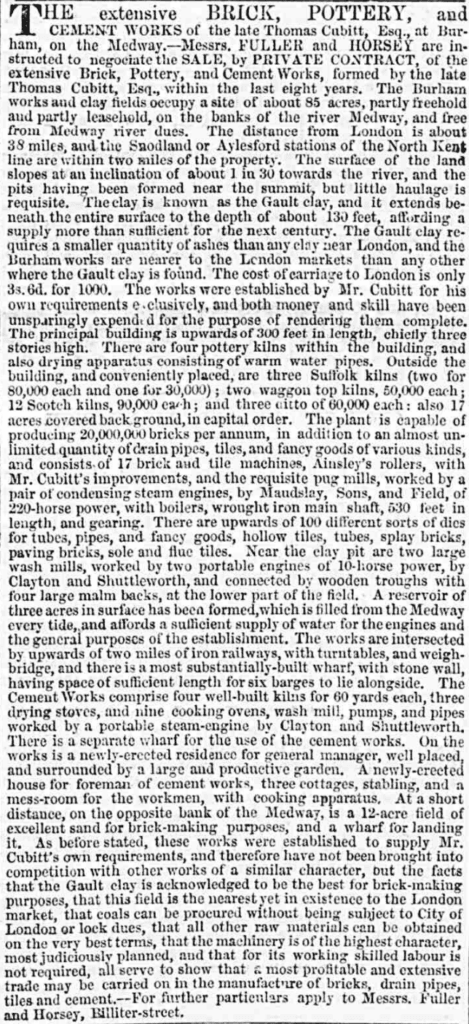

Cubitt’s Burham works are described in overly glowing terms in The Builder 19th June 1852 pg. 385 [opens the full article] as operational. The article also name checks his Thames Bank works.

[Hobhouse cites Cubit Estate Records (Fulham?? may just be included in that volume as there were pages spare). 17 acres at Aylesford includes modern sandpit; part of Lark-field land was sold to Geo. Smeed with rest of works, indicating it had brick-making potential.

When the works was put up for sale in 1857, the following plant and machinery was included: ‘2 steam engines of 110 horses each and 4 steam boilers; , double brick machines in line of Sheds, machinery in large Tilery building, Machinery in old Engine House near Clay pit, shafting, two Steam Wash Mills, pipes for……Cuthell to Chas. T. Lucas, 4 February 1857, E. 248.

An interesting schedule of equipment and provision is listed in the Morning Herald, Friday 29th October, 1858 [below].

It is worth noting that the advertorial does talk about the pits being formed near the summit. These are likely chalk pits, as there are no significant clays at the summit, as the operation of the cement works is described.

The lack of success can be ascertained from the exact same wording being printed every month in the London Morning Herald [and other papers] – thought to Friday 29th October, 1858.

