The Heaver Estate Balham

The Heaver Estate Balham

A regency style mansion, called Bedford Hill House, was sited roughly where nos. 12-18 Veronica Road now stand. Access was from Bedford Hill along a lane that lay just south of the current line of Ritherdon Road.

On the far side of the Falcon Brook was a farm facing the Common. By the 1880’s this was known as Elms Farm, from which Alfred Heaver took the name of his Elms Estate scheme and also Elmbourne Road.

Some development took place in the 1820’s, by Richardson Borradaile, which included ‘Hamilton House’, and ‘Swan House’ on Balham High Road service from this early development.

Bedford Hill House and the estate of some forty acres of park and pasture land, was then owned by William Cubitt, brother of the very well known developer/builder, Thomas Cubitt. Soon after acquiring the estate, Cubitt enlarged the house and landscaped the grounds, using the Falcon Brook to feed a large fish pond with an island in the middle occupying what are now the rear gardens of houses at the south end of Manville and Huron Roads.

The opening of Balham Station on the 1st December 1856 brought pressure to release land for speculative house building, gathering momentum as the demand for housing increased.

In January 1865 the Metropolitan Board of Works approved expenditure of £30,000 to cover over, deepen and redirect the length of Falcon Brook from Balham to the River Thames. The Falcon Brook had, by then turned into more of a drainage channel and the pleasant brook that had watered the Bedford Hill House orchards and filled the fish ponds was now a distant memory.

For a time, Bedford Hill House lay empty, a remnant of early Balham, with the houses of the Heaver Estate gradually encroaching upon its lawns and gardens. By 1897, with the building of Veronica Road, it too, was finally demolished.

The Ordnance Survey 1868-1881 Surrey County Maps still shows essentially empty fields other than development along Balham High Road.

By the time of the Ordnance Survey 1896 London Series Maps development is well underway with both Huron and Streathbourne Roads half built out from Balham High Road, Elmbourne Road Completed and Drakefield and Louisville Roads starting their build out from Balham Hight road as well.

Tithe Maps and Tithe Books

The Tithe Map and Tithe apportionments make the extent of Alfred Heaver’s development operations very clear. Incidentally he also developed a patch of land either side of Wandsworth Bridge Road.

Alfred Heaver – the man who created The Heaver Estate

Alfred Heaver (10 February 1841 – 8 August 1901) was an English carpenter turned builder and property developer, responsible for the construction of a number of housing estates amounting to thousands of homes in south London, including the Heaver Estate in Balham. He was murdered in 1901 by a relative who nursed a grudge against him.

This is where things get a bit murky and some effort needs to be made to separate facts, from primary sources, from good sounding stories that have been recirculated over the decades.

The Survey of London dubs him “the big-scale yet shadowy South London developer-builder”. [Chapter 10: The Shops of Clapham Junction”. Survey of London 49: Battersea (draft) (PDF). English Heritage / Yale University Press. 2013].

Whilst it is true that Heaver did go bankrupt after an early building venture [“The Bankruptcy Act 1869” (PDF). The London Gazette. 14 March 1871. p. 1407] this trope is demonstrably far from the truth: the 1907 Tithe records, above, show the majority of the properties has been promptly remortgaged to The Prudential Assurance Company. This is a very sensible and logic manner of proceeding with secured cashflow. This is also about the most impeccable source of funding that you could wish to have.

From an initial examination of the building and deeds records it would appear that Heaver kept one in twelve of the houses for himself and sold or remortgaged the others. This makes a great deal of sense as a well run small to medium enterprise would expect a net profit of 5-8%.

Heaver clearly learned from his earlier troubles and set himself up on a very clear and straightforward path.

Keith Bailey states, without any apparent investigation, that the source of capital for his entrée into large-scale estate development is unclear [Bailey, Keith Alan (1995). The Metamorphosis of Battersea 1800-1914: A Building History (PDF)(PhD). The Open University].

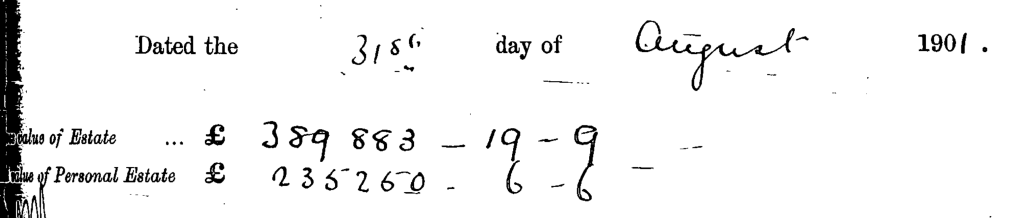

Keith Bailey goes on to state, without any evidence other than a press clipping with a differing amount, that the size of Alfred Heaver’s estate, after his murder, was uncertain [Bailey, Keith Alan (1995). The Metamorphosis of Battersea 1800-1914: A Building History (PDF)(PhD). The Open University].. However the probate register entry for Alfred Heaver is quite clear and it was not revised at all. So this looks perfectly above board. The fact that probate was granted in the same month as his death also points to his affairs being in good order. Examination of the Grant of Probate, dated 31th August 1901, reveals the source for this misinterpretation of plainly stated facts: The Wandsworth Brough News had simply added the value the Personal Estate [£235,260] to the value of the Total Estate [£389,883] to produce a sum of £625,143. This shows the very clear value in going back to primary sources – such errors are plain to see.