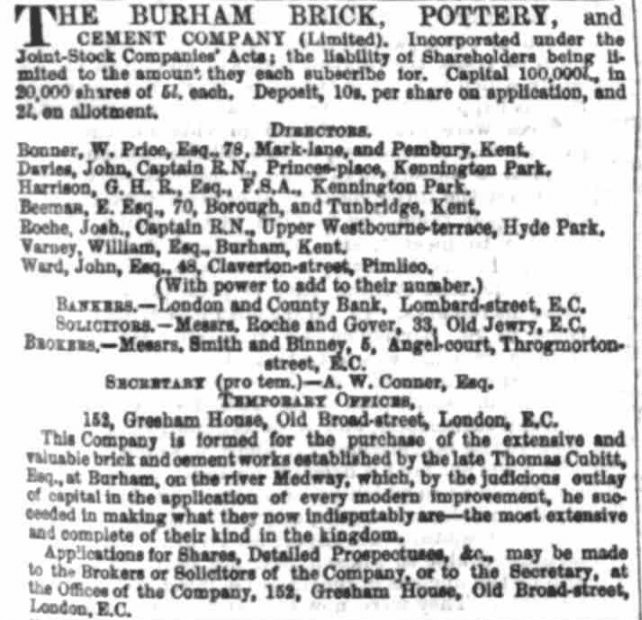

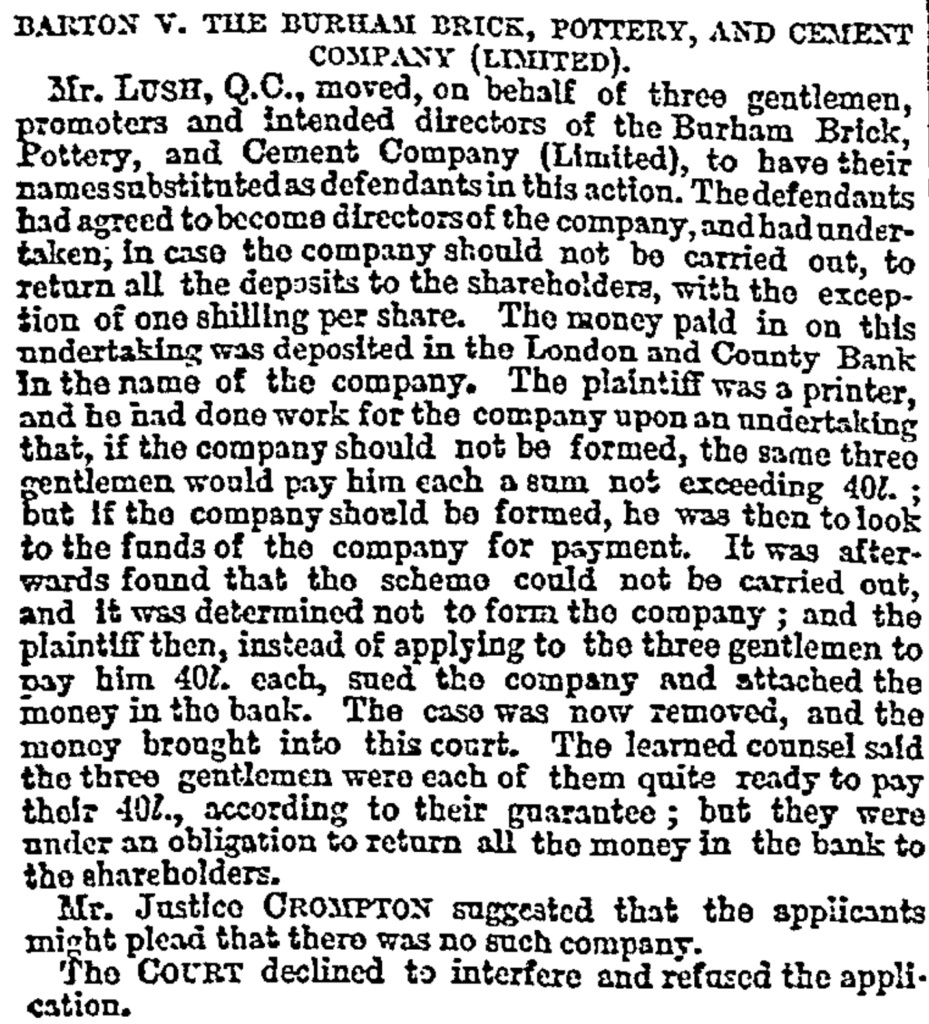

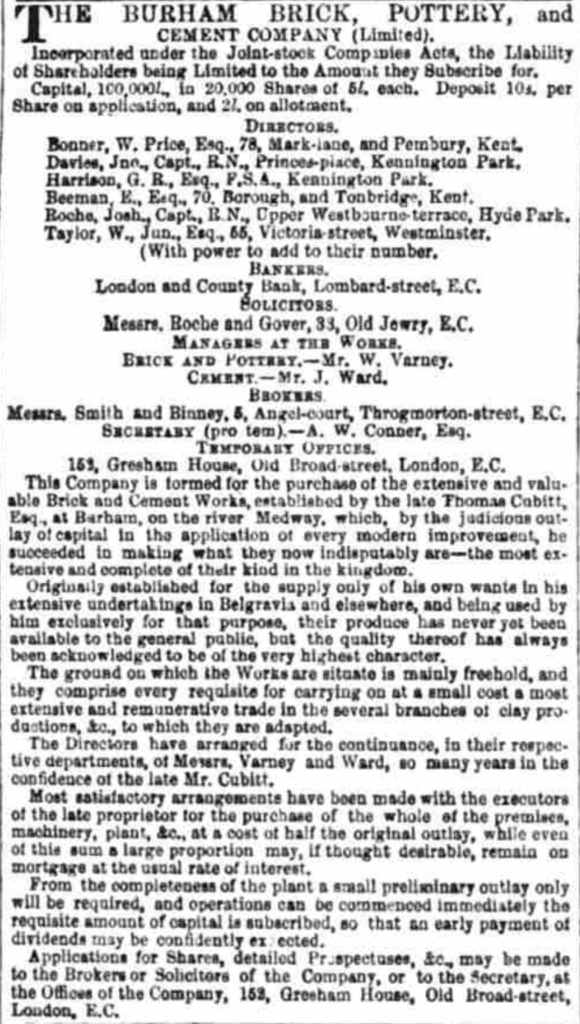

There was then an attempt to form a company, The Burham Brick, Pottery & Cement Company, with a working capital of £100,000 – this was a quite enormous sum for the time. Given how little Cubitt had paid for the lands there is more than a suggestion of disproportionately heavy investment in this huge sum of monies that Cubitt’s trustees clearly desired for the works.

This seemingly failed as tangentially demonstrated by this clipping from The Times [below].

T. Cubitt to Samuel Bailey, 4 June 1851, A. 263-4. He also trained a brick-maker for W. H. Whitbread: see letter of 19 June 1851, Cubitt Letter Book A. 272-3.]

After Thomas Cubitt died in 1855 it was operated under Cubitt Company control until 1859. As an aside, it is very notable just how much of Thomas’ empire was so rapidly dismantled after his death. In the case of the brick and cement works it is probably indicative of its relatively poor location, size and the need for continued substantial investment. There is another factor that could well have played a significant part – most of the output of the works went to Cubitt’s Grosvenor Warf by barge. As the Grosvenor and Pimlico projects progressively wound down, due to completion, the utility of having a works that was centred around barge shipping would have significantly declined. The works was also not connect to the railway which was on the other side of the Medway.

- 1854-1859 Thomas Cubitt and Co.

1859-1871 Webster and Co[this appears to be erroneous or the dates are wrong as Webster & Co appears later in the timeline according to Kent Archives U234/T4]- 1859-1900 Burham Brick, Lime and Cement Co. Ltd [we have adjusted the accepted timeline to accord with the Morning Advertiser – Saturday 06 August 1859 announcement]

- 1900-1938 APCM (Blue Circle)

An, unsuccessful, attempt seems to have been made to sell the works as early as 1857. A new partnership was formed to run it in 1859 [with Varney, Cubitt’s manager appointed as one of the six directors] this is erroneous if it is accepted that – Morning Advertiser – Saturday 06 August 1859 announcement – is correct] – it is far from clear that the works was actually sold as opposed to simply got off Thomas Cubitt & Co’s books.

The idea that the works was simply got off the books is reinforced by the following sentence in an article in The Atlas, Saturday, August 20, 1859, which states;

Since that gentleman’s death, and the completion of his Pimlico operations, the works have been offered by his executors for sale, but so gigantic are they, that no one firm have been able to grapple with them, and a company is now formed, under the name of the Burham Brick, Pottery, and Cement Company, to purchase work the property under the Limited Liability Joint Stock Act.

The key words being to purchase work the property which implies that that Cubitt’s executors would be paid a proportion of the profits rather than an outright purchase price.

Development by Thomas Cubitt

[this is the subject of active work to track down the various deeds, letters and other agreements]

July 1851 purchased 17 acres of lands at Aylsford.

December 1851 21 year lease on Glebe lands of Burham Vicarage

March 1852 purchased 100 ares farm in Larkfield

November 1852 purchase of 72 acres bordering the Medway.

[Source, Hobhouse who cites Cubitt Estate Record, Fulham Vol, which is now in a private collection. So working from accessible sources:-

Add in images of the key letter from the letter books.

Cubitt -> Bailey Cubitt Letter Book A 263-4 4th June 1851

Cubitt -> Whitbread Cubitt Letter BookA 272-3 19th June 1851

Cubitt -> Whitworth Cubitt Letter Book C 168 & 296 24th Jan 1853

Cuthell -> Lucas Cubitt Letter Book E 248 4th Feb 1857]

Letters -> Varney [presumably the James Varney who was the manager of the brickworks?] in the penultimate Cubitt Letter Book D Pgs. 267, 328, 345, 362, 404 – curious that Hobhouse didn’t cite these?]

The half mile tunnel

Why is the history of the half mile tunnel so important to understanding the works?

The answer that is in several parts; Cubitt’s intent for the scale of the work; and family collaboration.

Cubitt clearly had a substantial intent for the scale of the works. He was grumbling in late 1853 that the works were not finished and ready to be viewed, which indicates that something other than simply building big sheds was going on and he would in his slightly control freakish way have wanted to control the supply of chalk to the works as he could easily be held to ransom by his competitors both on supply and price. Also the scale of his works was significantly larger than his neighbours and he had a very large development at Pimlico to feed with huge quantities of bricks and lime [reference required to letter books].

Railways were the internet of the 1840/50’s and a sign of modernity in any plant. As was steam power and steam traction.

It might well be significant that the main engine for the works was a retired cable hauling engine “our old Blackwall Railway friend“. And that this was, at least initially, the mode of traction in the works judging by the phase that the “With the single exception of the coal which is conveyed from the wharf to the kilns and engine-house there is no up-hill traffic, and even this is considerably assisted by the down pull of the loaded waggons, which also, as they go down to the wharf, help up the empty wagons back to the kiln” both from The Illustrated News of the World, 8 October 1859 reproduced below.

Both William and Lewis Cubitt were experienced railway contractors. They had constructed the line into Euston which included plenty of cuttings and tunnels so the construction of a half mile tunnel through pretty stable chalk would not have been a major challenge to them. They had also constructed a cable hauled system out of Euston to enable the low powered engines of the time to get up the gradient to Camden.

If it was to be proved that the half mile tunnel was a Thomas and William Cubitt collaboration then it would be a very significant survival of the two brothers collaboration.

The pragmatic reasoning for the tunnel was sound in that it enabled near level access from the lime/cement works to the base chalk pit. With the steam engines of the time it was quite impossible to haul the heavy wagons of chalk up out of the chalk pit up a very steep gradient.

The general sense is that the tunnel was planned or started but maybe not finished in Thomas’s lifetime. It could well be one of the main reasons for the massive levels of investment required in the works.

In a minute [Medway Archives, LBG/1] dated 27th April 1876 A letter was received from Mr Smeed making an offer of £1900 for “Petts Farm” which said offer was declined.

It was resolved to either sell the freehold or to lease it for 7 or 14 years.

This is interesting as it was ultimately sold to The Cement Company for £1350 [check that this is accurate] which is suggestive of either a decrease in land values or that a portion had been sold prior to the main deal or that that the easement for the cutting and tunnel had devalued that lands.

It is absolutely certain that the railway/tunnel and chalk pit were in full operation as a minute dated 6th July 1882 states that the Lodge & Oast Houses of Pett’s Farm were burned down due to a spark from .the Engine of the Burham Cement Company whose line of dial to The Chalk Pit lay adjoining the lodge but some 12 feet from the level.

This is very significant as it would imply that there was a prior agreement to either sell or grant an easement for the constitution of the tunnels and cuttings across the lands of the Charity.

The Pett’s Farm Oast houses extant today are directly beside the now flooded tunnel.

As there is no mention of any arrangements with The Cement Company, in its various guises, re Petts Farm in LBG/1, which spans 1869 to 1885, prior to Mr Smeed’s letter of 27th April 1876 it is suggested that the agreement between The Charity and The Cement Company, in its various guises, predates this. In the alternative there could, of course, be an omission in hte minute book. Given the significance of the asset this seems unlikely.

In an almost illegible minutes of the 13th March 1893 Finance Committee meeting of the Board of Guardians [Medway Archives, LBG/2] a solicitor, Mr George Cossad(?) writes offering £34 per annum for Petts Farm. The minute appears to continue that the farm is to be advertised for disposal.

A further partially legible minute of 19th July 1893 appears to record various surveys contacting the Finance Committee meeting of the Board of Guardians [Medway Archives, LBG/2].

The sale of Burham Farm [note the change in naming] was recorded on a minute dated 19th July 1894 – no sum is stated. Previous minutes pages, in the volume, refer to Petts Farm.

The 1859 sale

The plant was initially primarily concerned with brick making, using the gault clay extracted immediately adjacent to the plant, but also made hydraulic lime and Portland cement. The initial installation was described on its sale in 1859 as “consisting of engine and house, washing mills, some four kilns, with accompanying drying stoves and nine coking ovens”.

The announcement of the formation of The Burnham Brick Pottery & Cement Company [Morning Advertiser – Saturday 06 August 1859] gives a fairly detailed account of whom held what roles including their bankers London & County.²

The wording of the Morning Advertiser article of Saturday 06 August 1859 is quite suggestive of simply getting shot of the Burham site as fast as possible as Thomas Cubitt’s trustees had no interest in it whatsoever now that all the major Cubitt developments, such as Pimlico, were drawing to a close and the scale of the business was reducing.

Most satisfactory arrangements have been made with the executors of the late proprietor for the purchase of……at a cost of half of the original outlay…..while even of this sum a large proportion…..remain on mortgage at the usual rate of interest.

This is also suggestive of over investment into the site.

Given the article in the The Atlas, Saturday, August 20, 1859 uses the phrase to purchase work the site then it is reasonable, as a starting assumption, to presume that the mortgage was provided by Cubitt’s trustees.

There is a very full account of the works in, The Illustrated News of the World, on 8 October 1859. This needs to be taken with a judicious pinch of salt as was almost certainly instigated by the new owners.