The level of the organisation of Alfred Heaver’s estate can be gauged from a number of sources. The two most substantial being his massive and detailed will [click for full PDF] and The Deed of Arrangement [click link for full PDF] which was made prior to his death split the huge amount of housing stock which he owned between his sons.

A close reading of Alfred Heaver’s 25 page will of 1898 also gives the impression of a very businesslike, clear and organised mind. The one thing that does leap out from the page of the will is that his early partner Coates isn’t treated as being close to him but merely as an employee [pg. 4]. Given that his children are provided with sevenths of the estate, this two sons get two sevenths each of the nearly £400,000 or each seventh being worth £57,000 in 1901 money.

Upon further trust if my present manager Edward Coates shall at my death be in my

employ as manager then to pay to him a weekly salary of eight pounds and eight shillings

if and so long as my said trustees shall continue to employ him as manager of my trust

estate and it and when he shall become incapable through illness accident or any other

cause to act as such manager to pay to him a pension of four pounds and four· shillings.

per week during the remainder of his life……

Edward Coates shall though capable refuse to or to continue as manager aforesaid

or if my said Trustees in the exercise of their discretion (which shall be absolute

regard to this matter) either, shall decline to employ him, or shall dismiss him from his

employment as such manager (either on the grounds of his employment being unnecessary or

on any other ground) then my said Trustees shall pay to him a sum:of five hundred pounds

free of duty and thereupon the said weekly payment of eight pounds and eight shillings shall

cease and the pro vision for payment of the said pension shall become inoperative but

none of the said weekly-payments-made prior to such refusal or dismissal of the aforesaid

shall be taken or considered to be in part satisfaction or discharge of the said sum of

five hundred pounds Provided that the said Edward Coates shall not have any right to the

said sum of five hundred pounds or any other payment under this :clause unless he shall ,

be in my employ as a manager at my death.

Excerpt from the will of Alfred Heaver – 2nd March 1898 – setting out the remarkably cold terms for the continued employment of his initial business partner. This gives a valuable insight into Heaver’s unsentimental thought processes. Edward Coates is to be supported by his Trustees but in an estate where the portions to the descendants were £57,000 to leave £500 is far from overtly generous.

Alfred Heaver’s Developing Housing Business

It is clear from a search of the Minutes of Proceeding of the Metropolitan Board of Works that Alfred Heaver became very active from 1879. We have searched the minutes and collated the search results here on a separate page.

We can also see from the maps and the extant building records that construction proceeded at quite a steady pace. There was no sense of streets being thrown up speculatively. Heaver, had learned from his earlier bankruptcy and developed a sound business model – build steadily with a substantial cash buyer to hand, sell the majority on completion to attain good cashflow and retain the profit element as houses.

The clear conclusion that can be made from all of this is that Heaver became a very adept businessman before his untimely death.

Heaver and The Pru

Contrary to a lot of stories, Alfred Heaver, obtained most of his later finance from The Prudential Assurance Company Limited [The Pru]. There is absolutely no mystery about this at all as it is stated in both the tithe books as well as a number of extant deeds.

You can read the 1st October 1897 Eight Deed between Alfred Heaver & The Prudential Assurance Company Limited [click link for full PDF].

Deed of Family Arrangement

An extensive bound and printed deed of family arrangement was drawn up dividing the very substantial remaining property holdings between George Heaver and Alfred Heaver [the younger] dated 20th March, 1893. Even producing such a deed would have been a substantial investment. However, given the size and scale of Alfred Heaver’s holdings it made perfect sense to print the pages listing out the properties, otherwise a longhand version would have been massive and hard to consult or copy.

The deed lists out holdings in Fulham, Wandsworth & Clapham.

We are fortunate that a full copy survives as it sheds a very clear light on Alfred Heaver’s business style and execution.

The Deed of Arrangement [click link for full PDF] is a substantial document which contains a full schedule of properties as well as coloured plans.

It is very clear from the 5th Schedule Plan [below] that the best and largest houses, on The Heaver Estate, Balham, had been retained as family assets. Presumably, as these would give the best yields.

A sample page [below] from Deed of Agreement dated 20th March, 1893 listing out the houses that had been retained by Alfred Heaver and how they were to be divided between his sons George Heaver and Alfred Heaver Junior.

Why do some of the houses on the Heaver Estate have historical basements?

One of the things that is really obvious from this 1937 oblique aerial photograph is the varying topography of the lands.

This leads in the middle section of most of the roads such as Huron, Drakefield and Louisville to the formation of historical basements with front access steps. Usually in Edwardian or Victorian building practice the addition of a basement is a pure reflection of the historical ground levels. The road levels were dictated by the mains drainage which was gravity drained so no dips were allowed. Given that carting fill materials around, such as soil, ballast or sand was very hard and expensive with a horse and cart a different solution was often arrived at: a basement. These historical basement excavations, with the spoil used to make up the road levels, should not be confused with the coal cellars that were essential at the time for housing developments at this level.

This makes the Heaver Estate a very natural place for basement conversions and basement excavations.

Aerial Photography

Pre war photo of the Heaver Estate: a 1937 oblique shot looking from Tooting Common towards Balham Station.

Post war, 1947 RAF image, showing the areas of bombed out houses