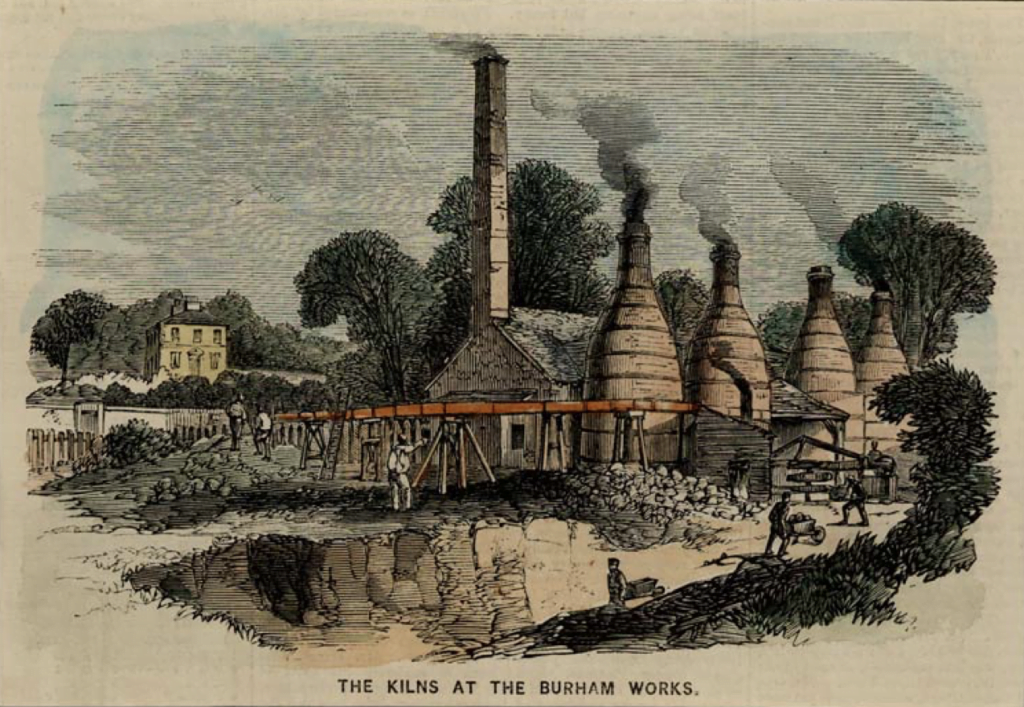

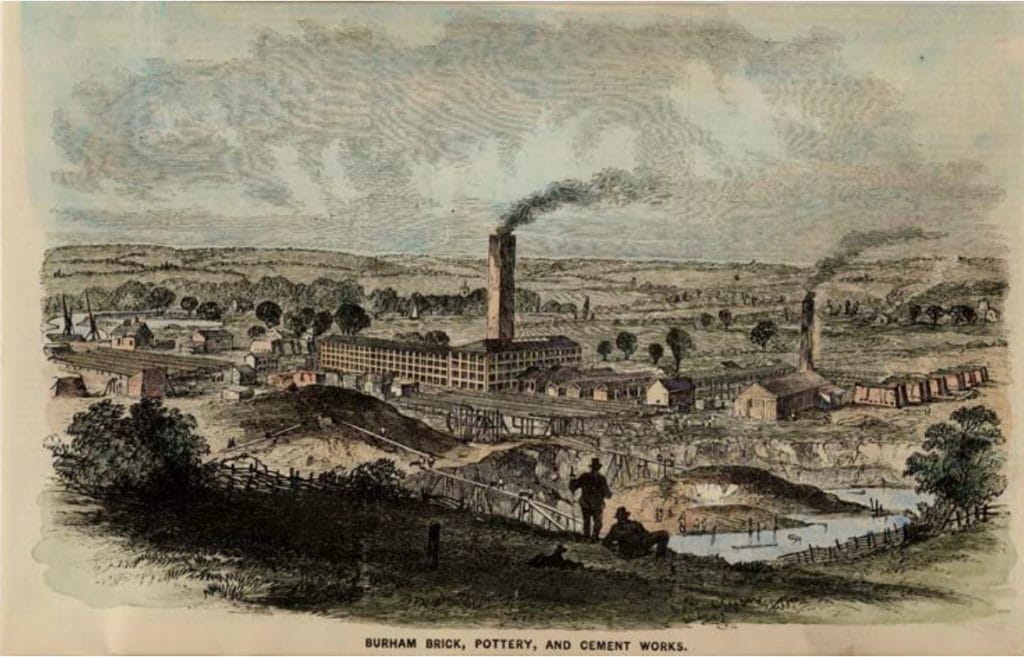

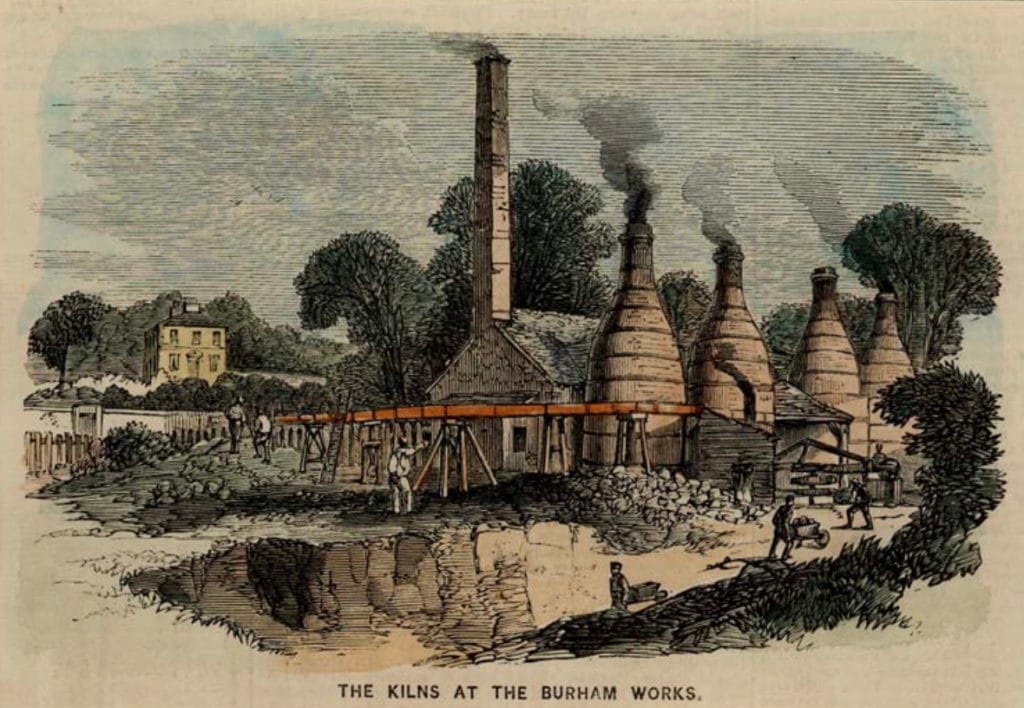

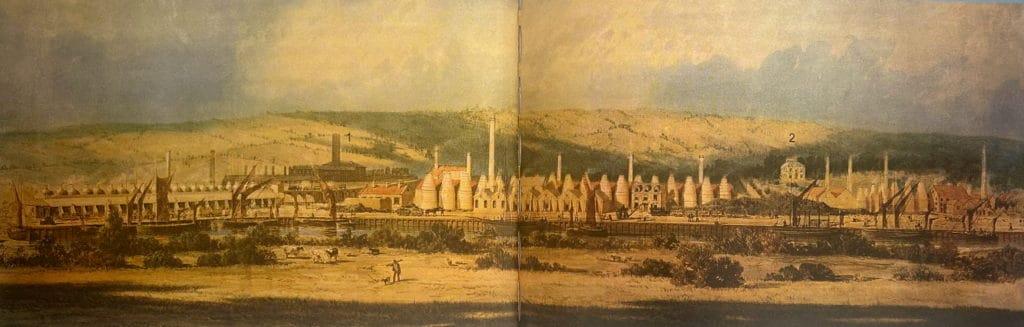

“We present our readers, on this page, with two engravings illustrative of these extensive works. It is well-known throughout the building trade that the late Mr. Thomas Cubitt’s works at Burham produced the very best bricks and pottery ware that could be profitably brought into the London market; and that the whole establishment, under the superintendence of the present manager, has arrived at a degree of perfection which will render it very difficult for any other brick-field in London to compete with that at Burham in respect of prices. In order to give our readers an idea of the extensive nature of these works, we cannot do better than lay before them the following account furnished by a gentleman who has visited this establishment. He left London one morning, by the 10.15 North Kent train, and arrived at Snodland in two hours. “On the journey we passed,” he says, “many brick-fields of various extent, and after passing Strood they became more frequent, but in none of them did we see more than is ordinarily to he seen in such places. After passing Cuxton, the Wouldham and other cement works were pointed out to us on the banks of the Medway, and immediately after, long before our arrival at Snodland, we saw the large pottery and engine house of Burham, with its immense square shaft rising up in the valley, and reminding us very forcibly of the large building on the banks of the Thames at Pimlico, so well known as Cubitt’s workshops, and now in the occupation of the Government.

On alighting at Snodland, we crossed the Medway in a ferry boat, and after a walk through the fields of about mile past the old church of Burham, we arrived at the works. The first objects of interest that attracted our notice were numberless rows of little sheds, under which the bricks are dried and which are termed hack grounds. These little sheds, about six feet high by three and half broad, cover upwards of seventeen acres of ground, and are situated between the brick machines and the kilns, and are intersected with lines of tramways. The whole estate is on a slope, falling gradually about one in eighty-five towards the wharf on the river, which fact considerably facilitates the economical working, as all the heavy material goes down hill, and in no case does any material or article have to travel over the same ground twice. At the top of the hill the clay is now dug, and is crushed and washed on the spot. The manager of the works, Mr. W. Varney, who was upwards of forty years in Mr. Cubitt’s employ, informed us that he had in the first instance selected the estate for Mr. Cubitt, and that the whole of the vast works had been erected and developed under his own immediate and residential superintendence. The clay is about 130 feet thick, and will last for a century to come. After being washed and crushed, the clay is conveyed in waggons or tramroads to the pugging.

mills and machines, where, after going through a very simple process of squeezing, squashing, and pressing, it issues forth from the various machines, through the dies, in the shape of bricks, either solid or hollow, and tiles of all sorts, sizes, end shapes. These are generated, so to speak, by the machines with a wonderful rapidity, and conveyed by boys off the machines on to harrows, in which men wheel them into the drying hacks, under which they are stored to dry, previous to being stacked in the kilns for burning. All the brick machines are worked by one long shaft, 520 feet long, which receives its motion from the large engine of 220-horse power. This engine we found to be an old friend, being the one formerly worked at the Minories Station to wind up the endless rope on the Blackwall Railway, when the trains on that line were propelled by the well-known wire-rope. This engine, which is by Maudslay and Field, does nearly all the work of the place—pumping water, crushing clay, flint stones, &c., working the pug-mills, and all the brick, tile, and drain-pipe machines.

The latter articles are all made in the large building forming part of the engine- house. There are four floors, 400 feet long, on all of which drain-pipes, ornamental flower and chimney pots, tiles, &c., are made and dried, the beat from the boilers and the pottery kilns being turned off from waste into various pipes and chambers for heating the rooms, and so drying those goods which are not suitable for out- door drying in the hacks, previous to burning in the kilns. The number of moulds and wooden frames to receive the several articles when first formed, and when the clay is still plastic and liable to damage by handling, is really surprising. To give some idea, there was one pattern for hollow tiles of which Mr. Varney informed us there were in stock 80,000. The more elaborate articles made in this building are burnt in the kilns in the building; but the stronger and coarser goods are burnt in the out-door kilos with the bricks, and from each floor is a tram-road down an incline for waggons, leading direct from the pottery house, with the goods when dry, to the kiln where they are burnt, and the manufacture is so arranged that the heavy goods are made on the lower, and the lighter on the upper floors, so that in loading (as it is termed) a kiln of dry goods for burning, the heavy and stronger articles are at hand for the lower portion, and the more fragile goods for the upper tiers. After being burnt, the goods then ready for market and use are drawn out of the kiln on the opposite side to where they are loaded, and are placed on trucks on the line of rails immediately contiguous to the kiln doors, and are thence conveyed down the gentle incline of about 1 in 85, either to the wharf, to be at once loaded into barges and sent away, or to be stacked on the stock ground to await purchasers. With the single exception of the coal which is conveyed from the wharf to the kilns and engine-house there is no up-hill traffic, and even this is considerably assisted by the down pull of the loaded waggons, which also, as they go down to the wharf, help up the empty waggons back to the kiln. Thus much horse labour is done away with, and, instead of a large stud, only a very few are requisite to do the work. Some idea of the completeness of these carrying arrangements may he arrived at by the knowledge that there are upwards of three miles of tram and railroad on the works, with numberless turn-tables, weighbridges, etc. Nothing here is wasted; all the broken bricks, drain pipes, and even what few stones there are in the clay, are ground up to powder in a powerful mill worked by the large engine; and on being mixed up with the clay, form a material out of which some superior quality of goods are manufactured. “A never-failing supply of water is obtained front the river, which feeds a reservoir of some three acres in extent; and at the wharf, which is of the most substantial description, and stone-faced, some six barges may be loaded at once. At high tide there are fourteen feet of water at the wharf. Adjoining the wharfs are the cement works, consisting of engine and house, washing mills, some four kilns, with accompanying drying stoves and nine coking ovens.

Nothing strikes a visitor to these works more than the substantial character of everything on the estate. All is of the most solid construction, perfectly unlike any other brick works we ever visited. In most cases a few boards roofed in with tiles, forming a tumble down looking shed, forms all the building one sees, except the huge square masses of burning bricks, called clamps. At Burham everything is made as if to last for ever—all is Cubittian in its appearance, and everything is burned in kilns of the most approved construction. In addition to the large engine—our old Blackwall Railway friend—there are three others of various power; and all the necessary workshops, with room for the men, foremen’s cottages, &c., are in their places.

Near the top of the hill is a most substantial house, indeed quite a mansion, which overlooks the works. This is the residence of the out-door manager, Mr. Varney; and on viewing the whole field, with its various and numerous engines, buildings, tramways, kilns, wharves, &c., one cannot but see that here are what may be justly termed the model brick-works. Here are concentrated the results of near half a century’s experience and improvements. Everything is in the right place. Nothing superfluous. Every possible attention has been given to economize labour and material, and every advantage taken of the natural position of the estate. When in full work, between 600 and 700 men and boys are employed, and from 25,000,000 to 30,000,000 of bricks, besides tiles and pipes, can readily be turned out from the works; which, however, can be considerably augmented without any great outlay, or increasing the present steam power.”

Andrew Ashbee, comments in, Snoldand and Cementopolis 1841-1881 pg. 50

“The cement kilns at Burham shown above were sited beside the river and separately from the main brickworks. The view [of the plate above] also shows William Varney’s house ‘Varnes’ [to the left rear of frame]. The account tells us that he ‘he had in the first instance selected the estate for Mr. Cubitt, and that the whole of the vast works had been erected and developed under his own immediate and residential superintendence.’ If Varney had been ‘upwards of more than forty years in Mr. Cubitt’s employ’ that suggests he had begun some time prior to 1820; he appears in the 1841 and 1851 censuses living in Pimlico, presumably in premises provided for him by Cubitt. His first wife Maria died in 1842 and a year later he married Lydia Williams. By 1851 he had become a ‘brickmaker superintendent’ so was well placed for his forthcoming responsibilities. Thomas Cubitt died in 1855 and the family put the Burham works up for sale in 1857. A new partnership was formed to run it in 1859 with Varney appointed as one of the six directors [Ed. this may be erroneous].¹ In his latter years he had a house in Lower Fant, Maidstone, where he died on 30 August 1894, leaving an estate valued at £16,211. 15s. 6d.”

The chalk mining operation – to make the cement and the lime has left considerable physical traces including a number of tunnels, one half a mile long, as well as the massive chalk pits themselves.

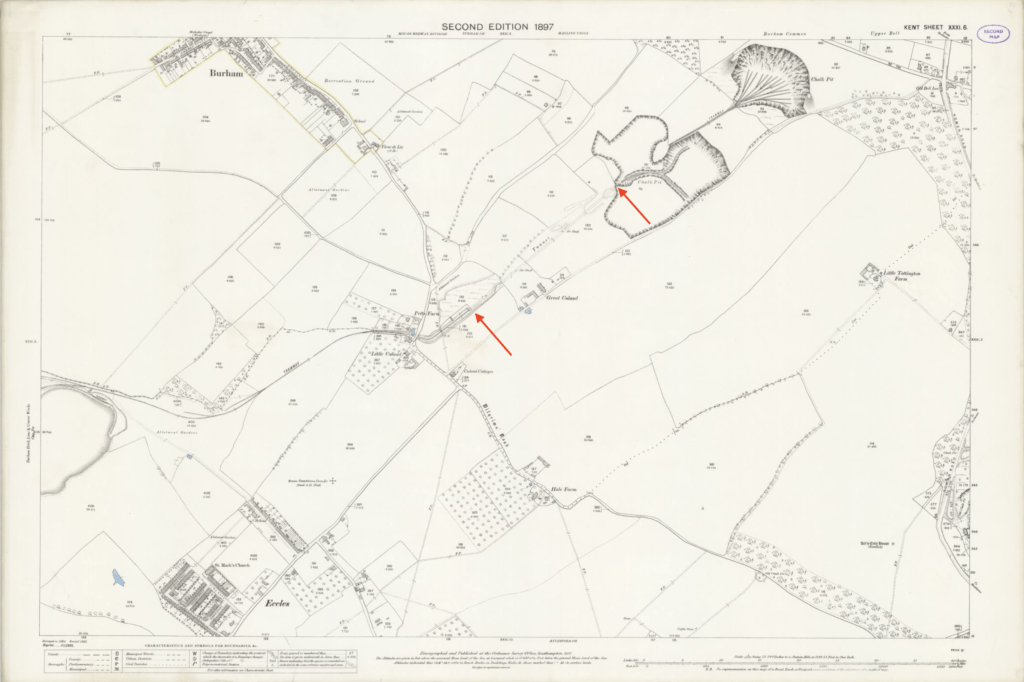

It is uncertain when the half mile tunnel was built that linked the two chalk pits together. It is clearly present in the 1897 large scale OS map below. The tunnel portals are identified with red arrows. It is very possible that this was constructed, or at least started, in the Cubitt era as the tiny excavations shown in the 1860’s OS maps would have been rapidly exhausted by production of this scale and Cubitt clearly operated the works at great scale as there was a claimed output of 25,000,000 to 30,000,000 bricks per annum [presumed] in The Illustrated News of the World, 8 October 1859 article.

This is further implied in the The Illustrated News of the World article which states that there was “…that there are upwards of three miles of tram and railroad on the works….” It is relatively hard to see how three miles of track is laid out if the nearly one mile of line in the half mile tunnel is not included in that.

A 20th century tramway tunnel running from Margetts Chalk Pit towards Great Culland Chalk Pit. The tunnel is 2.7m wide and 2.8m high with a concave roof. The lower part of the side walls is of concrete shuttering, above this the walls are of yellow brick. The central part of the tunnel has collapsed, evidently because its walls were of timber [this is inaccurate]. It is possible that this occurred during construction as bricks were stacked near the collapse [there is no evidence for this in many other sources]. As such, it is possible that the tunnel was never completed and therefore never reached Great Culland Chalk Pit [this is not correct as there is ample evidence that it was worked].

……..The length of tunnel accessed by KURG [Kent Underground Research Group] before the collapse coincides with a large depression behind the Rectory. This feature first appears on the 4th edition mapping of the area.

In the 1907 surveyed 1910 published version of OS sheet OS Kent sheet XXXI NW the far chalk pit closest to Blue Bell Hill is marked “Chalk Pit” implying active use.

In the 1933 surveyed 1936 published version of OS sheet OS Kent sheet XXXI NW the far chalk pit closest to Blue Bell Hill is marked “Old Chalk Pit” implying disuse. It was know to be worked out to the boundaries of the lands that the company owned. The chalk pit opposite Great Culland had been excavated in this time using the railway tunnel to transport the chalk back to the works via a minor tunnel under the road. Thus the half mile tunnel transported huge volumes of chalk over its decades of use.

Clearly the tunnel would have been constructed for a sound business reason as it would have been a major investment and presumably to access a better type of chalk stratum more suitable for the work of the plant.

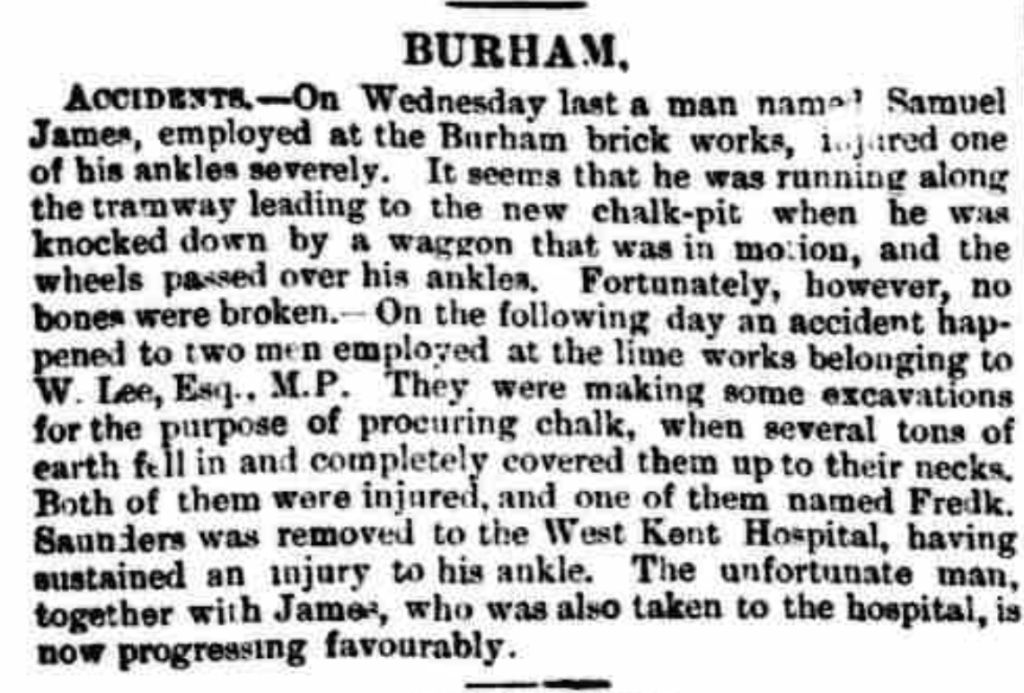

An 1868 press clipping [Maidstone & Kentish Journal, 24th August 1869 pg. 8] mentions the tramway to the new chalk pit following an accident on the tram line. So it seems likely that the tunnel was in use before this date. It would not have been quick to dig such a tunnel which suggests that the planning of the chalk quarry and the tunnelling works had started some time before. Maybe it was this putative plan that scared off Cubitt’s executors and made them offload the site at such a significant discount to the sums expended?

A view of the works [below] in 1885 in it’s full pomp with its brickworks fully intact.

The works in the 1940’s before the site was cleared

Date flown: 12 January 1946

Sortie: RAF/106G/UK/1112

Photographer: RAF

Pilot: RAF

<script async src=”https://static.smartframe.io/embed.js”></script><smartframe-embed customer-id=”27025fea9afa38753501b02dbd8a40f2″ image-id=”raf_106g_uk_1112_rp_3036″ style=”width: 100%; display: inline-flex; aspect-ratio: 4463/5314; max-width: 4463px;”></smartframe-embed><!– https://smartframe.io/embedding-support –>

After the cement works closed

Part of the site was used for rocket assembly and testing during WWII – the link opens the wartime remenisences of some of those who worked there.

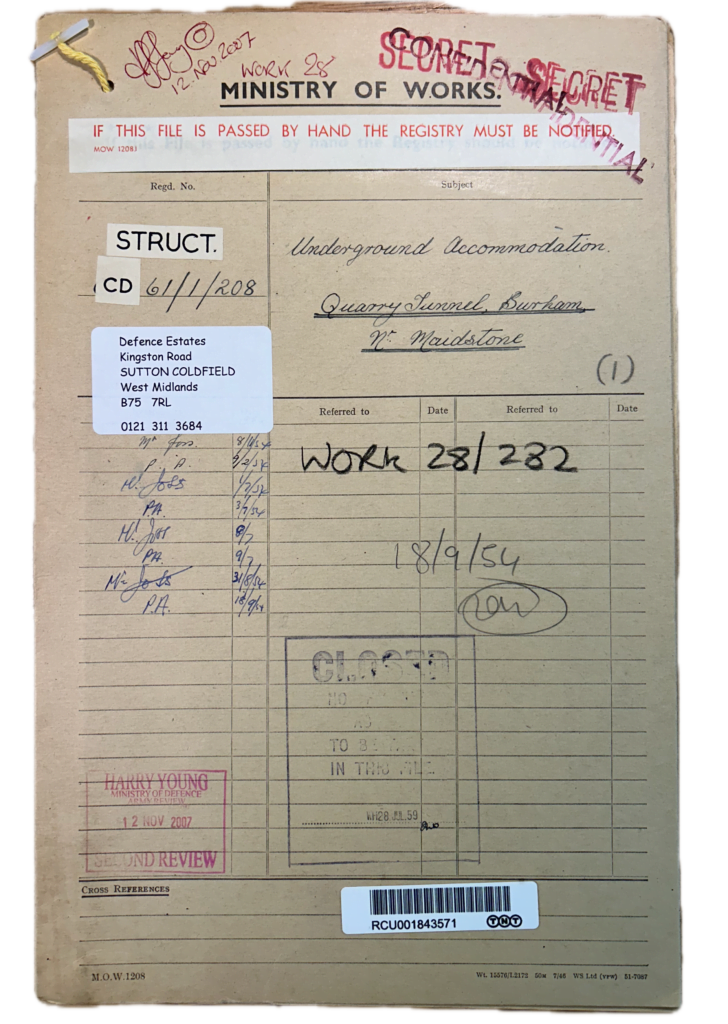

It is clear that the main ‘half mile’ rail tunnel was surveyed by The Ministry of Works during the 1950’s for use a nuclear fallout shelter [The National Archives – Underground Accommodation: Quarry Tunnel, Burham, near Maidstone, Kent (1) – TNA – WORK 28/282]. That can be deduced from how the record is filed in the series Underground Accommodation.

Although the contents of the file have an air of low comedy: with the surveyor sent out to inspect the tunnels unable to find them due to an incorrect map reference and then when finally the map reference is corrected he cannot access the main tunnel because of trees and other vegetation!

In a final loop back to Cubitt, the Kemp Town railway tunnel is also mentioned in the same file as Item f CD/61/1/208 [below].

Brick making in general

Kathleen Watt wrote an entire PhD, in 1990, entitled “Nineteenth Century brick making Innovation in Britain: Building and technology Change” the following passages are relevant to Cubitt’s brick and tile making enterprises:-

Pg 87 –

“Cubitt’s experiments undoubtedly reassured many building professionals of the superior strength and quality of bricks pressed by machinery.”

This is interference to the idea that machine made bricks were inherently inferior to hand made bricks. Cubitt extensively crush tested his bricks.

Pg 135 –

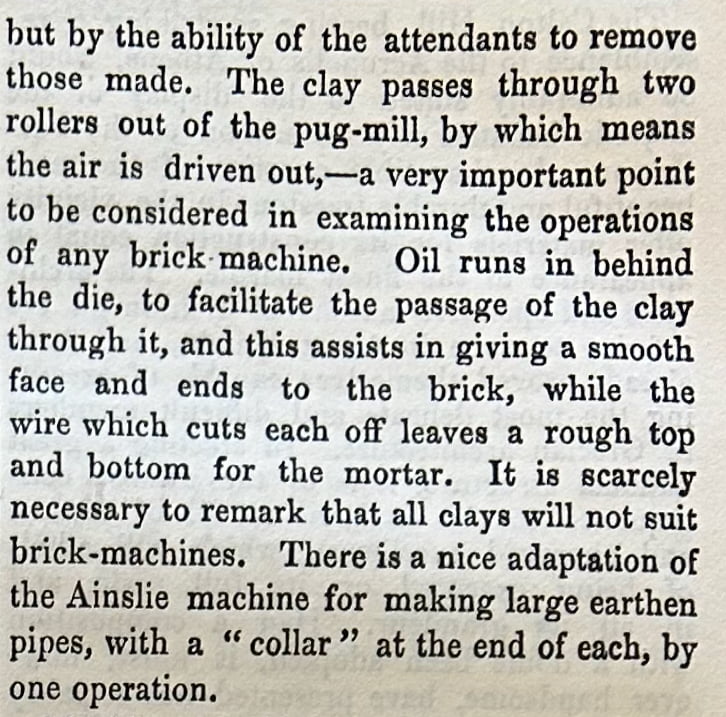

“Evidently, despite his association with this company, by mid-century Ainslie entered into other agreements to manufacture his subsequent patents. In 1850 at the RASE meeting at Exeter, it seems he had formed another enterprise with William B. Moffatt, a manure manufacturer from London. Listing his address as Perryhill, Sydenham, Kent, Ainslie and Moffatt exhibited samples of manure and Ainslie’s newest tilemaking machines, “having a new mode of feeding, by the addition of one roller in connection with the other two”, 1. e. his patent of 1846 (RASE 1850, p.155). This raises a question of which machine patented by Ainslie did Dobson refer to as being popularly used for brickmaking prior to mid-century. In discussing the Ainslie machines improved by Thomas Cubitt and used at his large works at Burham on the Medway, Hermione Hobhouse illustrated the new roller machine patented in 1846, but cited an 1852 description of Cubitt’s works in The Builder. This article clearly mentioned the clay moving through a die: “The clay passes through two rollers out of the pug mill, by which means the air is driven out…011 runs in behind the die, to facilitate the passage of the clay through it” (The Builder 1852, p.285; Hobhouse 1971, p.313). This suggests that Ainslie’s earlier patented machines rather than his roller extrusion machine were more commonly known and adopted.”

Pg 178 –

“The Burham Brick, Pottery and Cement Company Limited was formed in 1859 to purchase works that had been established by Thomas Cubitt in 1853 at Burham on the Medway. The company purchased all the buildings and machinery used by Cubitt including seventeen Ainslie brickmaking machines (“improved by Cubitt”), pug mills, washmills and steam engines totalling 220 horse-power to operate the works (The Builder 1859, [the issue is not specified and it is not the October issue] p.655; Hobhouse 1971, p.311- 13)”

1800 and early 1900’s photos of the site:-

Lime kilns – image – MMPR-AYLSFD-114 – https://kentphotoarchive.org.uk/searchlarge/?townkeywordname=BURHAM&featurekeywordname&startnumber=1&pagenumber=2

Lime kilns – image – MMPR-AYLSFD-113 – https://kentphotoarchive.org.uk/searchlarge/?townkeywordname=BURHAM&featurekeywordname&startnumber=0&pagenumber=2

Overview photo – SMPC-BUR013 – https://kentphotoarchive.org.uk/searchlarge/?townkeywordname=BURHAM&featurekeywordname&startnumber=19&pagenumber=2

View from church tower into chalk workings – SMPC-BUR014 – https://kentphotoarchive.org.uk/searchlarge/?townkeywordname=BURHAM&featurekeywordname&startnumber=20&pagenumber=2

Later Surveys

Some of the area was turned into a water works and there is a considerable volume of papers surviving from that at Manchester University;

GB 133 EMP/3/109 – River Medway Scheme: Proposed Bewl Bridge and Ticehurst Storage Reservoirs including Valley Crumple boreholes and Chingley Fault Zone; Medway Water Order (Bewl Bridge Reservoir), Parliamentary Bill, and Public Inquiry; proposed Burham Treatment Works; Eccles Lake and Treatment Works.

Photographs and negatives (Bewl Bridge Reservoir), maps, plans, correspondence including Mid-Kent Water Co., test data, piezometer records, borehole logs, contract documents, reports including site investigation, calculations, press cutting, Morton and other reports, diagrams, etc.

Image/painting

Listed as Lafarge Cement UK on pg 112/3 og Andrew Hann’s The Medway Valley as a watercolour (?) from 1885 of the post Cubitt works showing the Cubitt building.

Notes on the site geology [called Culand Chalk Pits click link for PDF download of the site which is now defunct] – https://culandpits.org/ contains interesting information on the geology of the area by Nick Baker.

The relevant title deeds appear to be these and the deeds might contain further information on the

The price stated to have been paid on 26 July 2001

for the land in this title and titles

K427542 – states original filed continued under K839946 – no older information & no mention of tunnels,

K764031 – states original filed continued under K829085 – no older information & no mention of tunnels,

K829085, only goes back to 6 May 1903 – no older information & no mention of tunnels,

K830702 – Original filed under K829085 – no older information & no mention of tunnels,

K830706 – no older information & no mention of tunnels,

K830709 – no older information & no mention of tunnels – TITLE CLOSED – REGISTRATION CONTINUED UNDER K859495

K830710 – “Licence to erect a wharf wall dated 5 April 1854 made between (1) Rochester City Council and (2) William Peters affects the land between points A and B and between points C and D on the filed plan. ¬NOTE: Copy filed.”

“Licence to maintain a wharf dated 13 May 1884 made between (1) The Conservators of the River Medway and (2) The Right Honourable Earl Poulett and Frederick Robert Knollys affects the land between points E and F on the filed plan. ¬NOTE: Copy filed.”

TITLE CLOSED – REGISTRATION CONTINUED UNDER K859495

K859495

Licence to erect a wharf wall dated 5 April 1854 made between (1) Rochester City Council and (2) William Peters affects the land between points A and B and between points C and D on the title plan. ¬NOTE: Copy filed under K830710.

Licence to maintain a wharf dated 13 May 1884 made between (1) The Conservators of the River Medway and (2) The Right Honourable Earl Poulett and Frederick Robert Knollys affects the land between points E and F on the title plan. ¬NOTE: Copy filed under K830710.

Licence to extend a wharf dated 13 August 1907 made between (1) The Conservators of the River Medway and (2) Henry Peters affects the land between points B and C on the title plan. ¬NOTE: Copy filed under K830710.

K839946 – no older information & no mention of tunnels,

K830710 – no older information & no mention of tunnels,

was £8,521,996.

K829085 – appears to contain the information required

PROPRIETOR: TRENPORT INVESTMENTS LIMITED

(Co. Regn. No. 01265480) of 20 St James’s Street,

London SW1A 1ES.

RESTRICTION: Except under an order of the

registrar no transfer of any part of the land in this

title which includes either of the tunnels marked T1

and T2 on the plan to the Transfer dated 26 July

2001 made between (1) Blue Circle Industries Plc

and (2) Trenport Investments Limited is to be

registerred unless a solicitor certifies that a Deed

of Covenant has been entered into in accordance

with Schedule 5 of the said Transfer.

NOTE 3: The Tunnels and structures between

Original filed under K488215

Pethers Patent Tiles and Bricks

The Burham, Brick, Lime & Cement Co Ltd was well know for producing the intricate Pethers patent tiles and bricks. These were much used by architects such as William Butterfield.

Pether, Henry

Henry Pether was the second youngest son of Abraham and Elizabeth Pether. Born in Chelsea on 15 March 1800, he moved with the family to Southampton in c.1805. He was christened – seven weeks after his father’s death – at All Saints Church on 31 May 1812. He became an artist, specialising like his father and elder brother Sebastian in moonlight scenes. He exhibited a view of Calshot Castle by moonlight at low water at the Royal Academy in 1828. He collaborated with his brother-in-law Thomas Henry Skelton in a series of lithographs of the town in 1830. He lived at 29 Beach View before moving to Greenwich in the early/mid 1830s. His sister Eliza continued to live in Southampton with another of his sisters – Helen, wife of T H Skelton – until the 1860s.

Henry Pether had a remarkably varied life. In 1836 he was surveyor and engineer to the abortive London and Portsmouth Railway which offered a direct line between the capital and Portsmouth docks. Sydney Smirke was named in the first prospectus as his colleague. In January 1837 Pether was a prisoner in the London and Middlesex debtors prison in the City of London, facing trial in the Court for Relief of Insolvent Debtors. In April 1839 he was granted a patent, with Alfred Singer of the Vauxhall Pottery, for a machine which cut tiles out of thin layers of clay. These were used to create ornamental mosaic pavements, characterized by Grecian, Arabesque and Gothic patterns. Although produced for only a limited time at the Vauxhall Pottery, the tiles graced several important buildings, including Charles Barry’s masterpiece the Reform Club (notably the much admired tessalated pavement in the entrance hall), the Royal Exchange and Blenheim House. A second patent, dated May 1867, was for a new method of producing ornamental bricks. Manufactured by the Burham Company of Aylesford, Kent out of local deposits of Gault clay, Pether’s diaper bricks were pale buff moulded bricks capable of taking very sharp detail. They could be made to almost any design and were a cheap and durable means of decoration, particularly for spandrels and stringcourses. They were much favoured by William Butterfield, architect of the Gothic revivalist (eg St Augustine’s Church, Kensington). Thomas Alfred Skelton – son of TH and Helen Skelton – used his uncle’s bricks as decoration in his rebuilding of 153 High Street, Southampton for the pharmaceutical chemist Edwin Whitlock in 1871. And throughout this turbulent life Henry Pether continued as a landscape painter. The BBC Your Paintings website has 40 oil paintings by (or attributed to) Henry Pether. These include ‘Southampton Town Quay at sunset’ and ‘Town Quay by moonlight’, both in Southampton City Museums. His ‘Venice by moonlight’ is in Southampton Art Gallery.

Henry Pether died, at Stockwell Green, Lambeth on 20 February 1880, a few days shy of his 80th birthday.

Source http://sotonopedia.wikidot.com/page-browse:pether-family

This is suggestive that Thomas Cubitt only used the Pethers process for making tiles as at the Vauxhall Pottery. The Pethers Bricks Patent was not seemingly obtained until 1867 [British Patent No. 1867/1569, dated 28 May 1867] making it highly unlikely that Thomas Cubitt would have used this process in his lifetime as he died in December 1855.

There is also a well referenced article on Pethers Patent Bricks by Alan Cox in the British Brick Society Journal [click to open link – article on page 17].

¹ This conflicts with the information in, Morning Advertiser – Saturday 6th August 1859 – which has Mr Varney as the brick and pottery manager and not as a director.

² Personal communication 1st July 2024, Nat West Archives “We hold very few customer records from this time for this bank. I’ve had a look at the records and we don’t hold anything relevant for the period around 1859.”

³ The conventional way to make shaped bricks a standard brick used to be taken and this was then cut as close as possible. The resulting shaped brick was finished by rubbing it with a harder abrasive material. This had a number of disadvantages in that it wasted volumes of material, it took a lot of manpower, it was slow and tedious but worst of all with imperfect brick firing the cores of the bricks were often quite soft so when the hard outers were rubbed away a softer core was exposed that was less resistant to weathering. Part of what Cubitt set out to do was to make constant quality bricks by drying them before firing them thus reducing the firing energy and time required to bake them to the core as well as the discolouration to the outside of the bricks by the elongated firing process. The way the brick kilns were designed also meant that the firing temperature was more even across the whole kiln. Cubitt also wanted to mould that shaped bricks.